The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book Making Houston Modern: The Life and Architecture of Howard Barnstone, edited by Barrie Scardino Bradley, Stephen Fox, and Michelangelo Sabatino, published by the University of Texas Press, expected August 2020.

Making Houston Modern Part Three

A Constructive Connection: Barnstone and the Menils

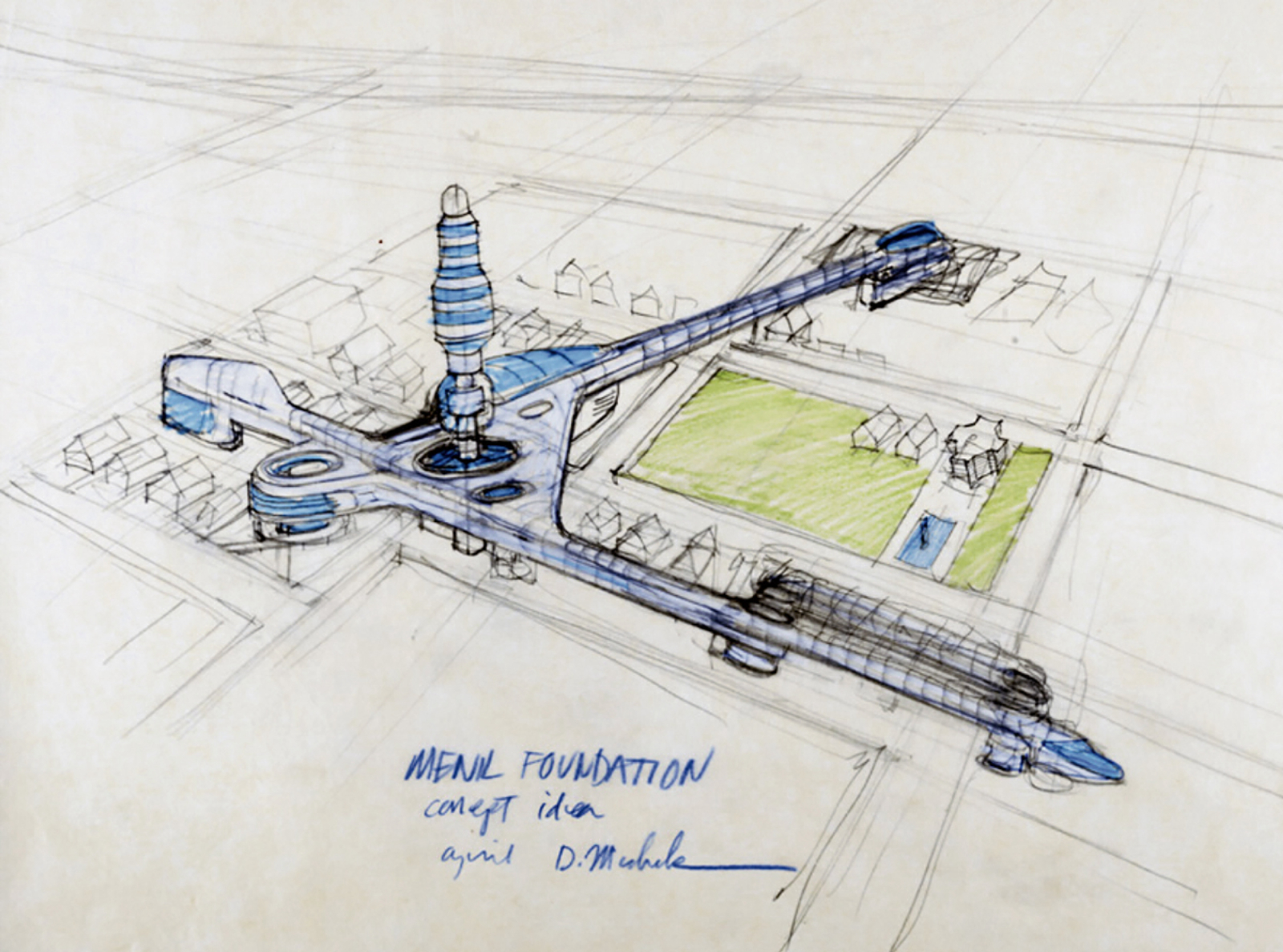

Barnstone’s office produced multiple schemes for the proposed Menil art center, which would house art storage primarily, along with offices, a conference room, and a small public gallery. The program grew to include a library for 3,700 volumes of “spiritual and philosophical” books, a workshop, and a small theater. Of the plans that emerged from Barnstone’s office, the most outrageous was a museum–art storage building designed by Doug Michels that was probably never shown to Dominique de Menil. It zoomed across the Menil-owned blocks like some futuristic transportation system, emanating from a central hub with a striped “tower.” In Michels’s scheme, buildings for different purposes (museum, auditorium, offices) touched down between the bungalows, with the large storage facility at the hub. This drawing (one among many for this project) demonstrates that Barnstone did not discourage design exploration; instead, he treated his employees as if they were students in his University of Houston design studio, encouraging them to search for innovative solutions, even if they were unlikely to be built.

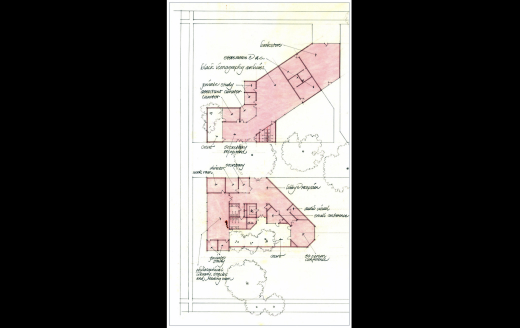

A more modest Barnstone proposal among those prepared between 1975 and 1979 called for two buildings, probably connected by a tunnel, as in other schemes. Different sites were considered for different proposals. This project was designed for the site where the Menil Collection museum eventually would be built, bound by Sul Ross, Mulberry, Branard, and Mandell. As in Renzo Piano’s Menil Collection museum, art storage would have occupied the second story in both buildings. Unlike Piano’s plan, Barnstone’s included a bookstore, conference rooms, study areas, and libraries, but essentially no exhibition space. One similarity, though, was the courtyards. When Dominique de Menil finally awarded the commission to Renzo Piano in 1981, it was a significant disappointment for Barnstone, who had spent four years working on plans while Mrs. de Menil sorted out her intentions.(1)