ARCHITECTURE AND SOCIETY: WHITE ARKITEKTER AND SWEDISH POST-WAR ARCHITECTURE

by Claes Coldenby

Edited by Theodore Prudon and Eduardo Duarte Ruas

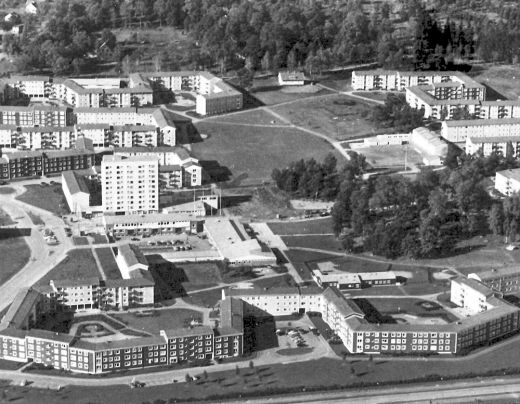

During the 1950s the Swedish building industry became unusually large-scale for a small country. Large clients, mainly public agencies, were supplied by large builders, given control of the process, and large architects’ offices, trying to cope with this. This was the context in which the firm White Arkitekter started in 1951. The history of the architecture in Sweden can be traced in the work of the firm in the following decades.

“Before maybe the architect’s relation to his employees was that of the master and the pupils. Now team work is a key concept for modern architecture,” Sidney White claimed in 1953. A large office, a strong belief in evidence-based knowledge and a model of employee ownership was his idea of a modern architecture. The legacy from the founder has been sustainable. Today White Arkitekter is Sweden’s largest office with more than 900 employees.