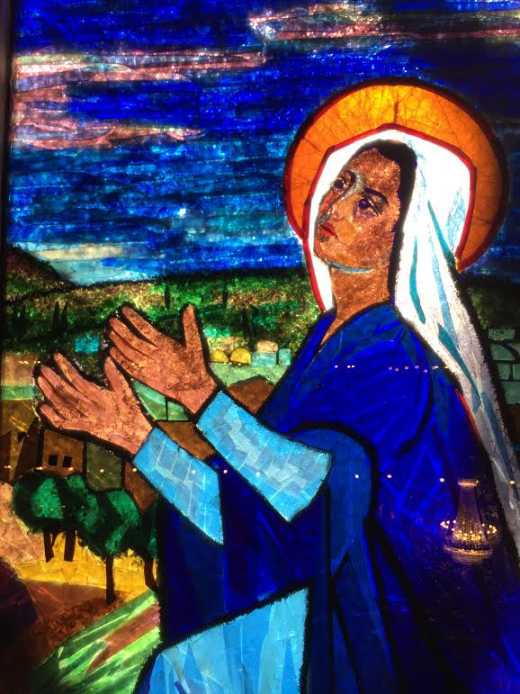

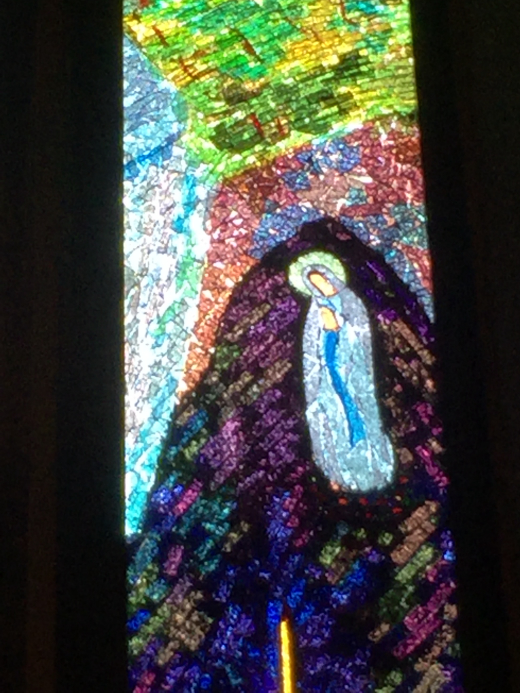

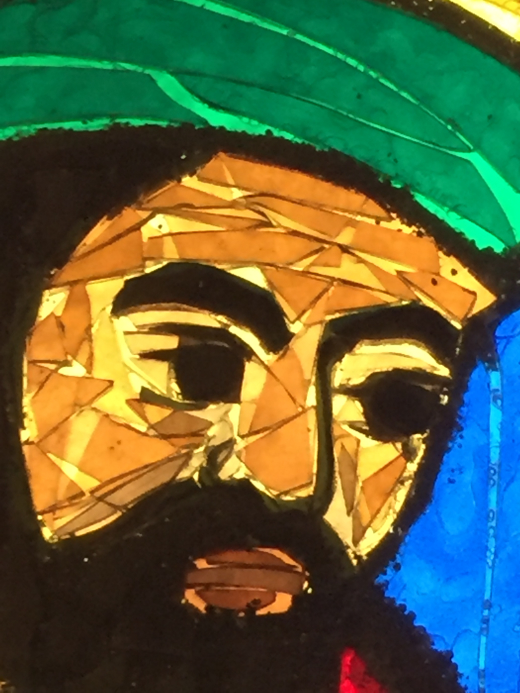

In 1953, the Chor-Bishop Mansour of a Brooklyn Heights church had heard whispers of a new French stained glass called gemmaux. Excited by the prospect of presiding over the first church to have all of its windows done in this style, Chor-Bishop Mansour Stephens of Our Lady of Lebanon promptly commissioned 10 windows from the artist that developed the technique, Jean Crotti.1

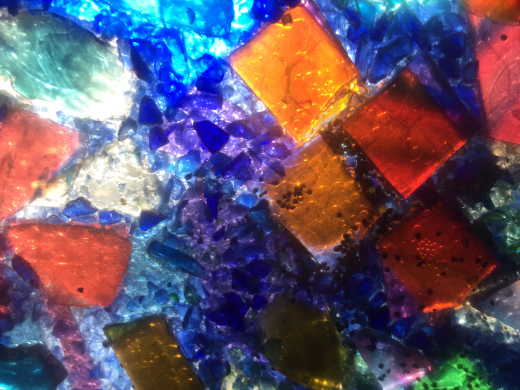

Years before the technique ever graced full-scale windows, it was first limited to small works. Swiss-born, France-trained Crotti would layer and adhere colored glass pieces onto a transparent panel and put them on view in front of a light box. The artist collaborated with Roger Malherbe-Navarre, a physicist and lighting expert, to help him perfect these adhesives and light boxes. Crotti sought a permanent adhesive that would fuse the glass together, but would also be completely transparent and not obstruct the light.2