In 2023, the Wisconsin State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), the Milwaukee Historic Preservation Commission, and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee launched a project to survey Milwaukee’s 20th-century houses of worship. The Wisconsin SHPO, like many others, uses a portion of its annual federally allocated Historic Preservation Fund (HPF) to sponsor community projects around the state. Community surveys, like the one in Milwaukee, offer opportunities for preservation planning; identifying threats and preservation priorities; and strengthening connections between property owners and local and state preservation offices.

The Milwaukee thematic survey accomplished all of the above objectives, eventually cataloguing nearly 200 churches, synagogues, and related buildings in the city. The survey also identified three dozen properties that met the criteria for historic designation, two of which are currently in the process of being listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

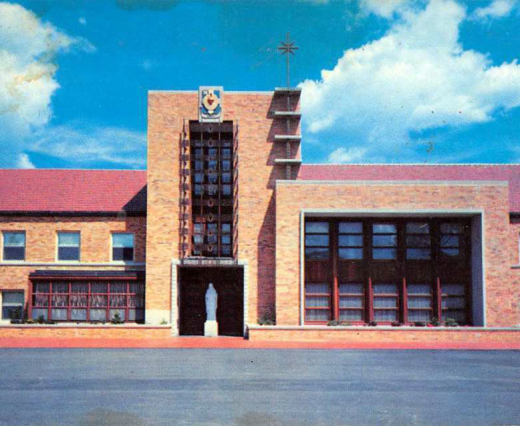

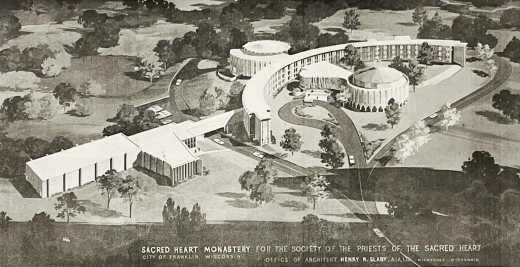

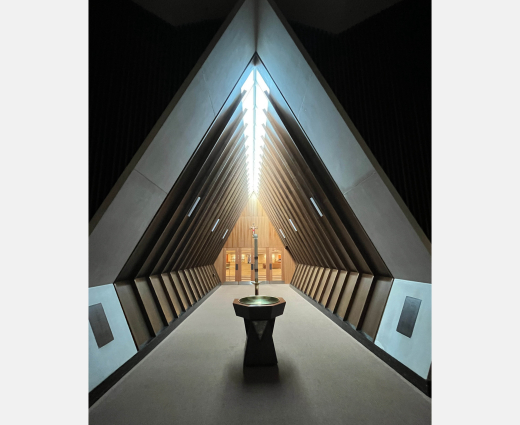

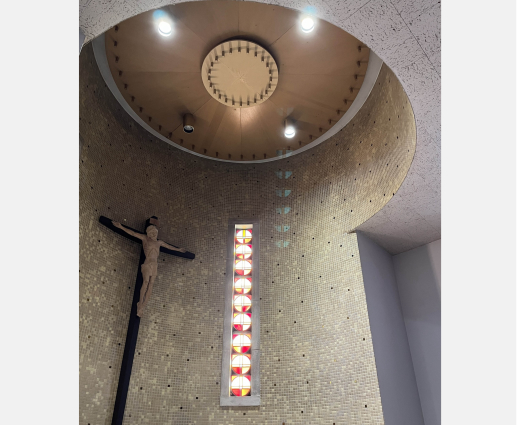

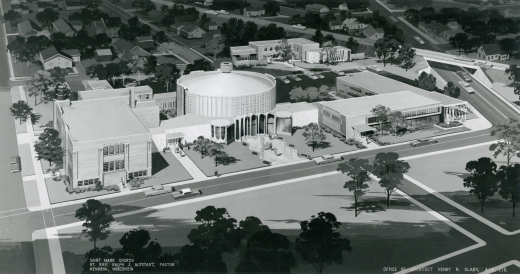

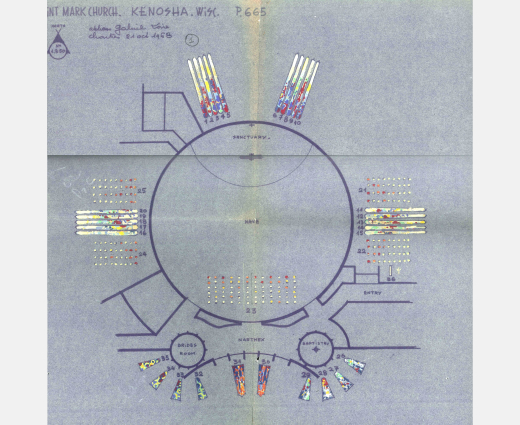

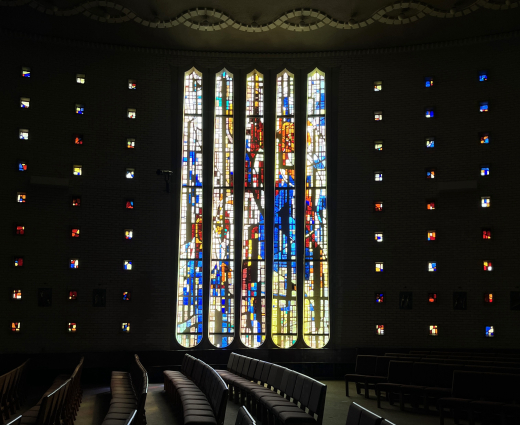

