Before neon signs with trendy sayings were popping up in hipster mac n’ cheese bars, before old motels were being revamped into $300/night luxury experiences, before ruin porn proliferated on Instagram, there was the Society for Commercial Archeology. In 1976, almost a decade before he would go on to publish 1985’s influential Main Street to Miracle Mile, the first serious exploration of roadside architectural typologies, how they progressed over time, and the influence of the automobile on their design, Chester Liebs chaired a meeting at the University of Vermont, where he ran the Historic Preservation program, on the future of auto-oriented commercial architecture of the 20th century. Just a decade after the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, it was a topic many in his field turned their noses at, preferring the odor of musty colonial mansions to that of greasy fast food joints.

The Society for Commercial Archeology: An Almost Serious Look at Roadside Architecture

Author

Jeremy Ebersole

Affiliation

Board Member, Society for Commercial Archaeology

Tags

But people showed up. Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour’s Learning From Las Vegas had opened the door just a few years earlier to a scholarly appreciation for commercial architecture that would lead directly to Postmodernism, and waves of 1950s nostalgia was starting to simmer in the popular media (Grease or Happy Days, anyone?). Liebs’ meeting invited “anyone with a sincere interest in the study of the automobile-generated built environment” to attend his initial gathering and attempt to coalesce this building zeitgeist into something concrete. The group of 40 or so historians, curators, diner buffs, planners, architects, and students who showed up were an against the grain bunch who believed the rapidly disappearing commercial buildings of the 20th century roadside that the masses were starting to rediscover deserved the same kind of scholarly attention and preservation efforts as their older, fancier, dare I say more elitist architectural kin. This was a rabble-rousing bunch who believed 20-year-old buildings designed to get motorists out of their cars to worship at the altar of consumption had as much value as presidential birthplaces.

They wanted to better understand who else was thinking about these topics and how to build a broader coalition. After debating terminology, discussing the challenges of preserving buildings often designed to be temporary, and emphasizing the need to educate property owners on the value of what they had, it was decided that the time was right for a new organization to form to bring roadside scholars and preservationists together to carry the torch forward. Taking inspiration from the recently formed Society for Industrial Archeology, the group met in Boston the next year with Liebs as president for the first annual meeting of the Society for Commercial Archeology, a name that references archeology as the orderly study of objects from the past and their changes over time (in this case above ground buildings), in order to better understand the world of those objects’ creators and its relationship to us today.

