From an adapted barn in Locust Valley, Richard Lippold spun wire into gossamer threads to create other worldly compositions. He eschewed organized religion but was deeply connected to the natural world and communed with the metals that composed his sculptures. His work has been described as a “para-architectural practice,” and early site-specific commissions for The Four Seasons Restaurant at the Seagram Building, the MetLife Building (formerly Pan Am), and Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center established him as a trusted collaborator with modernist architects like Philip Johnson, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe. His work – intricate wire sculptures characterized by their effect of shimmering like rays of light – was well suited for the revered interiors of sacred spaces.

The Ascetic Artist

Author

Marie Penny

Affiliation

Planting Fields Foundation

Tags

Lippold spent his formative years in the Midwest before arriving in New York City in 1944. He obtained a degree in Industrial Design (per his father’s urging for a more lucrative career as an artist) from the Art Institute of Chicago and a BFA from the University of Chicago. Although he did not set out to become a teacher, he found work teaching at Black Mountain College (alongside Buckminster Fuller), as well as Hunter College, and Goddard College to name a few schools, where he taught students to expand their minds beyond formulaic thinking. He arrived in New York when post-war artists had ready access to industrial materials and modern architects were given carte blanche to incorporate modern craftsmanship, decoration, and art into their buildings.

Modernism and Movement

To finance the move to New York from Detroit, Lippold and his wife Louise, a choreographer and dancer, sold a Hammond organ they had received as a wedding present. Almost ten years later, in 1955, Lippold installed a custom-made wood pipe organ from Denmark in his Locust Valley home – he added his own personal touch to the front of the organ with his signature network of fine gold wire. This enormous instrument, where Lippold sat and played Bach, speaks to his devotion, a type of divinity that he was able to create independent of any structured rituals.

The grand estates of Long Island’s Gold Coast were going through their own transformation during the midcentury. Some became college campuses, historic house museums, or in the case of the Meudon estate, partially adapted by modern architect Herman Herrey. Lippold was acquainted with the Meudon estate prior to living there, as he attended the Locust Valley music festival (hosted there by Alma Morgenthau) and mused, “this is how the other half lives.” After Morgenthau passed away, he acquired the stable-turned-music-shed through his dealer Marian Willard – who inherited the site – and made it into his studio. This space, shaped by modernism and music, became his sanctuary and where he designed Trinity.

Trinity 1960

Architect Pietro Belluschi, known for his modern American vernacular churches in Oregon, and affinity for wood and abundant natural light, relocated to the east coast to serve as dean of the School of Architecture and Planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He was commissioned to design a chapel, among other buildings, at Portsmouth Abbey, home to a Catholic Benedictine boarding school.

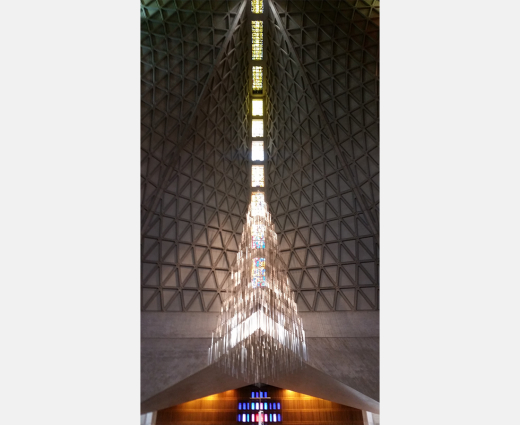

The octagonal chapel draws inspiration from a sixth-century Italian church built during Pope Gregory the Great's (the patron saint of Portsmouth) lifetime. The chapel has been likened to an “American polygonal barn” with its use of exposed timber. In this case, the architect and artist did not work together directly; Bill Burden, a former Museum of Modern Art chairman, commissioned Lippold for the project in 1957.

