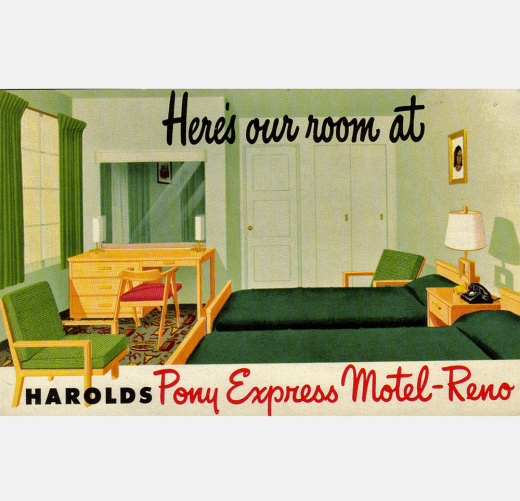

The sign beckons you, the building interests you, and the office welcomes you, but the room itself defines most of your motel lodging experience. It is here that the traveler sheds the stress of the road, seeking relaxation and slumber. The success, or lack thereof, of this effort determines the enjoyment of your stay.

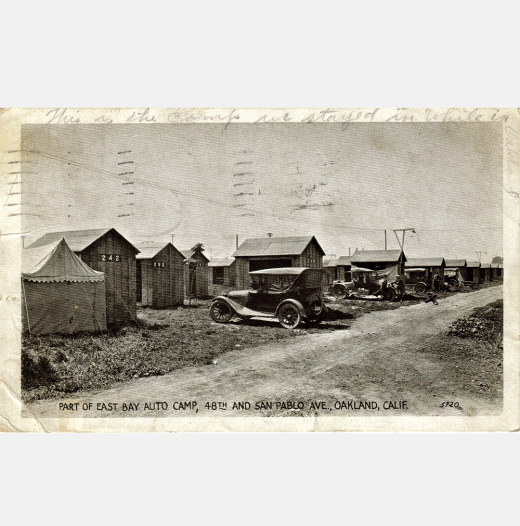

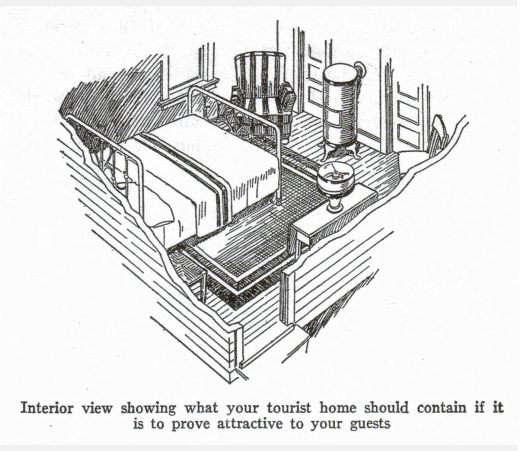

Early on, travelers were just happy with a roof over their heads and a bed lifted off the ground. Utilitarian conditions were acceptable, as the goal was to comfortably sleep through the night to hit the road the next morning. Although travelers were sometimes required to bring their own bedding, a crude cabin beat setting up a tent in the rain.

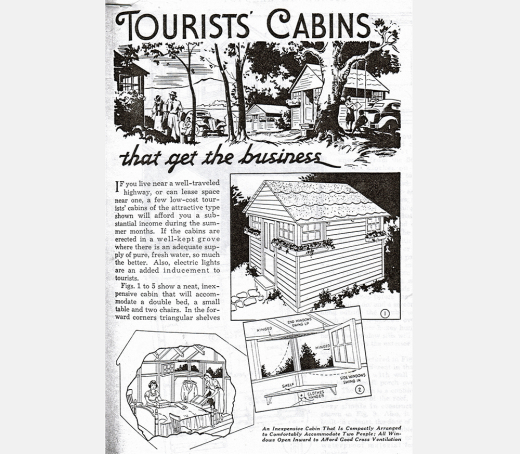

A property owner along a busy highway, with an investment of time and money, could start in the auto camp business. Popular Mechanics magazine provided some guidance with their July 1935 article, “Tourist Cabins that get the Business.” The three-page story explained the construction, while the illustrations showed dimensions and layout. In a 12x10-foot, 2x4-frame cabin, there was space for handmade furniture, including a bed, two chairs, a folding table, and a wall-mounted cabinet.