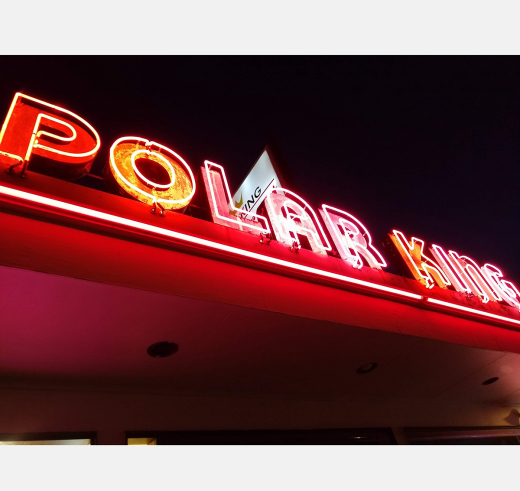

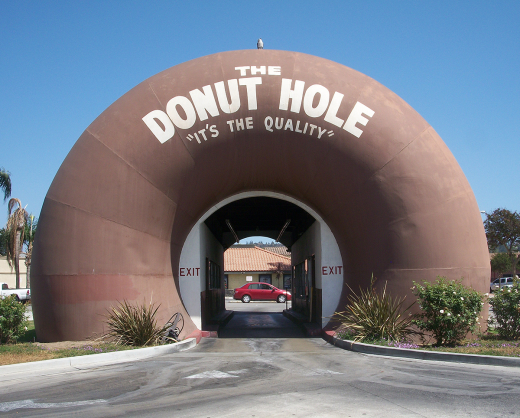

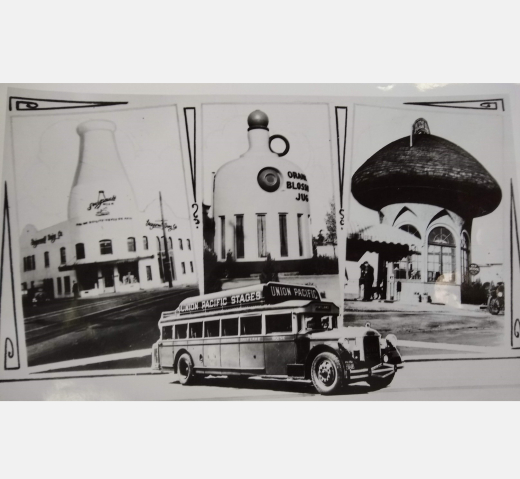

The world of commercial archeology that the SCA was created to explore, celebrate, and preserve goes beyond simple nostalgia. While the study of the unique built environment of consumption brought about by the 20th century rise of the automobile may seem like a niche topic, it in fact embodies the architecture that we interact with most often. It is the study of the places that make up our day to day lives: the restaurants we eat at, the lodging we stay at, the gas stations we stop at, the theaters we watch movies at, and the signs that point the way. Commercial archeology is the study of the fun parts of everyday life – from Googie angles to flashy neon signs to mansard-roofed restaurants and beyond.

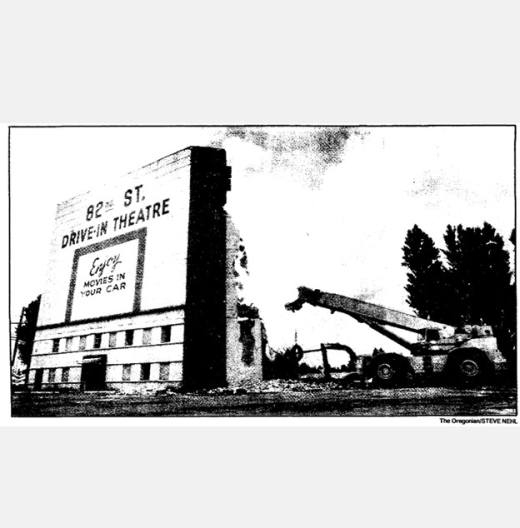

As today’s world turns away from the car and returns to earlier walkable, bikeable, neighborhood-oriented design patterns, the effect of the automobile on the American landscape remains unprecedented. A brief look at one particular road in Portland, OR, could be a microcosm for the rest of the country. Sandy Blvd., which is featured in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History’s “America on the Move” exhibition, began its life as a foot trail frequented by the native people of the Willamette Valley. Because this pre-existing trail had already been cleared by the period of European settlement in the Portland area enabled by the Oregon Trail, it was a natural choice for use as a farm supply road connecting the eastern farmlands to the core of the city. As streetcars gained prominence, the road served as a primary route for this new transportation method in the early 20th century.[1] In 1913, the road was paved, streetcar tracks were doubled along much of the length, and the road became a boulevard, reflecting the beginnings of the slow but steady transformation of the road from a streetcar suburb to an automotive strip.[2]

Automobiles continued to grow in popularity, and “everyone in Portland wanted to buy an automobile in the 1920s.”[3] By the middle of the prosperous decade, the 80 dealerships in Portland were selling 40 cars a day and ownership grew from 36,000 registered vehicles in 1920 to 90,000 by the time of the stock market crash nine years later.[4]

The effect of the increase in automobiles on the development of Portland was enormous, and by the mid-1920s auto-oriented business began to cluster, having moved away from earlier outposts closer to the city, and Sandy became a destination for the region for shoppers seeking a wide variety of goods. It was the long, narrow shopping mall of its day, each business trying to outdo its neighbor with glowing neon signs and even a number of examples of mimetic architecture, letting drivers know for example that shoes were available inside by building a store shaped like a shoe.

