Our society learns to appreciate past architectural styles in waves, and landmark buildings attract attention earlier than other types of structures. In the mid-20th century, the Catholic Church in South Dakota invested in a handful of worship spaces that stand out in the top tier of Modernist ecclesiastical design for the state, making them an excellent introduction to architecture of the Modern movement in South Dakota.

The two covered in depth in this article are Blue Cloud Abbey in Marvin, designed in 1950 by Chicago architect Edo J. Belli, and the Cathedral of Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Rapid City, designed in 1961 by local architect Adrian L. Forrette.

Additional sites worth mentioning include:

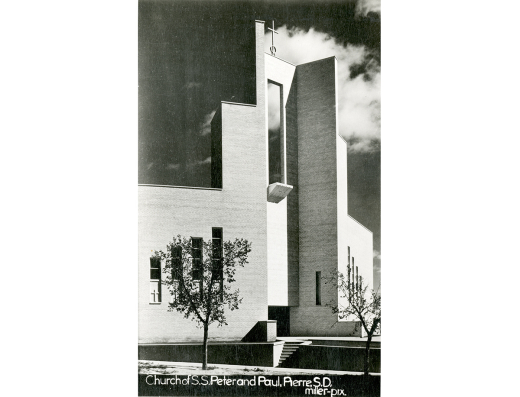

Sts. Peter and Paul in Pierre, built in 1940 from a design by Barry Byrne (Chicago); St. Mary’s in Sioux Falls, built in 1958 from a design by Harold Spitznagel (Sioux Falls SD);

Modernist Standouts among the Catholic Churches in South Dakota

Author

Liz Almlie

Affiliation

South Dakota State Historical Society

Tags

the Holy Cross chapel at St. Martin’s Monastery in Rapid City, designed c.1961 by Mark F. Pfaller (Milwaukee WI);

Christ the King church in Webster, designed in 1966 by Ralph Koch (Sioux Falls) with a circular sanctuary to evoke biblical tents;

St. Ann’s in Humboldt, a spiral design by Ward Whitwam (Sioux Falls) in 1969; and Holy Name in Watertown, a fan-shaped layout influenced by the Second Vatican Council and designed in 1971 by Steele and Peterson of Spitznagel Partners (Sioux Falls).

Other denominations are also represented in the list of ecclesiastical Modern examples in South Dakota, particularly larger Lutheran churches designed by the Spitznagel firm like those for Grace Lutheran in Sisseton, Our Savior’s in Sioux Falls, and Trinity Lutheran in Yankton.

Blue Cloud Abbey (Abbey of the Hills), Marvin

The St. Meinrad Archabbey in Indiana (Order of St. Benedict) established the Blue Cloud Abbey in the Coteau Hills southeast of Marvin, South Dakota, in June 1950—“traditionally, as in early Chrisendom, the monastery is built on a hill, signifying an open expression of closeness to God.”(1) In 1952, it was dedicated as a priory, and in March 1954, was made fully autonomous from St. Meinrad. The abbey was named Blue Cloud for Mahpiyato / Blue Cloud, a leader of the Ihanktonwan Dakota in southern South Dakota. He was a prominent convert to Catholicism early in the history of the Church’s work in Dakota Territory. A daughter of Mahpiyato attended the abbey’s dedication ceremony in 1952. The priests and brothers resident at Blue Cloud Abbey were tasked primarily with continuing St. Meinrad’s missionary work with American Indian tribes in North and South Dakota, including the training of missionaries and catechists. The monks also worked at churches near the abbey, studied in the abbey’s libraries, quilted, ran a farm and greenhouse, made bread, and demonstrated hospitality—eventually the facility was also used as a Catholic retreat center. At its height, forty monks lived at the abbey. In May 2012, the remaining fourteen monks of advancing years voted to close the abbey. In 2013, several local families formed a non-profit organization to run the complex and its core eighty-five acres, renaming it Abbey of the Hills Inn and Retreat Center.

