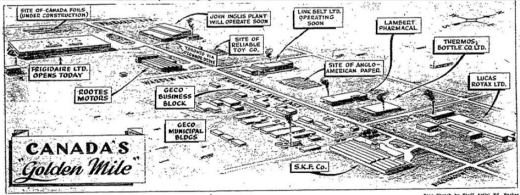

The Golden Mile can be found fifteen kilometers to the northeast of downtown Toronto, Canada and was one of the nation’s first industrial complexes that transition to commercial in the post-war area. The Golden Mile was once a place where iconic corporate campuses and companies like IBM and others served as catalysts for economic development while supporting the growth and expansion eastwards alongside iconic planned residential subdivisions, which sprang up to house the new industrial workforce and support their modern lives. “Large businesses including General Motors, Volkswagen, Frigidaire, Thermos, and Svenska Kullagerfabriken (SKF) rapidly moved into the area and started manufacturing cars, toys, appliances, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and candies. Soon, the area gained a reputation, and younger companies relocated to the Golden Mile to signal their modern development and prosperity.” (Heritage Toronto 2024)

American Influence and the Canadian Corporate Campus: Re-Imagining the Golden Mile

Author

Eric Nay

Affiliation

OCAD University

Tags

During the 1950s and 1960s much of Toronto’s industry relocated to the burgeoning suburbs of the Don Valley, drawn by lower taxes, new highway systems, improved transportation networks and the lure of more bucolic and less congested surroundings. Industry facilitated the eastward expansion of the city and a new imaginary of what a modern Toronto would look like. The Golden Mile, situated within the grand development scheme of the Don Valley, epitomized this spirit of growth and optimism framed by a post-war boom focused on integrating industry and domesticity couched within the fantasy of the ideal suburban lifestyle as the driver of modern urban form. This ethos is described in detail in The Interface: IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design, 1945–1976 (Harwood 2011), which helped supplied an integral chapter in the story of how corporate architecture and design shaped the postwar imaginary.

In another related text, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Harris 2013), Dianne Harris presents an analysis of suburban tract housing in the 1950’s in Los Angeles as a method to focus on the racializing intentionality of the suburban tract home to assimilate “Others” into a culture of “whiteness” through design using her parents as a central case study. Harris’ analysis provides design-based evidence for how architecture was used strategically to produce both a desire for a homogenous modern lifestyle and to assimilate “Others” into an idealized fantasy of white suburban life through design. Imagine the carefully planned and spatially orchestrated urban landscapes embodied in the suburban tract home and how behaviours were structured and controlled using devices like large picture windows to make interior lives publicly visible or the systemic ritualization of activities like lawn mowing and car washing as methods of coercive assimilation. These are just a few of Harris’ provocative hypotheses.

Unpacking such theories, whether they are sociological or behavioural, while looking closely at the fading shells of corporate campuses in Toronto, produces similar opportunities to re-think postwar fantasies, particularly regarding identity, race and space. The corporate campus projected and maintained idealized lifestyles, fantasies and imaginaries that need to be revisited to help us understand both current trends in contemporary thought and architectural criticism, and the ongoing growth of Toronto eastward along the path established by the Golden Mile. The corporate campus is worthy of a deeper look and may be even more important in its current varied states of decay, adaptive re-use or demolition. In this article I will look at examples of all three.

Drawing from popular magazines, aspirational site plans and lurking within architectural floor plans, the corporate campus can be seen as an ideological form of Gesamtkunstwerk, roughly translatable as a total work of art, that set the tone for modern life in the Don Valley, not unlike Levittown and other American models. This tone was clearly being emulated to project a fantasy of an idealized (American) vision of suburban life in the 1950’s, which idealized white, middle-class identities, but which would be reshaped within the context of postwar boom Toronto in the 1960’s and 1970’s as immigration policies and urban growth patterns would re-write a new (less white) counter-narrative.

The corporate campus and the master planned expansion of the Don Valley depended upon the imagery of the corporate campus and its ancillary architectural types to shape the initial eastward expansion of the city. This legacy and the patterns the corporate campuses established in the Golden Mile are of great historical and cultural significance, as are their demolition, adaptive reuse and transformation. The corporate campus proved to be a critically important ideological tool in helping wave after wave of newcomer find affordable homes, jobs, safe neighborhoods, good schools and other opportunities, while laying the groundwork for Toronto’s expansion east.

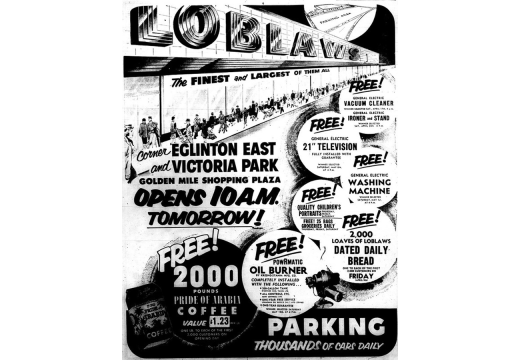

The seeds for imagining and branding the corporate campus can be seen in the initial advertising campaigns and sales pitches staged by developers and municipalities, like the City of Toronto. These campaigns were hoping to capitalize on the Americanization of the postwar suburban fantasy and its Canadian apparition, while simultaneously encouraging the industrial growth needed to achieve the economic prosperity desired. This growth remains a defining characteristic of this part of the city, as opposed to others that are free of all signs of industrialization.