Automobiles and the businesses that served them allowed the city to expand during this time period into the space between small towns and streetcar “fingers.” By the 1940s, the newer suburban homes being constructed all had the option for a garage, and new building types catering to automobile passengers flourished. The automobile fundamentally altered development by allowing personal mobility, low-density living, and decentralization. Because they now had cars that could get them virtually anywhere quickly, motorists didn’t need to crowd together in cities and could live farther away. The concept of central hubs within neighborhoods, where consumers would take a streetcar into a walkable area to shop and recreate, began to give way to linear nodes, where consumers would drive along an arterial road and park at each individual destination. This transformation was made possible by the automobile and led to the decentralization of both settlement and commercial activity and the outward growth of cities along these linear strips. Businesses – including many new business types such as drive-ins and shopping malls – flocked to these ever longer arterials, always trying to balance low land costs in rural areas with a population large enough to sustain operations. The car, however, allowed the radius of potential customers to be much wider than it ever had been in the past. In short, during the post-war period “there was a redirection in basic attitudes about the structure of communities. In general, the era of densely packed buildings oriented to the street, with small blocks as a grid, gave way to larger land units defined by major arteries…The prerequisite for this type of development was the car, plus large areas of inexpensive land near population centers.”[5]

The most dramatic change for Sandy, however, came as a direct result of its popularity. The congestion of Sandy Blvd. paved the way for its replacement, and as wartime technologies allowed for the development of limited-access truck-proof roads, the desire to design traffic arteries strictly for speed of transit led to the transformation of older arterials like Sandy nationwide. Sandy was the first road in Oregon to be bypassed by an expressway when Interstate 84 opened in 1955, transforming the boulevard into a secondary road and cutting the traffic many businesses depended on considerably.[6] Today, Sandy remains a collection of early to mid-20th century commercial buildings cutting through the city, many of its large neon signs long since turned to plastic, a reminder of the earliest influence of the automobile on the streetcar suburbs it replaced and the effect of the freeway bypass on its former prosperity.

It is these types of typologies and explorations to which the SCA continues to turn its attention 44 years after its founding. The SCA has evolved over the years into a unique combination of serious scholarship, fun-loving appreciation, and active preservation support. Conferences and tours continue to be held annually, combining academic paper presentations with regional architectural tours, and an abundance of diner food. Since the onset of the pandemic, monthly Zoom presentations cover topics from ghost signs to Green Book sites to the history of shopping malls. The SCA has also continuously produced printed publications, today consisting of the quarterly SCA Road Notes newsletter and magazine-style biannual SCA Journal, which combine fun local 5 Faves articles with in-depth histories of tourist sites, all the latest news on the comings and goings of the nation’s neon signs, and much more.

As “America’s Roadside Heritage Advocate,” SCA is thrilled to participate in the Docomomo US annual theme of Travel & Leisure. What follows are two articles from past SCA Journals: Joanna Dowling’s 2008 study of Interstate rest areas and Lyle Miller’s 2020 look at the evolution of motel rooms. If you like what you see and want to join the motley crew Chester Liebs founded with a few brave iconoclasts all those decades ago and dive with us into our exploration of the bewildering, evocative, and always fascinating world of commercial archeology, just drive your browser over to the SCA website and cast your vote for the belief that a golden arch is just as important as a Roman one.

Notes

- Bart King, An Architectural Guidebook to Portland, 2nd ed. (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2007). Portland Bureau of Planning, Sandy Boulevard Commercial Corridor Retail Market Analysis.

- Love Portland Group at Hasson Company, Realtors, “Exploring the Roseway Neighborhood” (blog), November 3, 2017. Portland Bureau of Planning, Sandy Boulevard Commercial Corridor Retail Market Analysis.

- Carl Abbott, Portland: Planning, Politics, and Growth in a Twentieth-Century City (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983), 93.

- Ibid.

- Steve Dotterer, et al., “East Portland Historical Overview & Historic Preservation Study,” City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, March 2009, 39.

- George Kramer, The Interstate Highway System in Oregon: A Historic Overview, May 2004, prepared for the Oregon Department of Transportation.

About the Author

Jeremy Ebersole serves on the board of directors of the Society for Commercial Archeology and is Executive Director of the Milwaukee Preservation Alliance. He completed his master’s thesis for the University of Oregon’s Historic Preservation program in 2020 on regulations, incentives, and advocacy tools being utilized around the country to protect existing neon signs and the civic value of their preservation. Follow him on Instagram @jeremytheebersole.