The traveler felt at home because these were standard furnishings of the era. By the 1950s, however, the motel room offered luxuries perhaps not found at home. Now there was a chance to enjoy wall-to-wall carpeting, Hi-Fi music, and later, color television. The day’s stress could be eased in a few minutes on a Magic Fingers bed for 25 cents.

A room too hot or too cold could negate all efforts of providing an enjoyable environment. Before air conditioning was available, occupants had to rely on Mother Nature for cooling. Windows placed on opposite walls could capture cool evening breezes. Cross ventilation was both a marketing ploy and a concept. Screens on doors and windows assured that insects were not guests. Steam heat provided a comfortable and cozy environment in the winter. As technology improved, motel units could offer individually controlled electric heat and refrigerated air conditioning that helped to assure a pleasant stay, as far as temperature, anyway.

A Good Night’s Sleep: The Evolution of the Motel Room

Author

Lyle Miller

Tags

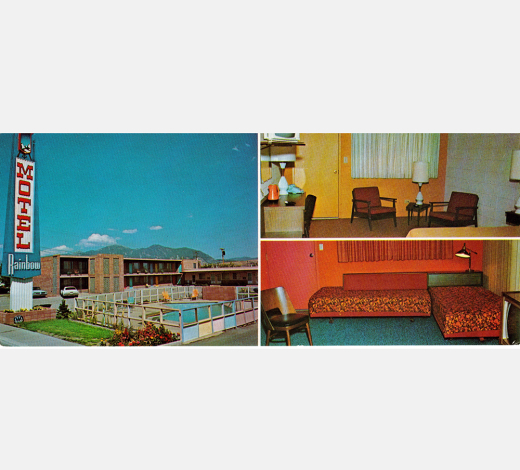

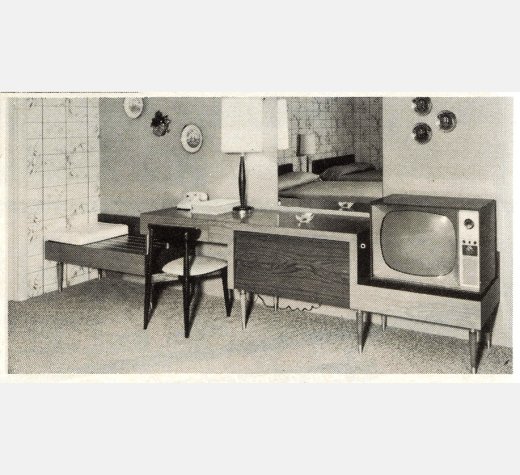

The room became more specialized, if not standardized. The March 1950 issue of Architectural Record dedicated more than 20 pages to the study of motels, their construction, and furnishings. The publication suggested that a typical double room should provide two double beds, a night table, a combination vanity/desk with mirror, and two blanket drawers. A small home-like closet could be more efficiently replaced with built-in shelves and "storage walls." Architectural books offered measurements for countertops and door openings as well as lighting levels.

Room furnishings evolved from separate individual pieces to specially constructed, multi-function, built-in units. Bed headboards attached to the walls extended out to include bedside tables with lamps. Components such as a desk, small dresser, television stand, and luggage rack formed a unit that spread from the front door to the bathroom wall. Here, the functions of bathing and dressing were divided. The toilet and tub were in a separate room with built-in sink and counter, clothes hangers, and a bench located behind a partial wall.

Bath and toilet facilities became more important over time. Restrooms that were shared by all guests were a hold-over from the auto camp era. In the movie, It Happened One Night, Claudette Colbert is shown waiting in line with several other women at Dykes Auto Camp to use the restroom. As the demands and expectations of travelers changed, so did the facilities. The term "Strictly Modern" in advertising generally referred to private bathrooms in each room. Sometimes the motel’s attached garage would be enclosed and turned into an interior bathroom, including bathtub, shower, or combination of both.

