Historical context for modern sites in South Dakota is still in its fledgling stages. The three articles in this regional spotlight were contributed by staff members of the South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). Our office knows that the Modern period will be an increasing part of our work to evaluate historic significance of built resources and provide preservation guidance and resources to property owners and local governments. Having wide gaps in the state’s architectural history will do a disservice to modernist styles and architectural forms, and to the work of late-20th century architects. We have been expanding our architect files and have contracted for contextual histories of postwar architecture and of single-family housing from 1950 to 1975, but there is a lot more yet to do. This is starting to filter into local communities, with historic preservation boards/commissions in Sioux Falls and Rapid City recently working on survey and planning projects that compiled information on the midcentury period. Recognition of modern resources within the general population of South Dakota is still a hill to climb. We also assume that, broadly speaking for those outside the state, awareness of this history is likely negligible. Writing this set of spotlight articles has served as a way for our staff to expand their knowledge about Modernism, and it is our humble way to introduce South Dakota to the wider Modern Movement audience.

Get to know South Dakota Modern Part One

Modernism in the Black Hills

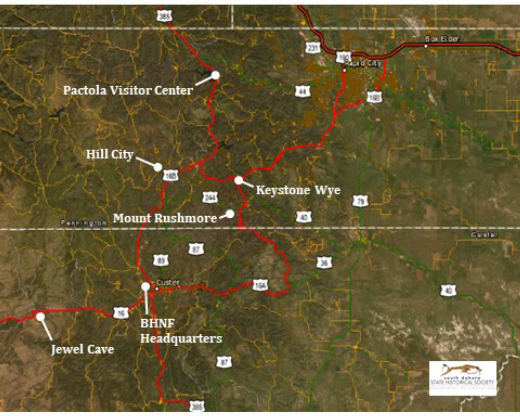

The Black Hills of South Dakota have long been known for their picturesque views, monumental sculptures, national historic districts, and abundant outdoor activities. While many of these features draw numerous tourists to the Black Hills region, the modern architecture hidden within the hills is testament to the rise of leisure and outdoor recreation in the United States in the mid-20th century. More and more tourists were traveling by automobile, which were more affordable and common. This brought an increase in the use of public resources like road networks and the national and state park systems.

With the rapid increase in travel and leisure, government agencies and towns in established tourist areas raced to build and update attractions and accommodations. To help expand public resources for recreation and tourism, the federal government set up several programs including the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956; the creation of the Recreation Advisory Council in 1962, an interagency group that in 1964 promoted the funding of scenic roads and parkways; and the founding of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in 1962. One of the key federal acts from this era that influenced recreational architecture throughout federal, state, and local levels was the National Park Service’s Mission 66.

