The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book Modern in the Middle: Chicago Houses 1929-1975, by Susan S. Benjamin and Michelangelo Sabatino, published by The Monacelli Press. Expected in August 2020.

Use code MODERN20 to receive 20% off pre-orders of the book through the Monacelli website.

Modern in the Middle Part Three:

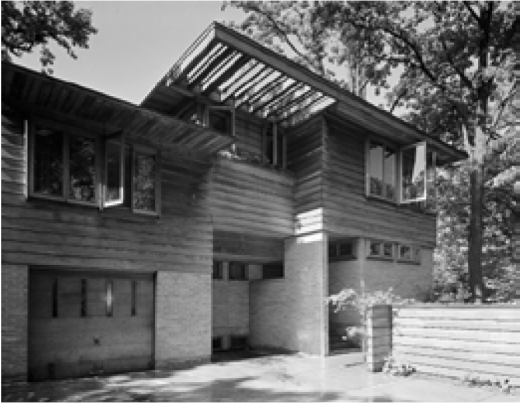

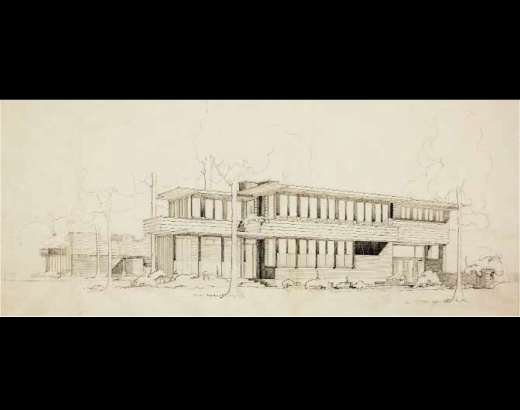

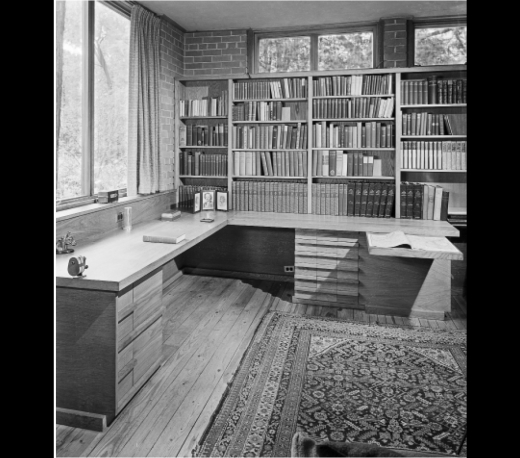

Ellen Newby and Lambert Ennis House

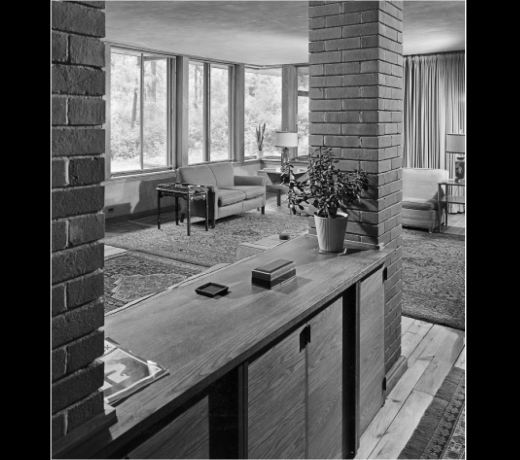

The house William Deknatel designed for prominent Northwestern University English literature professor Lambert H. Ennis and his spouse, Ellen Newby Ennis, reflects Deknatel’s training at the Taliesin Fellowship. Deknatel—along with his spouse, Geraldine, John H. Howe, and Wesley Peters—was among the charter applicants for membership at Wright’s school when it was established in 1932. While in temporary quarters, he and his colleagues worked directly under Wright on construction of the Fellowship buildings.(1) This gave Deknatel hands-on experience with Wright before setting out to establish his own practice.

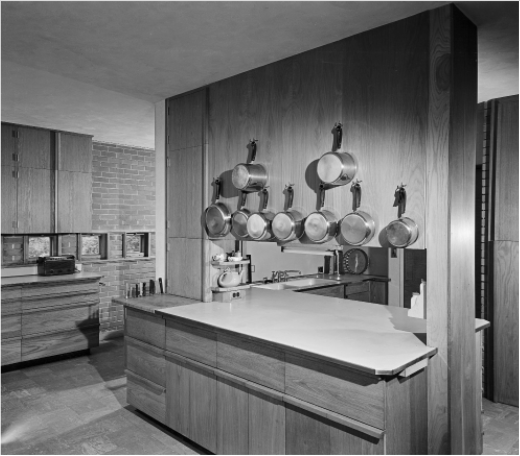

Deknatel was born in Chicago in 1907 at Hull House, a settlement house where his father was Jane Addams’s volunteer secretary-treasurer and his mother a kindergarten teacher. He graduated from Princeton University in 1929, leaving the following year for Paris to attend the École des Beaux-Arts. It was here that he met his spouse Geraldine Eager, an interior design student. The couple returned stateside in 1932, and after spending two years at the Taliesin Fellowship, they returned to Paris in 1934 for two years in André Lurçat’s office. In 1937, Deknatel settled in Chicago and opened his practice. During the 1940s and ’50s he designed a number of suburban houses that incorporated both Wrightian and International Style elements. Geraldine often served as interior designer. William Deknatel’s most prominent commission was for Celeste McVoy and Walter J. Kohler Jr., a member of the Kohler family whose company produced bathroom and kitchen fixtures and who served as Governor of Wisconsin from 1951–57. The modern estate house “Windway” in Kohler, Wisconsin was built in 1937–38 and reflects the collaboration with Geraldine for its interiors.(2) In 1939–1940, Deknatel designed Good Housekeeping’s “Better Living” House.(3)