The survey had one unexpected outcome, however – the discovery of a relatively unknown architect whose work extended beyond the geographic boundaries of Milwaukee: Henry R. Slaby, AIA. Slaby (1906-1995) was born in Milwaukee and apprenticed in the local architectural office of Herbst & Kuenzli. This firm was a prolific designer of churches, and family lore tells that Slaby’s first project there was detailing the tower of St. Sebastian’s, an elaborate Late Gothic Revival church constructed in 1929 for an affluent neighborhood of Milwaukee. After striking out on his own (and completing a few Depression-era commercial projects to pay the bills), Slaby would specialize in Roman Catholic religious commissions for the rest of his career. Slaby eventually designed three dozen known buildings, which, until now, have remained underappreciated. Looking closely at his work reveals an idiosyncratic use of modern and historicist styles and astoundingly high levels of craftsmanship and finish, offering lessons in creative interpretation that remain relevant today.

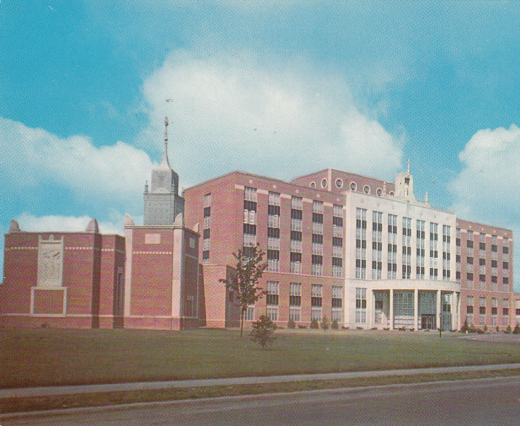

Slaby’s complex modernist pedigree is evident in his earliest commissions, many of which were Catholic schools. His work of the 1930s and 1940s was influenced by the Brick Expressionist movement in Germany and architects like Hans Poelzig, Fritz Schumacher, and Dominikus Böhm, who explored the material’s structural and ornamental possibilities. Slaby was also influenced by the Prairie School architect Barry Byrne, himself a designer of progressive Catholic churches. Lastly, select elements in Slaby’s work seem to derive from Frank Lloyd Wright, which may have been specific client requests.