The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book Making Houston Modern: The Life and Architecture of Howard Barnstone, edited by Barrie Scardino Bradley, Stephen Fox, and Michelangelo Sabatino, published by the University of Texas Press, expected August 2020.

Making Houston Modern Part Two

Translating Mies: Barnstone and Houston Modernism

By Michelangelo Sabatino

During the English architectural critic Reyner Banham’s last visit to Houston, to write about the Menil Collection by Renzo Piano (with Richard Fitzgerald, 1986), he observed the interrelationships among three generations of architects--Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson, and Howard Barnstone--who all left an indelible mark on modern architecture in Houston:

Locally the echoes are of Mies van der Rohe, which may sound strange, but one should remember that, next to Chicago itself, Houston must be the most Miesian city in North America. Quite apart from Johnson’s works for the de Menil/St. Thomas connection, and Mies’s own extensions to the Museum of Fine Art, there is also the work of . . . Howard Barnstone himself, Anderson Todd, and a small host of their pupils, partners, and followers. Almost anywhere, it seems, in the rambling, unzoned dystopia that makes Houston an urbanist’s nightmare, one may stumble with relief on neat steel-framed structures with “made-at-IIT” written all over them, and as often as not the exposed I beams of their exteriors are painted white against their gray walls. . .(1)

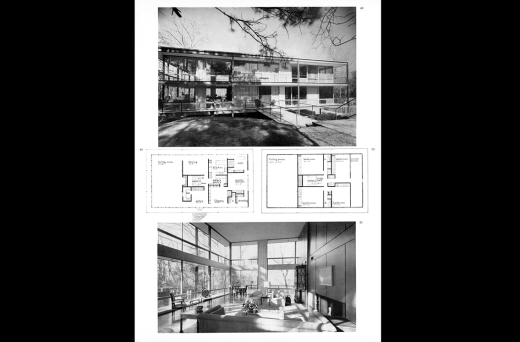

Mies’s Cullinan Hall (1958) and Brown Pavilion (1974), his two additions to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Philip Johnson’s Dominique and John de Menil House (1951) and University of St. Thomas campus (1957–1959); and Bolton & Barnstone’s Barbara and Alvin M. Owsley, Jr., House (1960) all represented a radical intervention in the cultural and domestic fabric of Houston, reflecting Miesian tectonics, materiality, and spatial clarity. The aura of cosmopolitan elegance and glamour associated with Miesian architecture that they emitted stood in contrast to the ordinary buildings of developers.(2) This intervention signaled shifts in postwar modern architecture as young, US-trained architects translated the experiments of European modernism to significantly different political and cultural frameworks.