The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book Modern in the Middle: Chicago Houses 1929-1975, by Susan S. Benjamin and Michelangelo Sabatino, published by The Monacelli Press. Expected in August 2020.

Use code MODERN20 to receive 20% off pre-orders of the book through the Monacelli website.

Modern in the Middle Part Four:

Doris Curry and Jacques Brownson House

Jacques Calmon Brownson has received praise for his civic buildings, especially as chief architect of the award-winning Chicago Civic Center (1965, renamed Richard J. Daley Center in 1979) during his time with C. F. Murphy Associates.(1) In the 1990s, Paul Gapp, architecture critic at the Chicago Tribune, listed it among the city’s ten most important postwar works of architecture.(2)

Jacques Brownson started his undergraduate professional degree at IIT in 1941, shortly after the arrival of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe as the new director in 1938. Brownson acquired experience in the design-build process very early when his father agreed to build and sell a house with Brownson as apprentice builder in order to pay for his architectural education with profits from the sale.(3) Although the war intervened, upon his return to Chicago after serving with the US Army Corps of Engineers (from 1943–46), Brownson re-enrolled at IIT and in 1947 was awarded the opportunity to participate in the Build-It-Yourself House initiative sponsored by Popular Mechanics magazine.(4) Published in both the April and May issues of the magazine, the “modified Cape Cod” house that twenty-three-year-old Jacques, with the assistance of his spouse Doris, designed and built in his hometown of Aurora opened to the public in Spring 1947.(5) In the demonstration photographs published in the April 1947 issue, Jacques and Doris often appear working side-by-side to realize the house.(6) The sale of the Popular Mechanics Build-It-Yourself House in Aurora allowed the Brownsons to purchase property for their future modern house in nearby Geneva.

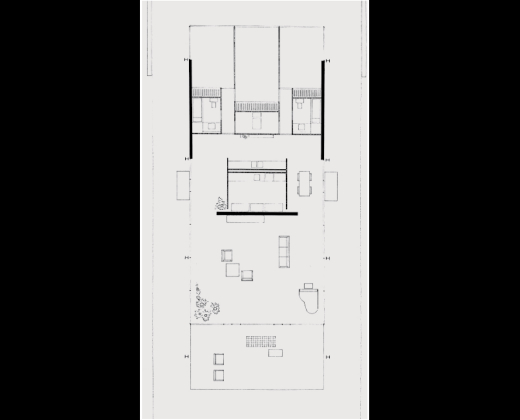

During the postwar years there was a growing trend among architects to live in Chicago-area villages and cities and either commute to work or establish home offices. Brownson designed and built a steel-and-glass one-story pavilion on a wooded site along the Fox River for Doris and their children.(7) The Brownson House lies flat on the ground—as does Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan completed earlier in 1949, and unlike the elevated Edith Farnsworth House (p. 162) that was also under construction in nearby Plano. The pavilion effect was reinforced by the wooded setting in which hawthorn trees were planted with the guidance of landscape architect Alfred Caldwell, Brownson’s former teacher at IIT. Brownson wrote: “In a glass pavilion, the spectacle of nature is always before you.”(8) The steel-framed roof plate is suspended from four rigid steel girders held up by black steel columns. In describing the spatial and material strategy of separating and demarcating living areas (defined by floor-to-ceiling glass walls) from sleeping areas (brick infill with windows) at the rear of the house. Brownson indicated that the “Geneva house is really two houses in one. If you look at the plan, it is separated very clearly by a wall that says that one part is very private, and the other part is the public space, which is the front part. It’s a house in which the difference shows.”(9)