Modern in the Middle: Chicago Houses 1929–75, co-authored by Susan S. Benjamin and Michelangelo Sabatino, is the first survey of the classic twentieth-century houses that defined American Midwestern modernism.

The authors survey dozens of influential houses by architects whose contributions are ripe for reappraisal, such as Paul Schweikher and Winston Elting, Harry Weese, Keck & Keck, and William Pereira. As part of the Docomomo US Chicago Symposium, we planned to incorporate a number of these homes into special tours. However, due to the Symposium's postponement, we are now bringing the homes to you! Offered for the first time here is a excerpt of four selected homes that we hope will expand your understanding of modern in the middle.

Modern in the Middle: Chicago Houses 1929-1975, published by The Monacelli Press, is expected in August 2020.

Modern in the Middle: Chicago Houses 1929-1975

Author

Susan S. Benjamin and Michelangelo Sabatino

Tags

Modern in the Middle Part One:

Irma Kuppenheimer and Bertram J. Cahn House

Like millions of others, Irma (Mrs. Bertram J.) Cahn attended the 1933–34 Century of Progress International Exposition, where she visited the House of Tomorrow designed by George Fred Keck. But unlike anyone else, she came home desiring a summer house even more progressive than it, which she described as the “house of the day after tomorrow."(1) She envisioned a home that would be comfortable, low maintenance, and suitable for informal living - a servantless house that could be closed or opened easily with nothing that would deteriorate when it was unoccupied.(2)

Mrs. Cahn had been taking a class at the University of Chicago from preeminent historian Louis Gottschalk and happened to tell him what she was looking for in a house. Gottschalk was a neighbor of architects George Fred and William Keck in a three-unit cooperative apartment in Chicago’s Hyde Park/Kenwood neighborhood, and the professor arranged a dinner party where the Cahns could meet Fred. Her vision launched Keck on the design of an extraordinary passive solar house.

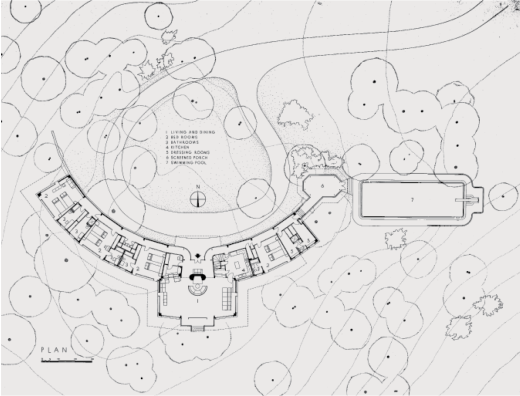

At the time Irma and Bertram Cahn planned their house, he was president of B. Kuppenheimer & Co., a men’s clothing business dating from before the Chicago Fire of 1871. The house was to be built on a forested thirty-one-acre property belonging to her father, Jonas Kuppenheimer. A large house existed on the property where her family spent summers and whose grounds were designed by Jens Jensen. The original house was demolished to make way for Mrs. Cahn’s dream, but her new home was carefully sited high on a bluff to retain views of the adjacent meadow, a signature Jensen design feature.

Irma Cahn had some specific design needs resulting from a horseback-riding accident when she was young girl that left her with a limp. There could be no stairs, floor rugs, or lamp cords to trip over. Because she was a heavy smoker, her spouse wanted the house to be fireproof. Furniture contained built-in ashtrays, and tables had aluminum surfaces. To meet the Cahn’s requirements, Keck designed a one-story, steel-frame house sheathed in stucco. Completed in 1937 at a cost of $125,000, it had four bedrooms, six baths, and a screened porch overlooking a swimming pool.