Today, about half of Toronto’s residents were born outside of Canada and over 200 ethnic origins are represented among its inhabitants. As a result, Toronto prides itself on being a city of neighbourhoods as befitting the Canadian Charter of Rights and national desires to not “assimilate” newcomers into a “melting pot,” but rather to employ a “mosaic model,” where one’s cultural identity can be retained as a goal. This ethos shapes the story of the Golden Mile and the Canadian corporate campus as well. The influence of corporations and the centrality of the corporate campus on the contemporary psychogeography of Toronto on the Golden Mile, as a particular urban node, remains an indelible spatial narrative that provides a significant example for how the American corporate campus moved north as an idealized fantasy, but became

distinctly part of the Canadian national narrative over time.

“Along the strip, backhoes sleep between dirt piles in huge vacant lots and, where old factories do survive, it's only because new faces have been grafted onto them, such as the former Rootes Motors building at Warden and Eglinton, where a Vietnamese restaurant, Sally Ann, flea market, jewellery exchange and a courthouse now rub shoulders.” (LeBlanc 2006)

The Golden Mile is historically and culturally significant in its capture of an era shaped by a desire to emulate the American Dream through the postwar suburb and visons of prosperity that have been continuously shaped and reshaped by waves of newcomers and further expansion eastward extending the trajectory of the Golden Mile. During the Second World War, the area of Scarborough now known as the Golden Mile and the Don Valley was originally dubbed “the Golden Mile of Industry," indicative of its originators’ intentions. In the decades after its inception in the 1950’s, the Golden Mile was quickly transformed into one of Canada's first model industrial parks and commercial centers. This vision would help shape the entire Don Valley by creating a new epicenter for modern housing for thousands of workers who would work alongside their neighbors in the factories and offices that would stimulate the expansion and variety of consumer goods needed to fill these new houses and fuel the desires of an ever-expanding city.

Numerous examples of corporate campuses situated along Eglington Avenue or adjacent to the Golden Mile have already been demolished, including Toronto’s massive Celestica campus. The historically significant Celestica campus sat at the corner of Eglinton Avenue East and Don Mills Road, which at its peak was made up of nearly 1.3 million square feet of office, manufacturing, and warehouse space comprised of multiple buildings. Significantly, the site was previously home to IBM’s Canadian manufacturing plant, which later became Celestica, a multi-national electronics manufacturing services company and offshoot of IBM. The site has since been demolished and is now being redeveloped as one of the largest infill mixed use housing and retail development projects the city if Toronto has ever undertaken.

An example of a corporate campus in the same area that remains in use, but is rumoured to be pending demolition, is the Scarborough corporate campus of Scotiabank. Scotiabank’s Scarborough corporate campus is located in the heart of the Golden Mile right on Eglinton Avenue, and remains as one of the few corporate campuses that have not been transformed into small scale retail shops or manufacturing facilities, private for-profit colleges, etc. Rumours are circulating that the property has already been sold with a leaseback arrangement or that the property has already been sold to developers just waiting to convert the massive tract of land into condominium towers, once the remaining few workers that still occupy the space have been relocated or eliminated.

A more engaging and interesting alternative for re-imagining and preserving the legacy of these corporate campuses can be seen nearby in Thorncliffe Park, a neighbourhood adjacent to the Golden Mile. A new Costco, the ultimate global corporate tenant, has been designed to thoughtfully re-inhabit and preserve the shell of an iconic and well-known Coca-Cola corporate campus that was at risk of demolition. The Coca-Cola site, which had been registered as a heritage site by the City of Toronto, consisted of multiple buildings including a factory, bottling facilities and offices. The Coca-Cola campus was preserved in part to embrace adaptive re-use and to appease critics arguing against the destruction of the defunct heritage site. Meanwhile desires to invite the retail giant into the neighbourhood by the community and developers were also appeased. The Costco re-development of the Coca-Cola campus preserved key portions of the existing Coca-Cola campus while adapting the massive spatial needs of the retail giant (warehouse space and parking) into the design as a form of compromise, which works surprisingly well.

The Canadian corporate campus’s legacy in Toronto, as seen on and adjacent to the Golden Mile, remains as indisputably significant marker for showcasing the influence of American urban form on Canadian life after the war and its ongoing legacy today. The issue of whether these dated corporate behemoths are worth preserving, destroying or adapting is a problem best explored on a case-by-case basis. However, the opportunity to look at an entire urban zone that captures a specific time and space in the city’s growth and expansion, as well as its resulting cultural transformation in the years following, also tells a story shaped by American influence, and then reshaped by a distinctly Canadian narrative and context. This itself needs recording as a form of urban history.

What will become of these corporate campuses and their legacies remains unknowable, but I suspect most, if not all, will be destroyed to make way for new condominiums and much needed housing. The city is also currently in the final stages of completing a new light rail line that runs directly down the center of the Golden Mile, furthering the eastward expansion of the city that the Golden Mile began more than a half a century ago. The Canadian version of the modern American corporate campus is worth further exploration and analysis, particularly before more of these campuses, like the Celestica complex, are erased from public memory. I also personally shop at the Costco mentioned and my favorite part of that experience is watching people read the information posters that describe the history of the Coca-Cola campus conveniently placed to read as you await your $1.50 hot dog. The historic preservation of modern architecture will need to take on many different forms and attitudes to be successful and effective in the future.

About the Author

Eric Nay is a professor of architectural history & theory + environmental design at OCAD University in Toronto (Canada) and a lecturer in human geography in the Department of Geography and Environment at Mt. Allison University (New Brunswick, Canada). Trained as an architect, Eric’s professional experience includes practice in New York City, Chicago and California. Eric has taught across a range of design disciplines at the University of Toronto (Canada), the University of North Carolina (US), the American University of Sharjah (UAE), the University of California at Davis (US), the Irish Architecture Foundation (Ireland) and others. His work has appeared in publications including ICOMOS (Germany), Ediciones ARQ (Chile), Spool (Netherlands), Alternatives Journal (Canada), Open House International (UK), et. al.