Rocky Mountain Modern is part of the Docomomo US Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country, without leaving your home. In honor of our newest Docomomo US chapter, this edition introduces you to some of Colorado's iconic modern sites.

Rocky Mountain Modern Part One

The U.S. Air Force Academy

by Robert Nauman

On July 23, 1954, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) was awarded the contract to design and construct the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. The site itself was chosen from over 580 submissions by a Site Selection Committee that included Reserve Brigadier General Charles A. Lindberg, while over 300 architectural firms applied for the commission – one of the largest government construction projects of the Cold War era. Constructed during Eisenhower’s presidency, the Air Force Academy was intended to complement the established military academies at West Point and Annapolis.(1)

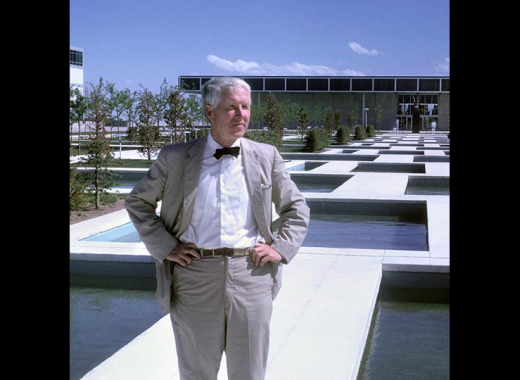

Upon receiving the commission, SOM assigned 34-year-old Walter Netsch, who had graduated from MIT in 1943 and joined the firm in 1947, as the resident architect of the project. Netsch had earlier worked on SOM projects that included the Manhattan Project town of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, military installations in Okinawa, Japan, and the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey. The Monterey project included a complex of buildings for 800 students, designed using a modernist architectural vocabulary. Netsch was inspired not only by European modernism (especially the work of Gropius and Le Corbusier) during his education, but also by the work of Alvar Aalto and of course, working out of SOM’s Chicago office, by American “Chicago School” architects that included Jenney, Sullivan, and Wright.(2)

Working with Netsch on the Air Force Academy project was a design advisory board appointed by the Secretary of the Air Force that included Eero Saarinen, Wallace Harrison, and Welton Becket. Emphasizing issues of economy, efficiency, and practicality, SOM adopted an International Style modernist vocabulary for the Academy design – a vocabulary they had employed earlier in the 1950’s with projects such as Lever House and the Manufacturers’ Trust Bank.(3)

For the initial exhibition of the design at the Colorado Spring Fine Arts Museum in May 1955, the firm hired renowned exhibition designed and former Bauhaus teacher Herbert Bayer to oversee the exhibition. The extravagant exhibition, which cost $100,000 at the time, used photographic murals of Ansel Adams and William Garnett to form the backdrop for models of the various Academy areas, while Ezra Stoller was hired to take images of the models that were subsequently released to the press. Drawing on the striking photographs of Colorado’s Rampart Range to link the modernist design to its site, the exhibition was intended to persuade the members of Congress in attendance to fund SOM’s design.(4)

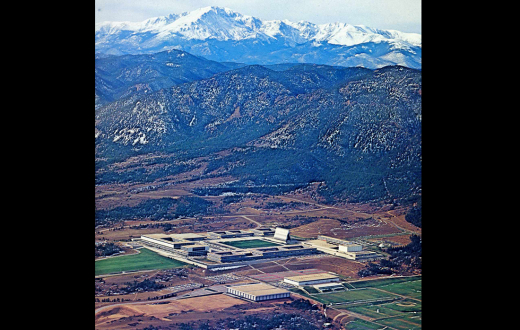

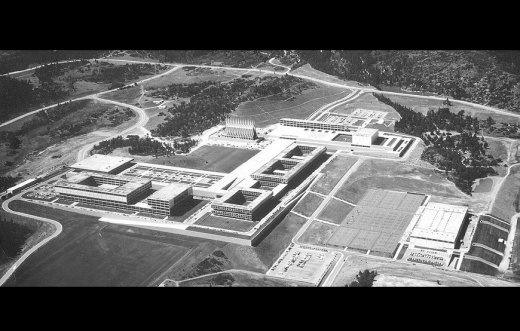

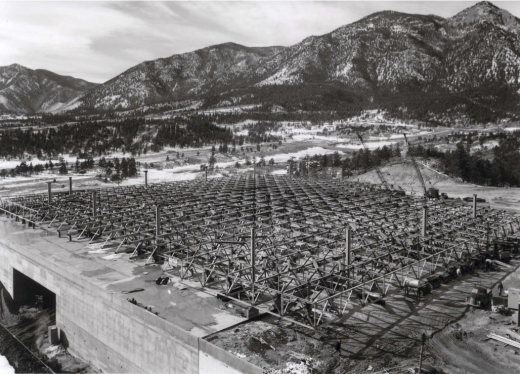

Netsch’s design concept for the Academy was to locate the Cadet Area on Lehmann Mesa, evoking the Greek Acropolis both in terms of siting and also in terms of the abstracted classical design of the cadet buildings.(5) The residential communities, on the other hand, would be located in Pine Valley and Douglas Valley. Netsch’s intent was that the residents of these areas would be forced to interact with the spectacular location beneath Pike’s Peak during their daily activities as they drove to other areas on the Academy site. The Cadet area itself would be designed on a 7’ grid that would meet functional demands while interfacing with the site itself. The grid design was inspired in abstract fashion by both Japanese tatami proportions, which Netsch had experienced when he worked in Japan, and by modernist modular design approaches employed by architects such as Le Corbusier. There was also a more humanistic reason for choosing the 7’ grid. Due to an extremely tight schedule to get the Academy open and functioning, Netsch needed to find an Academy-specific module that could be used as the governing grid for all Academy development. The Air Force made a commitment never to have a class graduate from the Academy that was not from the permanent site, which meant that all facilities necessary to support the Class of 1959 had to be operational in 1958. To find the ‘right’ module, Netsch asked himself what the most repetitive item was that they were going to design. That was the dorm rooms. The most important thing in the dorm room was the bed. An American bed is approximately 7’ from the toe of the bed to the wall. Hence the 7’ dimension.(6) The geometric design would, as Netsch stated, “. . . contrast with nature’s more complex character.”