Pittsburgh's Modern Milieu Part Five

Troy West, Advocate Architect

Because Pittsburgh is a city replete with mid-century architectural gems, it should come as no surprise that it was also home to a number of fascinating personalities during the modern era. In conducting the research for the Imagining the Modern: Architecture and Urbanism of the Pittsburgh Renaissance exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art’s Heinz Architectural Center and the subsequent book, we made it a priority to meet some of the key players active during this critical time in Pittsburgh’s renewal. Among the most surprising discoveries was Troy West.(1) West was a surprise not just for his bold body of work, but for the participatory process by which they were created. His built legacy in Pittsburgh could be considered scant, but his influence on the city, the way architecture is taught, and the definition of a modernist architect is far more profound.

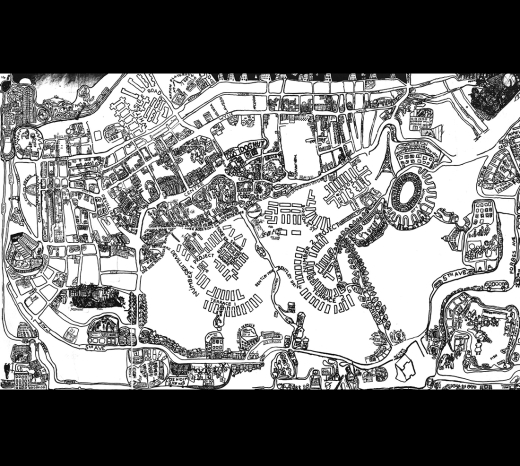

Troy West was born and raised in Pittsburgh. After graduating from Carnegie Tech he won the prestigious John Stewardson Memorial Fellowship in Architecture, traveled through Europe, and worked in Philadelphia with Louis Kahn and Oscar Stonorov. He returned to Pittsburgh in 1963, a tumultuous period in the city’s evolution, and was soon drawn to the vibrancy and culture of the Hill District, a largely Black neighborhood and home to the many jazz and poetry clubs that defined it. His advocacy-style teaching at his alma mater (now renamed Carnegie Mellon), and his collaborative practice presented a counter-narrative to the more top-down approaches that had earlier developed the Point and the Golden Triangle. His architecture embraced the expressive ideologies and forms of modernism, which, when coupled with his unwavering belief in architecture as a social project, became powerful forces in their own right to elevate the voices of those often ignored during the Renaissance.