Cleanliness is indeed next to godliness for the traveler, and many motel owners took to heed. Early advertising offered that units were cleaned and renovated after each stay, and some were even “fumigated daily.” The use of ceramic tile, plastered walls, and washable materials assured the room could be adequately cleaned.

The road that brought the traveler to a motel could, through traffic noise, keep the traveler awake at night. Rental units at the back of the lot, and away from traffic, were the best bet for quiet. But other travelers could be a nuisance. Individual cabins and cottages allowed for a buffer between units, but multi-unit buildings did not. A line in the popular song "Lincoln Duncan" bemoans, “Well, I’m tryin’ to get some sleep, but these motel walls are cheap.” Extra insulation or masonry-dividing walls offered some relief but were not common.

One way to drown out neighboring noise was to make some of your own—and be entertained. In-room radios provided music and the latest news. Some owners charged for this pleasure with coin-activated electronics. Others saw this as an added value to the basic room rate, as was Hi-Fi and “piped in” music. Television became more available in every community, and motel owners understood this. A “TV lounge” initially provided a place to enjoy this emerging technology, but patrons soon sought individual room units with 21-inch screens. Color televisions came into vogue after more programs were broadcast in this medium.

Of course, the television may have to be turned down to use the direct dial room telephone. Previously only available in the lobby or a booth on the edge of the parking lot, the phone was a link to the outside world. Rather than bother with the front desk to place a call, travelers enjoyed the convenience of dialing, on a rotary dial, their calls themselves. A small red light on the phone indicated when a message was waiting at the office.

Room sizes might be kept to a minimum, but the overall complex's public spaces could serve as an extension to the room. Chairs or a sofa and table sharing space in the office provided a place to read the local paper or wait for visitors. An adjoining recreation room helped the children burn off energy playing ping pong or shuffleboard.

