The town of Norwich, Vermont has a deep and rich developmental history dating back to the mid-18th century. As the town grew over the next century, its residents built houses in the Georgian, Federal, and Greek Revival styles. There was little new construction in Norwich during the period of population loss in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and as a result there are few examples of Victorian, Arts and Crafts, Art Deco, or bungalow-style buildings in the town. Between 1944 and 1974, however, development began again, and low-slung homes of the style now known as Mid-Century Modern were built on the hillsides in Norwich. Often architect-designed, these homes featured the abundant windows and open interiors that were seen by some visionaries as solutions to the needs of modern, postwar American family life. The circle of architects, artists, scholars, and doctors who settled in Norwich during and after World War II were drawn to the area for its proximity to Dartmouth College, located just across the Connecticut River in Hanover, New Hampshire. These progressive new residents had a strong influence on the community and its landscape, bringing an infusion of modernism and internationalism into an otherwise traditional setting. Their interest in new technologies and building materials have left a legacy for Norwich today.

The story actually begins in the 1930s, when the Dartmouth College Art Department established its Artist-in-Residence program to bring artists to campus for short- and long-term residencies. The program brought architects, artists, designers, painters, and other thinkers of the period, becoming the locus of an exciting ferment of modernist ideas. These included Lewis Mumford, Walter Gropius, Alvar Aalto, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

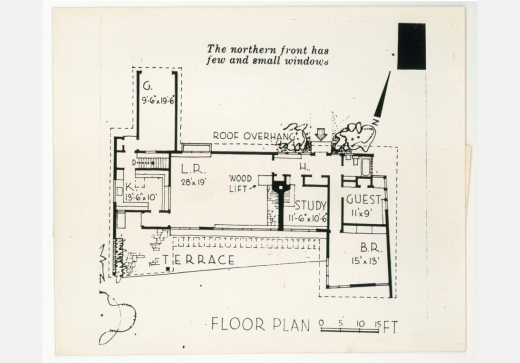

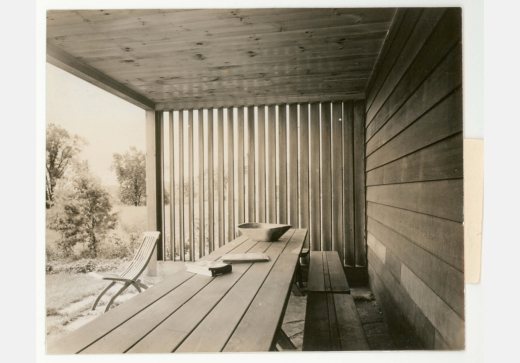

As the Nazis came to power, Lewis Mumford found funding through the Rockefeller Foundation Refugee Scholar Program to help modernist architect Walter Curt Behrendt and his wife Lydia leave Germany and come to Dartmouth. In 1942 Behrendt designed his own house in Norwich, which was featured in the magazine Pencil Points. [Figures 1 & 1A] The design was for a house that a Dartmouth professor could afford on a half-acre lot with sweeping valley views, one that could survive erratic New England weather and offer space for his wife, who was a professional musician. This first modernist house in Norwich merged the inside and outside and combined spaces within so functions could flow. [Figure 1C] The kitchen was connected to the combined dining-living room and included a pass-through window to a dining porch. [Figure 1B] A roof projection over the windows in the south wall was designed for passive solar. Oral histories tell of a salon atmosphere filled with discussions and music.

