Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio in Wisconsin, is an eight-hundred acre estate situated in a rural, rolling landscape. It comprises a sprawling residence and office building, as well as a school, houses, a dam, ponds, a windmill, and farm buildings. Taliesin is significant due to its architectural character. It features representative works spanning Wright’s entire career from the 1880s through the architect’s death in 1959. The site is also significant because of its association with Wright’s elaborate and well-documented model for teaching and living, the Taliesin Fellowship.

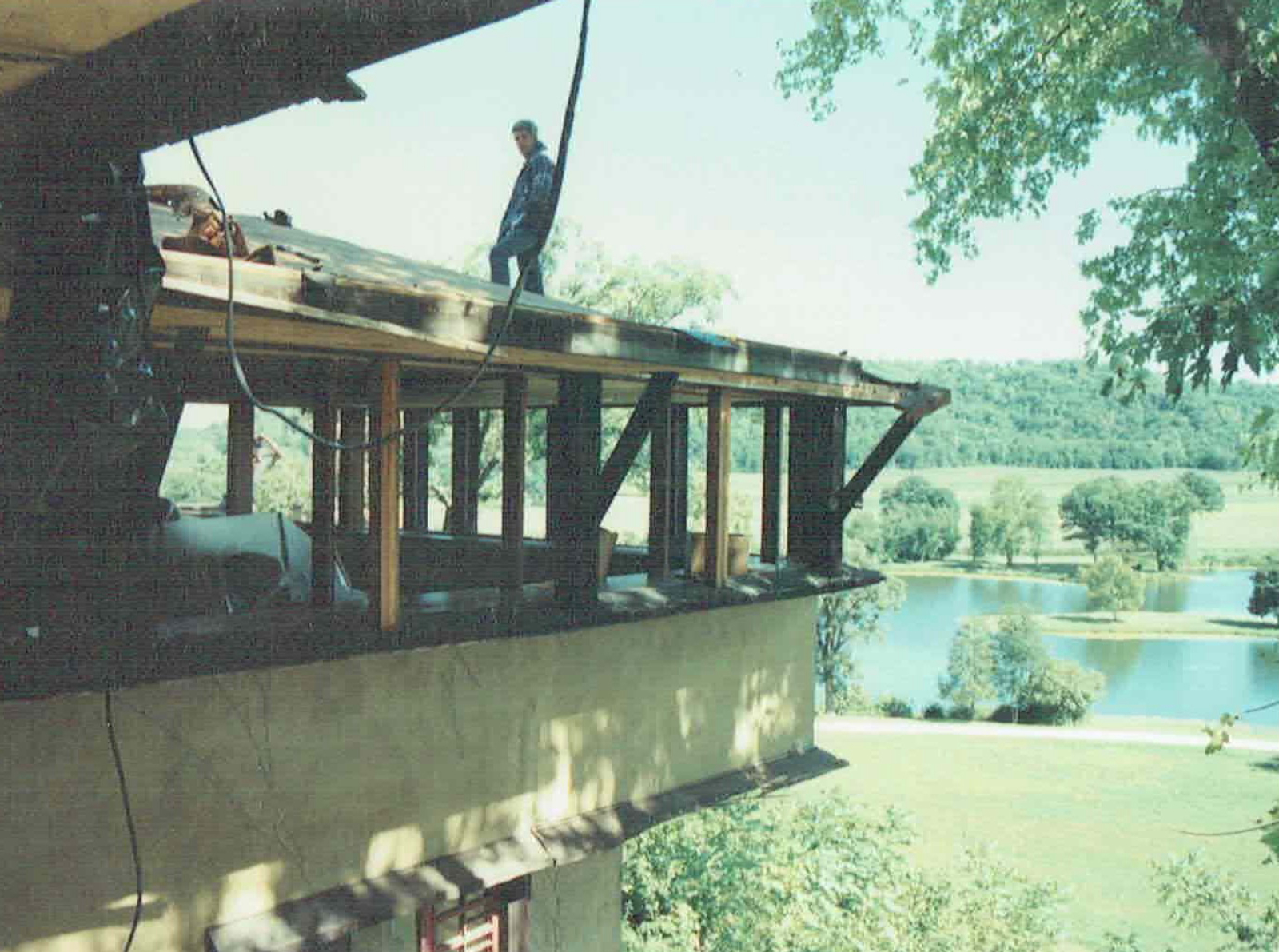

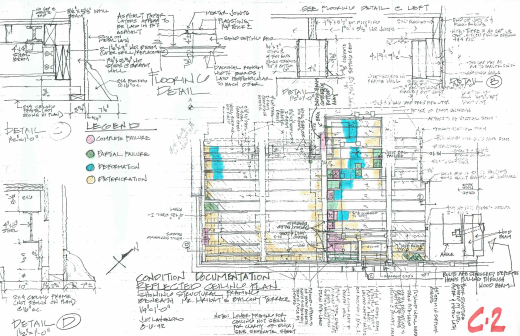

Today, Taliesin is open for public tours and also houses a resident community made of current students, faculty, interns, and even a few older members of the Fellowship, Wright’s own colleagues often referred to as the Legacy Fellows. The buildings on this site are materially difficult to maintain. Students and apprentices were responsible for much of Taliesin’s construction, and buildings were not built to contemporaneous codes, let alone modern standards. Additionally, Wisconsin’s harsh climate often accelerates the deterioration of wood details, plaster, stucco, and Taliesin’s cedar shingle roofs. Spaces within Taliesin have been selectively restored, rehabilitated, preserved, or modified over time. Caretakers, residents, and preservationists must grapple with Taliesin as both a historic object and living site.

As we approach Wright’s 150th birthday in June, we can also note that it has been fifty-eight years since the architect’s death in 1959. 2017 also marks the 26th year of Taliesin’s preservation-focused non-profit, Taliesin Preservation Incorporated (TPI), and discussions surrounding Taliesin’s management and preservation treatment stretch back multiple decades. By looking at ways in which the buildings have been treated through time, it is possible to unpack some of the methods, means, and values inherent in preservation work, especially values specific to Taliesin and Wright’s legacy. The site is a rich example that illustrates many ways in which a place can be preserved. This article will highlight just a few interventions manifest at this complex site.