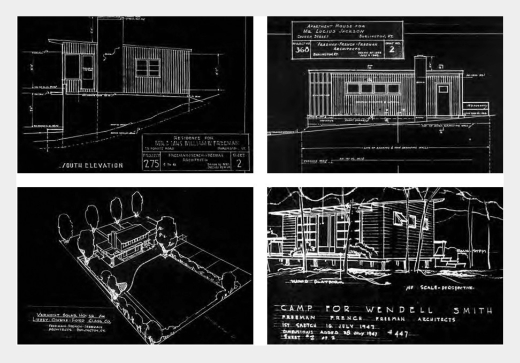

The Gutterson Fieldhouse at the University of Vermont. St. Mark Catholic Parish on North Avenue. The Given Medical Building of the UVM College of Medicine. The NBT Bank on Bank Street. The Sustainability Academy at Lawrence Barnes. Ohavi Zedek Synagogue. Rice Memorial High School. What do all these greater Burlington buildings from the 1940s, '50s and '60s have in common? All of them — and hundreds more around Vermont — were designed by one architect: Ruth Reynolds Freeman. [Figure 1]

It's unusual for any one architect to shape the built environment of a town and state to such a degree, but particularly unusual for a woman, let alone one of Freeman's era. A pioneer in a male field, Freeman was the second woman to graduate from Cornell University's architecture program, in 1936. The following year, she and her husband, fellow Cornell alum William Freeman, joined John French, a graduate of the Wentworth Institute in Boston, in founding Freeman French Freeman in Burlington. FFF was the first architectural firm in Vermont to open its doors, making Ruth Freeman Vermont's first female architect.

Technically, all the aforementioned buildings should be attributed to the firm. But Ruth Freeman was its lead designer throughout her career. As a 1949 Progressive Architecture article notes, "Mrs. Freeman is responsible for most of the design and makes most of the presentation drawings." French, an engineering expert, was said to handle "drafting room supervision"; William Freeman primarily interfaced with clients and acted as "design critic."

The architect William Wiese, who joined FFF in the early 1950s and stayed for 45 years, recalled in a 1990 interview that he was still visiting Freeman's bedside to consult on designs in 1969, the year she died of breast cancer.

"There was never any doubt who was in charge of design while she was alive," Wiese remarked. The facts of Freeman's career bear this out. On receiving her Cornell BA, the Brainardsville, N.Y.-born architect placed second in the American Institute of Architects' competition for "general excellence" in a bachelor's program.

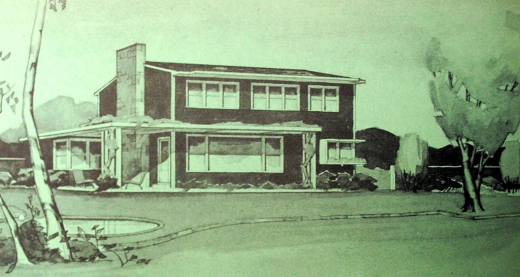

In 1946, Freeman was chosen to design a solar house for a book project dreamed up by Libbey-Owens-Ford, the first glass company to manufacture insulating double-glazed windows. The book was called Your Solar House, and its editors commissioned designs from one architect in each state. Freeman's appeared alongside those of iconic modern architects Louis Kahn, Edward Durell Stone and Pietro Belluschi. [Figure 2]