The abbey had also had a large collection of material culture and photographs at their American Indian Culture Research Center, which Father Stanislaus Maudlin established in 1967. Maudlin had worked for decades on various Dakota mission stations. Initially meant to support ecclesiastical training, the Research Center also became an archive for cultural preservation, family histories, and more. When the abbey later closed, the collection was deposited with the Center for Western Studies in Sioux Falls. In 1968, Brother Benet Tvetden also turned the abbey’s fundraiser newsletter, the Blue Cloud Quarterly, into a literature publication that for twenty years published contemporary poems by American Indians from across the country. The first issue printed multiple poems/lyrics by Buffy Sainte-Marie, with photograph images of the Wounded Knee massacre, Apache prisoners, and Robert Kennedy’s visit to the Oglala Lakota on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Later issues also included images of original work by artists like Paul War Cloud. The Quarterly quietly became a critical venue for emerging poets and creative voices in the period of the “Native American Renaissance” in literature and the arts. The published works documented and confronted readers with the societal and cultural realities being experienced by native people, "a strong theme of conflict with dominant Anglo culture ran throughout. The construction of a sense of self in contrast to the perceptions of white America.”(2) The Quarterly’s change of focus paralleled evolutions in Catholic policy towards mission work. For instance, Blue Cloud Abbey decided in 1969-1970 to turn over management of their mission schools to the respective tribes.

The abbey complex was designed by Chicago architect Edo J. Belli. Edo J. Belli (1918-2003) had attended courses at Armour Institute of Technology while working for Holsman & Holsman in his early career. Starting his own firm with his brother Anthony after World War II, Belli & Belli often worked for the Catholic Church and the Benedictines. While they were planning a design for a monastery at Aurora, Illinois, Edo and Anthony stayed for a few days at St. Meinrad Archabbey to experience the life of a monk—they received this South Dakota commission from that visit. They later also did a motherhouse at Nauvoo, Illinois, for the Sisters of St. Benedict.

The firm Herges, Kirchgasler and Associates of Aberdeen, South Dakota, also participated in the last stages of construction. Clarence Herges (1919-2005) and John Kirchgasler (1923-1984) formed their partnership in 1957. They had several projects for the Catholic Church, as well as other churches, commercial companies, public libraries, and the state college in Aberdeen.

In 1951, as construction got started at Blue Cloud, the first ten monks from St. Meinrad lived in a old farmstead, using a renovated chicken house for a chapel. For the actual construction, St. Meinrad sent workmen, the monks did a lot of the work, and they occasionally had visitors from the missions to work on the buildings. The first year’s work included the basement and first floor of the first wing, as well as laying in sewage lines and digging a well. Mission students on the reservations often did vocational training and participated in building projects on their respective missions, and at least on one occasion, male students from Stephan on the Crow Creek Reservation visited Blue Cloud to assist building workers in pouring concrete. By March 1953, the Sioux Falls newspaper reported that the first wing was largely complete and “today they have a self-sustaining farm, [with] their own butchers, cobblers, carpenters, mechanics, and even a bakery.”(3) The full complex included the church, chapel, offices, kitchen and two dining halls, residential wings with large activity and library rooms, a greenhouse, a machine shop and garage, orchard and gardens, ponds, and cemetery. The last portion of the complex to be completed, the abbey church, had its consecration ceremony in October 1967. The event also included an organ recital and a wacipi (powwow).

The abbey is expansive and almost entirely stone or stone clad. The Indiana limestone on the exterior and interior walls, from the quarry at St. Meinrad, is warm and glowing and intricate. Multi-colored granite panels comprise a mural of Christ on the exterior wall of the church’s east elevation. Granite quarrying had long been a significant local industry in the area. The low-pitch gabled ceiling and rear wall of the sanctuary is California redwood paneling, and the flooring is terrazzo stone tile. Daprato Studios of Chicago worked on the “marble altars, stained glass windows and other sacred furnishings.”(4)

Along the top of the south wall is an immense, elaborate stained glass window depicting a biblical chronology in a Modern style. The first panels show figures and symbols from the Old Testament, but the rest largely follow the story of Christ from the Annunciation to the Resurrection. The window is in a frame of twelve panels each divided into three square parts, with elements of the design carrying across the panels, and the glass has a large quantity of blue and turquoise, with yellow, red, green, purple, brown, and other detail colors. Side altars feature large panels of stained glass depicting St. Benedict, St. Scholastica, and the Sisters of St. Benedict in scenes of mission and education work. Additional stained glass in geometric patterns of light-colored blues, purples, yellows, and browns is found along the north entrance aisle, at the clerestory on the west part of the south wall, and on the sides of the north side altar.

