Primary classification

Education (EDC)

Secondary classification

A3. Press Release from Princeton University Department of Public Information

Terms of protection

Not currently protected

How to Visit

Private university building

Location

Prospect Avenue & Washington RoadPrinceton, NJ, 08544

Country

US

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Designer(s)

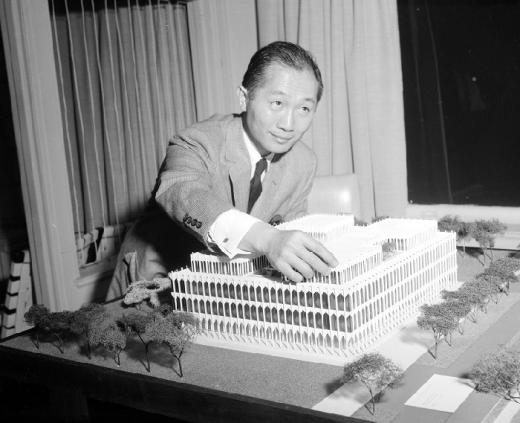

Minoru Yamasaki

Architect

Nationality

American

Other designers

architect(s): Minoru Yamasakilandscape/garden designer(s): Minoru Yamasaki (Scudder Plaza)other designer(s): James Fitzgerald, “Fountain of Freedom,” the water sculpture in Scudder Plazaconsulting engineer(s): building contractor(s): Turner Construction (relocation of original Woodrow Wilson Hall). William L. Crow Construction Company (construction of Robertson hall)