Modern Architecture Comes to Norwich, Vermont

Author

Sarah Rooker

Affiliation

Director, Norwich Historical Society, Norwich, VT

Tags

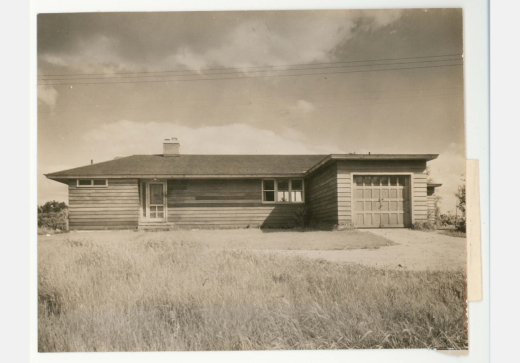

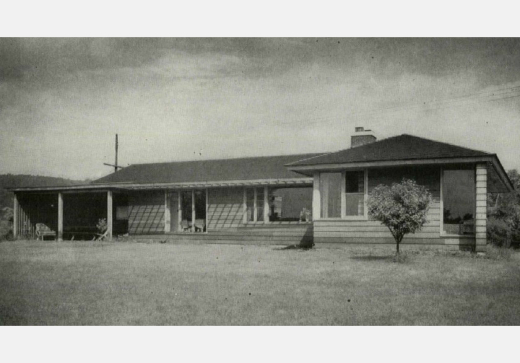

Architects Ted and Margaret (Peg) Hunter moved to Hanover, NH, in 1945, the same year that Behrendt died. Both were students of Walter Gropius at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and shared Gropius’ philosophy that the landscape and climate rather than architectural tradition should influence building design. In the 1953 issue of New Hampshire Architect, the Hunters wrote: “The demands of the New Hampshire region were met in careful planning for the trying climate, in large glass areas oriented south for natural heating, in liberal use of thermal insulation, and in use of flat or low-pitched roofs to hold snow and gain ‘free’ insulation value. In these practical and aesthetic effects of climate on design, the architects believe, lies true regional expression.”

Breaking with the tradition of building on flat land bordering town greens, the Hunters started building in the hills around Hanover and Norwich. The uphill slopes had previously been impassable in winter, but new cars and new road-building technology opened them to year-round living and rooms with an expansive view.

The Hunters’ house for Dartmouth professor Wentworth Eldredge exemplifies their principles. Published in Architectural Record, it was designed to convey that it was “a setting for sophisticated people who entertained handsomely, in a rural setting.”

A heavy chimney wall, the dominant vertical on the exterior, separated the servant’s quarters from the family living areas. A flat roof and deep eaves created horizontal juxtaposition and that “free insulation value” provided by snow. A carport, a ubiquitous part of the Hunter design, protected the car from snow. The Hunters went on to build 5 houses in Norwich. In one home, Peg Hunter chose the furniture (some by Jens Risom and Herman Miller), fabrics, and all interior accessories, down to the last piece of tableware.

When MIT professor Walter Stockmayer learned he was to move to Dartmouth, his wife Sylvia wrote to her friend Lucille Zimmerman for advice on finding an architect, as she loved the Zimmerman’s Frank Lloyd Wright home in Manchester, NH. Mrs. Zimmerman referred her to Allan Gelbin, a former apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright. The resulting home designed by Gelbin followed his Wrightian principles of conveying a sense of shelter and privacy with a relationship between the building and site and interior spaces flowing freely. [Figure 3 – photo by Robert Umenhofer] The house rests on a terracotta-red concrete slab, heated by hot water circulated in copper coils laid within the slab. Brick and yellow cypress wood were used for both interior and exterior finishes, and glass walls with clerestory windows above flood the room with southern light. [Figures 3a and 3b – photos by Robert Umenhofer] Gelbin wrote, “It is a home that has always been in harmony with nature—never an imposition upon it.” The three additional houses Gelbin built in Norwich also enjoy generous views, use passive solar, and nestle into the landscape. [Figure 4]

These modernist homes contribute to the richness of Norwich’s history and landscape. They reveal fundamental shifts in American life toward privacy and a car culture. Their architects pioneered approaches to passive solar design, the use of new technologies, and new orientation to the landscape, paving the way for today’s solar initiatives, land conservation practices, and innovative design.

Notes

In recognition of the historic and architectural significance of these modernist houses, Norwich has been systematically researching, documenting, and listing them in the National Register of Historic Places. These efforts have been led by the Norwich Historic Preservation Commission, which since 2010 has managed the town’s Certified Local Government (CLG) program. With the financial support of multiple CLG grants the town has been able to hire professional architectural historians to research and write National Register nominations for the following properties:

- Norwich Midcentury Modern Historic District (2018)

- Walter & Sylvia Stockmayer House (2020)

- Wentworth & Diana Eldredge House (2021)

In addition, a National Register Multiple Property Listing for “Mid-Century Modern Residential Architecture in Norwich, Vermont” has been written to facilitate the nomination of more modernist houses in Norwich to the National Register in the future.

The Norwich Historical Society is an important partner in these projects, mounting exhibitions about modernism in Norwich and using the National Register nominations as a springboard for public lectures and walking tours throughout the community. These have proven to be very popular and indicate that the general public wants to know more about these “modern” historic buildings.

About the Author

Sarah Rooker is Director of Norwich Historical Society. She studied architectural history at The College of William and Mary and has a Masters in History from the University of New Hampshire. She is co-editor of A Noble and Dignified Stream: The Piscataqua Region in the Colonial Revival, 1860-1930.

Green Mountain Modern is part of the Docomomo US Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home. Previous spotlights include Chicago, Mississippi, Midland, MI, Houston, Las Vegas, Colorado, Kansas, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, and South Dakota. Have a region you'd like to see highlighted? Submit an article.

If you are enjoying this series, consider supporting Docomomo US as a member or make a donation so we can continue to bring you quality content and programming focused on modernism.