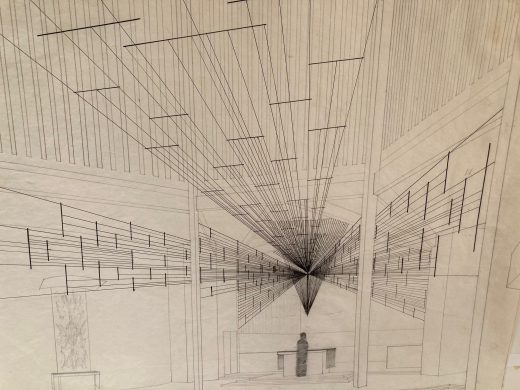

The Benedictine monks approved Lippold’s conceptual sketch but did so with a leap of faith. The order of Saint Benedict may be the oldest of all religious orders in the Latin church, however, they embraced modernism during the midcentury. Along with Portsmouth Abbey, two other modern Benedictine churches were designed in the early 1960s: Marcel Breuer’s St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota and Phillip Johnson’s addition to St. Anselm’s Abbey in Washington D.C.

Lippold responded to the tripartite nature of the church by connecting the altar, nave, and retrochoir under his signature luminous gold wires. In his own words he described the trinity of forms symbolizing “the Father (monks), the Son (student boys) and the Holy Ghost (the descending cloud enclosing the Corpus).” Trinity responds to the work of other artists in the space: it’s in dialogue with Gyorgy Kepes’ colorful stained-glass windows through the reflection cast from the aluminum bars suspended from the wires, and it seamlessly surrounds and radiates from the bronze and steel crucifix designed by Swiss artist Meinrad Burch.

Its airiness and see-through quality somehow fill the interior space yet does not compete or overpower the architecture. Residing now full-time at the Abbey allows me the privilege of appreciating this art every single day.Brother Sixtus Roslevich, Order of Saint Benedict (OSB), May 2025

Lippold reported that Trinity was his first physically challenging project: he had to do much of the work independently as his assistant, the artist Ray Johnson, fell ill. Lippold’s fingers became infected by raw cable ends and had to be bandaged, making the threading work all the more painful, and he swayed with motion sickness on top of the fifty-foot rig. Although Belluschi was not involved in the commission, according to Lippold when he saw the completed work, he was moved by “the glory of the sculpture, lifting the building spiritually.” Ten years later, in 1970, Belluschi commissioned Lippold for a site-specific installation, Baldacchino, at the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Assumption in San Francisco.

Lippold went on to design several other unrealized installations for sacred places including the Crystal Cathedral and Our Lady of the Angels in California, and a new Baldacchino for the historic Viterbo Cathedral in Italy. In 1970 he was made an honorary member of the Guild for Religious Architecture and in 1982 architect Minoru Yamasaki commissioned Sun Wing and Sun Tree for Shinji Shumeikai Shrine near Kyoto, Japan.

Ego and Edifice

The relationship between architect and artist is often tumultuous, however, Lippold was frequently lavished with praise from architects who welcomed his sensitive approach to the site. Philip Johnson acknowledged that, “he is very clear about the architectural requirements of a space; in other words, he does not set out to build a monument to Richard Lippold.” Walter Gropius proclaimed, “All my life I have tried to cooperate with painters and sculptors to create works to be at one with my buildings; Lippold is the only one whose work comes to one with our buildings. The only one!” Architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable famously scoffed at the notion of integration between architect and artist and argued that art should be a counterpoint to the building. And yet Lippold acquiesced that “my constructions are a reflection of the space; they are not designed as personal statements of discord or irony.”

The inner sanctum of a sacred place is where one comes to connect with community and the divine, but also to dive deeper into the self. Lippold understood the path toward the granular, the dissolving of the self into space. His sculptures, while in a state of stasis, appear alive with movement, each delicate piece is part of a greater whole:a school of fish swimming in unison. He once remarked that, “you can learn a great deal from walking”, and his work is an expression of those ribbons of thought, the manifestation of perambulations. Those seeking figurative representations within a sacred place may be slow to warm to rays of light made of wire, and yet despite one’s preference, they are instantly recognizable as spiritual, as divine.

As in a love affair, when sacrifice of one’s self to love itself opens new worlds of understanding of the human condition, so, I believe, the ascetic artist, by bending his forms to the master proportion and social creed expressed in a good building, can fulfill humanity.Richard Lippold, The New Yorker, 1963

About the Author

Marie Penny is the Michael D. Coe Archivist for Planting Fields Foundation – a historic site in Oyster Bay, New York. She previously held positions as the archivist at the architectural firms of Rafael Viñoly Architects and Meier Partners. Penny presented on the Tropical Ranch at the Docomomo US National Symposium in Miami (2024). She has been published in ARRIS – the Journal of the Southeast Chapter of Architectural Historians – and The Magazine Antiques.