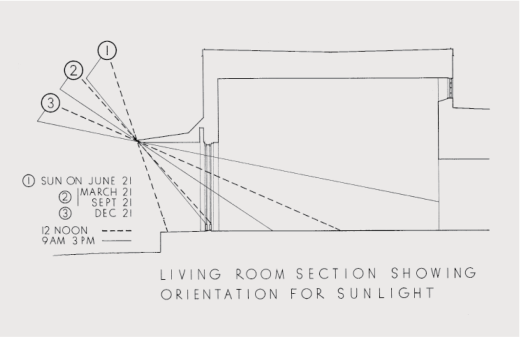

The house was crescent shaped with the north-facing concave curve embracing a circular drive to create an entrance court. To ensure privacy from the drive, Keck designed a hallway running the length of the interior curve to serve as a buffer between the other spaces. Glass block windows along the hallway’s exterior wall allowed for the exchange of light while maintaining privacy. The living room and bedrooms were positioned in the rear of the house, which followed the convex curve; all the walls had large clear glass glazed walls facing south. Electric windows that could recede into the basement—like those found in Mies van der Rohe’s Tugendhat house in Brno - were planned but deemed too expensive and eliminated from Keck’s design.(3) The Cahn House did incorporate features on the cutting edge of Keck’s experimentation in passive solar design. Broad eaves and external, chain-driven Venetian blinds shaded the glass openings, protecting the interior of the house from overheating in the summer, while allowing the sun to penetrate and warm the interior in the winter. The living room projected out from the southern curve of the house, with three glazed walls providing both morning and afternoon light as well as dramatic views of the meadow.

The interior was kept sparse, with built-in cabinetry and furniture. The living room was the home’s most dramatic space, with a high ceiling painted cobalt blue, walls and furniture in yellow, and black rubber flooring. Instead of a separate formal dining room, square tables could be reconfigured for bridge games or to accommodate dinner guests in the open space. Dining chairs would also function as movable seating elsewhere in the room. The major fixed piece of furniture was a semi-circular sofa, with cobalt blue striped upholstery, facing the fireplace.

Mrs. Cahn wanted to be able to read from anywhere. To accomplish this without any lamps, eighteen recessed pinhole ceiling lights were installed that could illuminate any area of the room. Because of the hard surfaces in the combined living and dining room, its acoustics were excellent for listening to live string quartets or recorded music. Loudspeakers on casters could be tuned by remote control. Irma Cahn commented, "We like the house because it is spacious, colorful, bright, restful, and in harmony with the surrounding landscape."(4) It also met the Cahn’s request for a turnkey, low-maintenance home that looked modern and accommodated a casual lifestyle for a family that could easily afford more lavish living. Their taste for modern architecture was atypical for wealthy Lake Forest residents who generally preferred houses based on traditional historic styles.

The Cahn House was included along with numerous other International Style homes in The Modern House in America, published in 1940.(5) Although the house remains standing, it has suffered substantial alterations.

Notes

- William Keck, Oral History of William Keck / Interviewed by Betty J. Blum, Compiled under the Auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project, the Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings, Department of Architecture, the Art Institute of Chicago, rev. ed. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2001), 100.

- “George Fred Keck Architect: House for B. J. Cahn, Lake Forest, Illinois,” Architectural Forum 71, no. 1 (July 1939): 13, as quoted in Robert Piper Boyce, Keck & Keck (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993).

- The mechanical windows were priced at $40,000. Keck, Oral History, 109.

- “George Fred Keck,” 13.

- James Ford and Katherine Morrow Ford, “George Fred Keck, Architect: House for B. J. Cahn, Lake Forest, 1937,” in The Modern House in America (New York: Architectural Book Publishing, 1940). Republished as James Ford and Katherine Morrow Ford, Classic Modern Homes of the Thirties: 64 Designs by Neutra, Gropius, Breuer, Stone and Others (Mineola, NY: Dover, 1989), 66. In their preface, James Ford and Katherine Morrow Ford extend their appreciation and guidance in the selections of much of the material in the book to Professor Walter Gropius, chairman of the Department of Architecture of the Graduate School of Design of Harvard University, and to Dr. Sigfried Giedion, general secretary of the International Congress of Modern Architecture, 7.

About the Author

Susan S. Benjamin is a noted historic preservationist and published architectural historian based in Chicago. Her office, Benjamin Historic Certifications, has initiated the landmarking of notable historic buildings of all periods, in Chicago as well as throughout Illinois. Benjamin lectures frequently on a wide variety of topics, from historic landscapes to Chicago's residential architecture of the nineteenth century to the present. She is coauthor, with architect Stuart Cohen, of two important books on historic residential architecture in Chicago: North Shore Chicago, Houses of the Lakefront Suburbs: 1890-1940 (2004) and Great Houses of Chicago: 1871-1921 (2008).