Cathedral of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, Rapid City

In 1960, the number of Catholics in the Rapid City diocese reached a record high. With the postwar growth of Ellsworth Air Force Base and the tourist industry, the overall population in the Rapid City area had grown tremendously. In 1948, William T. McCarty became bishop in Rapid City and initiated the process for a new cathedral. In January 1959, he sent out the announcement with building plans to be read by all the parishes, and that April, began a diocese-wide funding campaign. McCarty hired Adrian L. Forrette, a partner in the Rapid City architectural firm Ewing & Forrette, to design the complex, which included a primary sanctuary, chapel, baptistery wing, offices, social hall (basement), and rectory. Structural engineer Ray L. Roby of Mitchell, South Dakota, also worked on the building design, and the local company Brezina Construction were general contractors. The diocese held ground-breaking ceremonies for the Cathedral of Our Lady of Perpetual Help in the winter of 1960, and it held the first mass on the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary on August 15, 1962. The formal dedication was held May 7, 1963, with Archbishop Egidio Vagnozzi, Apostolic Delegate to the United States.

Adrian L. Forrette was born in September 1893 in Adrian, Minnesota and graduated from Dunwoody College in Minneapolis. After overseas service in World War I with the 306th Infantry, he returned to South Dakota in 1922. Ewing & Forrette was established in Rapid City in 1939 and was in practice until Forrette’s retirement for health reasons in about 1963. Forrette sold his interest to James Ewing Jr. who joined his father in the practice. Forrette passed away in Rapid City in March 1968. His and his firm’s other work included World War II-era housing developments in Rapid City, a building for the state soldiers’ home in Hot Springs, and in Rapid City: the Gambles department store, facilities for the South Dakota School of Mines, and the municipal building.

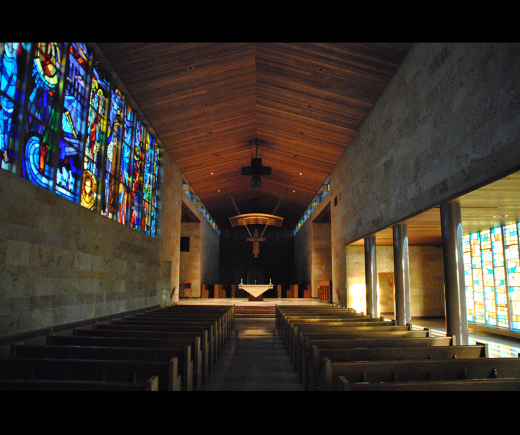

The Cathedral’s construction included reinforced concrete, Mankato limestone walls, and Indiana limestone trim. Designed just prior to the Second Vatican Council, the cathedral’s primary sanctuary (235 ft. long) is laid out in a quite traditional basilica plan, with two columns of pews either side of a central aisle with arched square columns along each outside aisle of the nave. There is a gallery and organ at the rear (east) end, and the altar and chancel are at the west end. The sanctuary’s ceiling is a barrel vault with cylindrical pendant lights hanging in four rows. There is green marble that trims the sanctuary in clean lines and veneers the base walls in a book-matched layout. Green, white, and black marble flooring was set in large geometric patterns throughout the sanctuary.