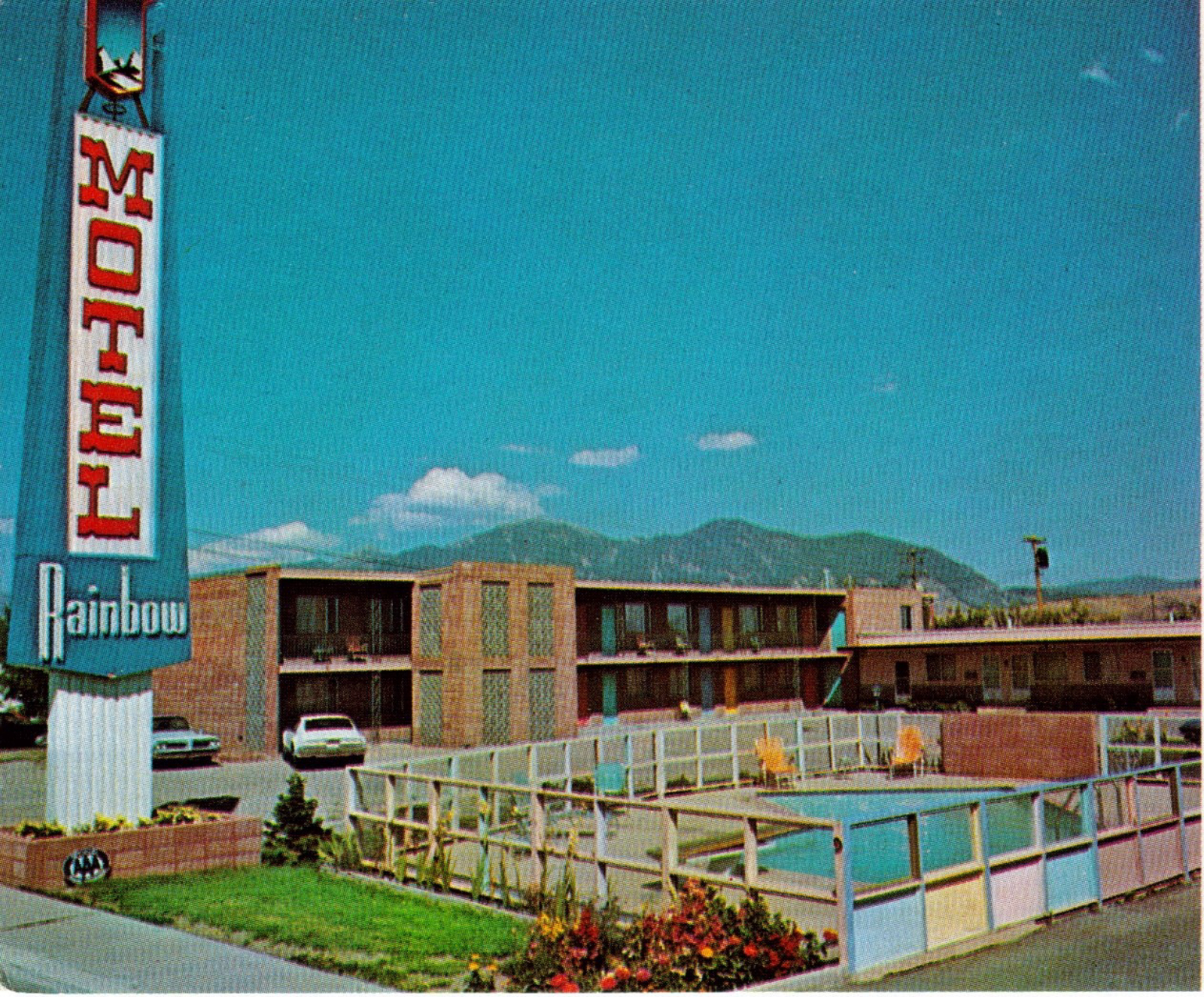

Later, terraces, and balconies on upper levels expanded guest quarters out the door and provided a place to lounge and view the scenery – be it nature or human. Especially popular in warm climates, the swimming pool offered great entertainment and therapeutic value. Some were part of the business plan from the start, while others were retrofitted into existing facilities. Located upfront, by the highway, the pool allowed passing travelers to see the fun and relaxation for themselves, and those in the latest swimming attire to be seen.

The 1935 Popular Mechanics cabins were utilitarian with small windows and doors, designed as a shelter for the night rather than a vacation destination. As automobile tourism matured into a thriving business, motel owners, particularly those in scenic destinations, looked at accommodating the long-term desires of vacationing travelers.

“Picture windows open onto a restful rugged mountain vista’” bragged one Colorado cottage court, while another advertised, “In our new motel units, glass doors open to a riverbank terrace." Even if the view wasn’t that good, sliding glass patio doors and large expanses of glass mimicked ideas found in design magazines. Full-length drapes could shut out the scenery while letting in filtered light and allow for some privacy.

Businesses that previously supplied hotel rooms found a new market outfitting motels. The use of Simmons and Beauty Rest mattresses became a selling point. Companies also offered durable and sturdy metal furniture, either as individual pieces or entire room settings. The Franciscan Furniture Manufacturing Co. of Albuquerque, New Mexico, provided furnishings, bedding, flooring, and draperies. Their color catalog inspired many motel owners from local Route 66 on to Arizona and California.

Motels evolved from simple, owner-built cottages to large, well-financed, and possibly architect-designed complexes. Prevailing trends in decorating found their way into the rooms and furnishings, as did local motifs. The design and furnishings of the rental room were just as important as the exterior presentation.

As chains and franchises developed, so did their corporate images. The Holiday Inn chain chose simple furniture painted in blue or gray and advertised “no surprises” so that a room in Dallas looked just like one in Denver or Des Moines. On the other hand, Best Western announced that no two Best Western Motels were alike, and invited you to “Discover the delightful difference yourself.”

A stop at an Interstate highway exit today provides the same (though dependable and predictable) lodging options that can be found at another exit 500 miles away, right down to the desk and lamp. So, it becomes a pleasant “surprise” when a traveler stumbles upon a truly unique and out of the ordinary experience, where they can “discover the difference” for themselves.

About the Author

Lyle Miller was born in Denver and earned a bachelor’s degree from Colorado State University-Pueblo. He was a retail clerk, construction worker, and computer operator before recently retiring after 24 years with History Colorado and the state preservation office. Lyle is currently restoring his vintage vehicles and adding more collectibles to his impressive basement museum.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of SCA Journal.