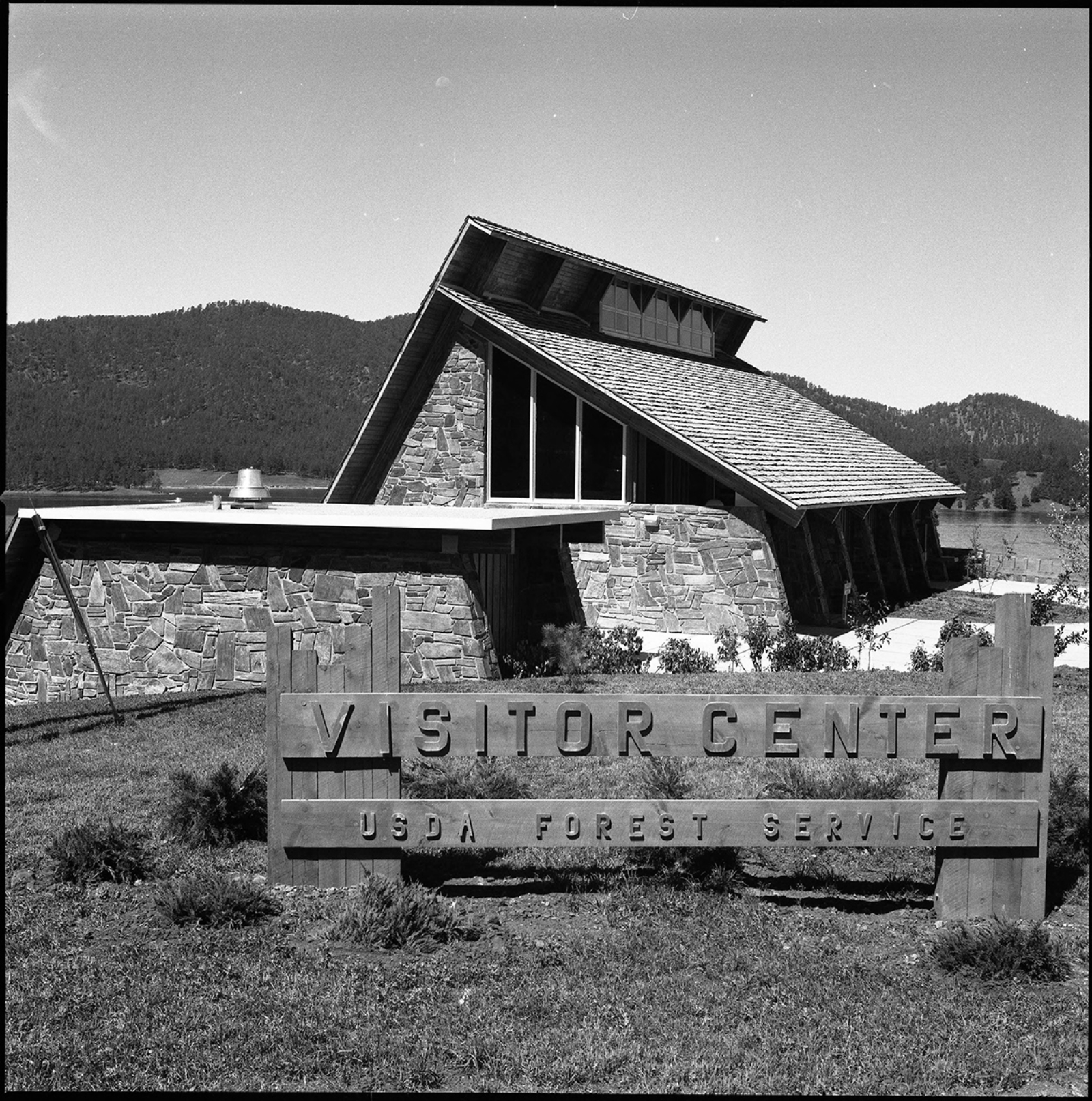

After World War II, the National Park system lacked the attention and funding needed to keep up with the increasing numbers and demands of visitors. In 1956, by framing their funding needs into a mission style request, the National Park Service was able to secure Congressional appropriations for the park system that would last through 1966. The funding from this program went into park improvements such as repairing roads and building new facilitates for visitors and staff. During this construction era, the National Park Service adopted a new architectural style that came to be called the Park Service Modern style. This style retained the earlier rustic-style approaches of blending new construction with the surrounding setting, but also adopted plain and streamlined aesthetics to keep the attention on the natural beauty of the buildings’ surroundings. Shortly after the initial success of Mission 66, this architectural concept was adopted on state and local levels.

The Black Hills National Forest and Custer State Park had been established in 1897, Wind Cave National Park in 1903, and Jewel Cave National Monument in 1908, with Needles Highway and Mount Rushmore joining them in the 1920s. In the 1930s, New Deal era improvements through the Civilian Conservation Corps and other programs injected a lot of new tourist facilities. On this solid foundation, increasing tourist demands of the postwar era greatly affected the Black Hills. Custer State Park recorded having over one million visitors in 1961. Although some architectural works, like the Mission 66 visitor center at Mount Rushmore, are already lost, many of the structures built during this time are still present for the public to visit and view.