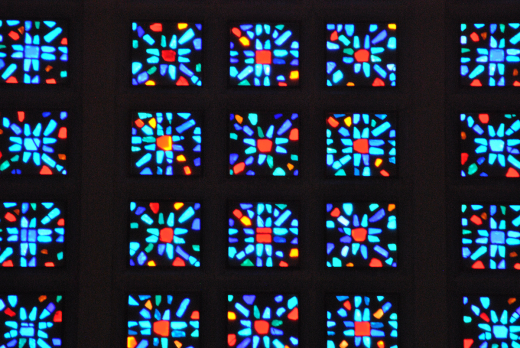

Stained glass around the building is found in a beautiful variety. Seven columns of square tiles of primary-colored faceted glass in a starburst pattern, set in concrete bedding in a grid frame of limestone, makes up a large window on the east façade, at the rear of the sanctuary. Leaded stained-glass windows run along the north and south walls of the sanctuary. They depict biblical scenes and church figures amid swirling geometric backgrounds. Off the south end of the narthex, nearly the full height of the walls leading to and surrounding the circular baptistery (18-ft. diameter) are comprised of leaded stained glass window panels in a variety of solid blue, green, and red hues. At the central part of the Baptistery, a panel of glass in the baptistery depicts a dove and flame. The glass throughout the Baptistery provides incredible atmosphere to the space and reflects the symbolism of water and Spirit meeting in the sacrament of Baptism.

The Cathedral’s front steps are black and white Cold Spring granite. Above the main doors on the east façade and below a wave-shaped concrete canopy, are three mosaic tile panels depicting the saints Peter and Paul to either side of Christ. Panels of mosaic tile are found above entrances on the north side of the building as well, and blue and turquoise mosaic tile faces exterior walls of the baptistery in panels above the windows, set between its projecting concrete ribs. Atop the baptistery is mounted a sculpture of Christ, in an elongated modern style.

Notes

- Argus-Leader (Sioux Falls, SD), March 22, 1953

- Yardy, “A Labor of Love,” 34

- Argus-Leader (Sioux Falls, SD), March 22, 1953

- Argus-Leader (Sioux Falls, SD), October 11, 1967

Bibliography

Architect Files, South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office, Pierre.

Argus-Leader (Sioux Falls, SD), May 24, 1951-October 11, 1967.

“'Blue Cloud Reflections' Features Historical Images from the Blue Cloud Abbey American Indian Collection,” Center for Western Studies, Augustana University, Sioux Falls.

Callison, Jill. “A change in mission: After decades of outreach, activities center at monastery.” Argus Leader (Sioux Falls SD), September 13, 2004.

Dennis, Michelle L. “Cathedral of Our Lady of Perpetual Help,” SAH Archipedia, Society of Architectural Historians.

“Edo J. Belli: Biography and Oral History Summary,” Chicago Architects Oral History Project, Ryerson and Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago.

Galler, Robert. “Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School Tribal School.” Dissertation (3376), Western Michigan University, December 2000.

Gane, John F. American Architects Directory, 3rd Edition. New York: R.R. Bowker Co., 1970.

Koyl, George S., Ed. American Architects Directory. New York: R.R. Bowker Co., 1962.

“Our Story,” Abbey of the Hills Inn & Retreat Center.

Rapid City Journal (SD), March 16, 1968.

Solon, Sister Eleanor. We Walk by Faith: The Growth of the Catholic Faith in Western South Dakota. Strasbourg, France: Editions du Signe, 2002.

Yardy, Bethany A. “’A Labor of Love’: A Social and Literary History of the Blue Cloud Quarterly.” M.A. Thesis, University of Texas-Arlington, December 2014.

About the Author

Liz Almlie has worked for the South Dakota State Historical Society as a Historic Preservation Specialist since 2011. She received her B.A. in History at Augustana College (now University), Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in 2008, and her M.A. in Public History at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, in 2010.

Get to know South Dakota Modern is part of the Docomomo US Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home. Previous spotlights include Chicago, Mississippi, Midland, MI, Houston, Las Vegas, Colorado, Kansas, Pittsburgh, and Milwaukee. Have a region you'd like to see highlighted? Submit an article.

If you are enjoying this series, consider supporting Docomomo US as a member or make a donation so we can continue to bring you quality content and programming focused on modernism.