Identifying a project by its architect is a common occurrence; it's easy to associate a building with a single name. But a project is rarely the result of a singular vision. It's the result of a collaboration between the client, architects, engineers, and contractors for a specific site and defined problem. Among those unsung engineers is Sergio Acosta.

Engineering a Legacy: Sergio Acosta Remembered

Author

Thea Haver & Ethan Aronson

Affiliation

Modern Albuquerque

Tags

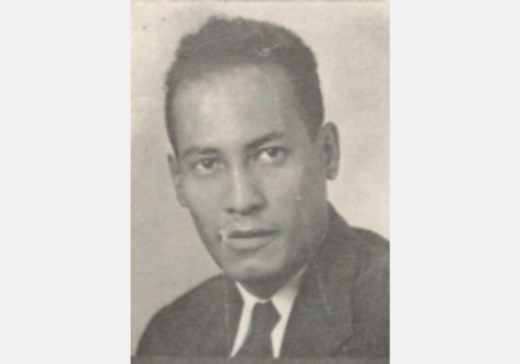

Born and raised in Panama, Sergio accepted a scholarship to the College of Engineering at the University of Texas, Austin in 1942. His daughter, Carmen, describes him as a 'math genius.' He saw math as the universal language and learned English during the course of his studies. Initially expecting to return to Panama City as an architect, Sergio instead found love. Though he and his family would briefly return to Panama, he quickly went back to Texas and on to Albuquerque in search of a better a climate and more multicultural community. Among his classmates in Texas were several aspiring architects: Max Flatow, Jason Moore, Van Dorn and Peggy Hooker among them. They would go from classmates to colleagues as Acosta joined the crowded ranks of Albuquerque's 1950s architects. He and his first wife Viva became members of the First Unitarian Church, for which he designed the first brick facility. Acosta quickly observed, however, that there were too many architects practicing in the city. In an effort to rise to the top, he furthered his schooling as an engineer and became licensed to practice as one.

As a structural engineer, Acosta floated between offices. He built a relationship with Fred Fricke, who he would later work on the UNM Fine Arts Center with. We believe that it was through Fricke that Acosta was drawn into such projects as the Albuquerque Civic Auditorium, which he took his children to visit while under construction (snapping photos of them for scale). Carmen recalls that he often visited sites to check on the construction. He was fully invested in the process of bringing a building to life.

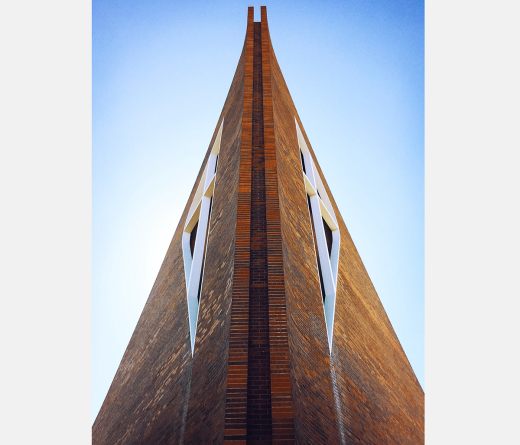

Acosta settled briefly in the Flatow, Moore, Bryan, and Fairburn office as their in-house structural engineer, and though Sergio would eventually leave to open his own office, one of the projects he was proudest of, the sweeping triangular St. Paul Lutheran Church, would reconnect them. Sergio embraced the challenge of ensuring the swoop would stay up. It's a project that would be heralded in the Arts section of the Albuquerque Journal as a 'dramatic new landmark for the city.' An article states that "the unusual beam design was shaped like a Y to support the sanctuary." Designer Jason Moore explained that Acosta used post-tensioning steel cables incorporated into the wooden beam and tightened with a wrench.

Carmen remembers every horizontal surface of their home being covered with plans. Acosta worked until midnight, lulling his two children to sleep with classical melodies on the radio. He was a patron of the arts, supporting local modernist painters such as Alice and Jack Garver and loaning works for gallery exhibitions. New Mexico's thriving arts community was one of the reasons he stayed. Acosta particularly enjoyed using his mathematical talent to calculate cantilevered elements. It's no surprise that his passions came together on the grand Santa Fe Opera, for which he collaborated with Earl Wood as a structural engineer. Architect Joe Mckinney fondly reflected that Sergio Acosta was one of the most gracious people he ever met; he could walk into a room and its personality changed for the better. Among others he worked with are the firms of Bridgers and Paxton, Britelle and Ginner, William Burk Jr., Art Dekker, Chambers and Campbell, and W.C. Kruger. Burk Jr.'s architect son, Bill Burk III, once joked that architects only needed to know a few numbers: a phone number belonging to a good structural engineer! Sergio Acosta was certainly that. Sergio's lasting legacy is not only the projects he was proudest of, but a work ethic that lives on in Carmen, her brother Clovis Acosta, and Sergio's grandchildren. His mantra was, "just keep working, it will get better." Carmen's brother declared very early that he would not be an architect, "no way, they're too poor!" But the family's appreciation of the arts has never waned. And, "we know how to build things," says Carmen.

Thank you to Carmen Acosta, her brother Clovis Acosta, and Joe Mckinney. Photographs of Sergio Acosta are from Carmen's personal collection and used with her permission.

This article first appeared in the November 2019 Modern Albuquerque newsletter.

About the Authors

Thea Haver co-founded Modern Albuquerque in 2018. She is the former Director of Education for the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History and continues to work with arts and cultural organizations in program development, project management, and marketing.

Ethan Aronson is co-founder and President of Modern Albuquerque. He studied history at Goucher College, including a semester of urban architecture at the University of Copenhagen. He is currently the Store Manager for the Maxwell Museum and a member of Historic Albuquerque Inc.'s Board of Directors.

Modern ABQ is part of the Docomomo US Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home. Previous spotlights include Chicago, Mississippi, Midland, MI, Houston, Las Vegas, Colorado, Kansas, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, South Dakota, and Green Mountain Modern. Have a region you'd like to see highlighted? Submit an article.

If you are enjoying this series, consider supporting Docomomo US as a member or make a donation so we can continue to bring you quality content and programming focused on modernism.