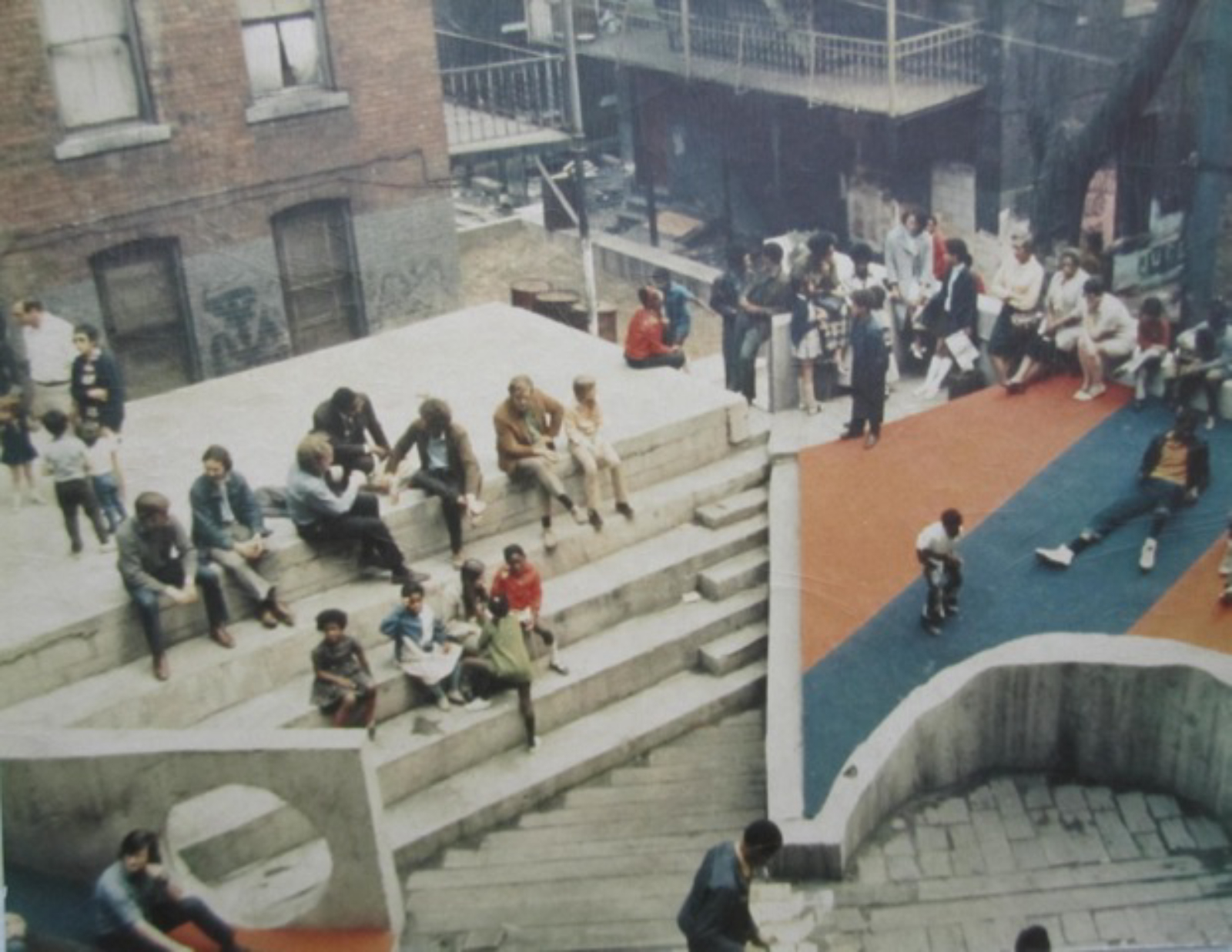

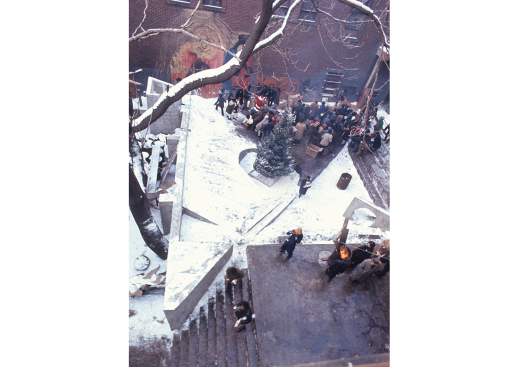

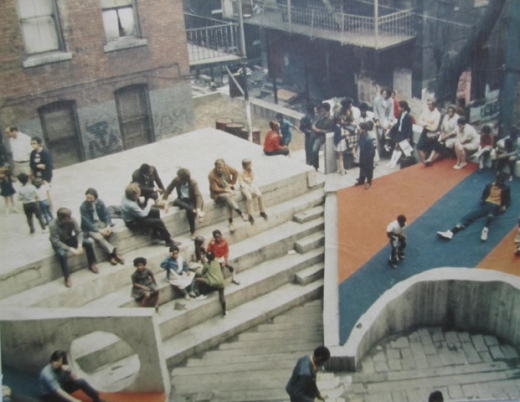

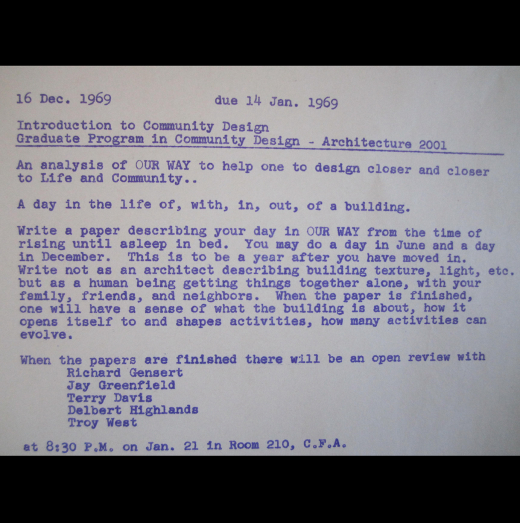

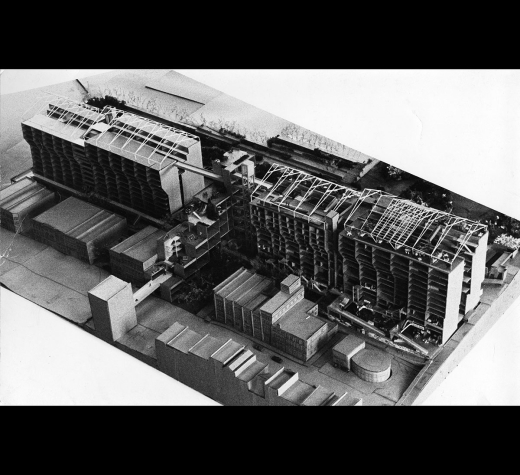

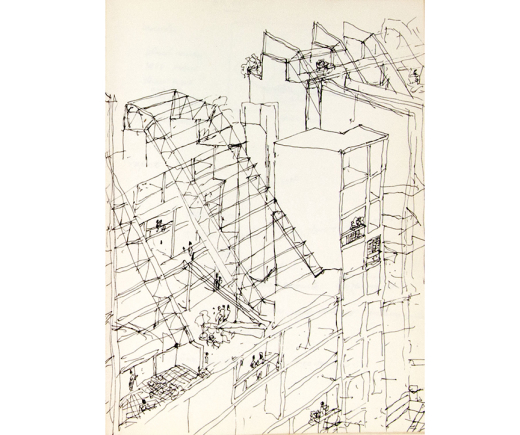

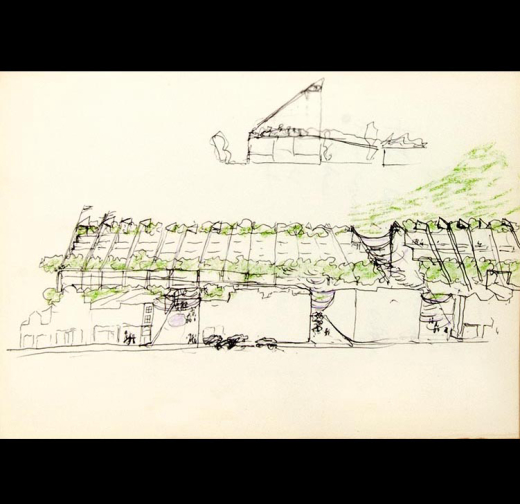

His first practice, Architecture 2001, was an unorthodox architecture firm; it included a psychologist and a lawyer as part of its original make-up, as well as a construction arm (Construction 2001 was led by a carpenter who had learned his trade in prison). Also significant, the practice was heavily invested in the Hill District, where it was headquartered. West’s focus on the district was manifested in a 1967 project, the Court of Ideas. Located on an empty lot with a significant grade change, a series of sloping geometric concrete plinths were asymmetrically arranged to shape a forum-like space while negotiating the parcel’s uneven terrain. Designed and built in collaboration with the community, the project played host to numerous events during the late 60s and early 70s: poetry readings, political rallies, Christmas parties (one with the theme: “Is Santa Clause really white?”), and musical concerts (including Art Blakey and Abbey Lincoln). Designers, architects and planners—Richard Saul Wurman, Aldo van Eyck, and Robert Goodman among them—all visited the Hill to witness this experiment in public space and interaction.