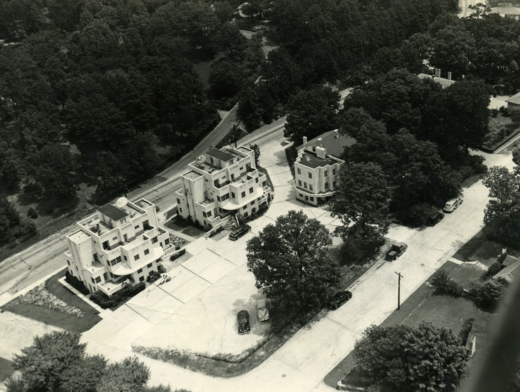

As the sun was setting on a February 2014 evening, the oldest wing of the four-building Majestic Hotel complex went up in flames. The suspicious fire that engulfed the beloved 1902 building set the stage— despite the stable condition of the handsome postwar modernist additions and 1924 brick wing—for the eventual demolition of the whole complex. Shuttered since 2006, the slightly curved 1962 Lanai Tower wing once formed an important focal point to the northern terminus to Central Avenue, the main drag running through downtown Hot Springs, Arkansas. A year later, on Christmas Eve, one could witness bulldozers ripping through the ca. 1959 Kings Inn, one of two motor court complexes straddling Central at the opposite end of downtown, once forming a gateway that transitioned between the central district and decentralized developments spreading southward towards the 1904 Oaklawn Racetrack. Both hotels were designed by local architect Irven Granger McDaniel, the younger member of the notable father-son duo and a World War II prisoner of war who, it is said, was the inspiration for The Great Escape character played by Steve McQueen [1]. Both had been heavily modified, the former Kings Inn (ultimately a Best Western Express Inn) quite unrecognizable by its final act.

Spa City Modernism: Postwar Hotels in Hot Springs, Arkansas

Author

Michael Grogan

Affiliation

Kansas State University, AIA Kansas

Tags

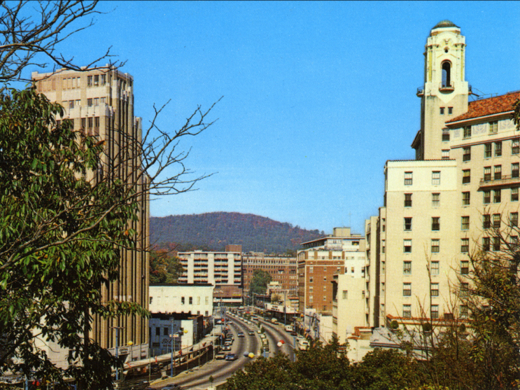

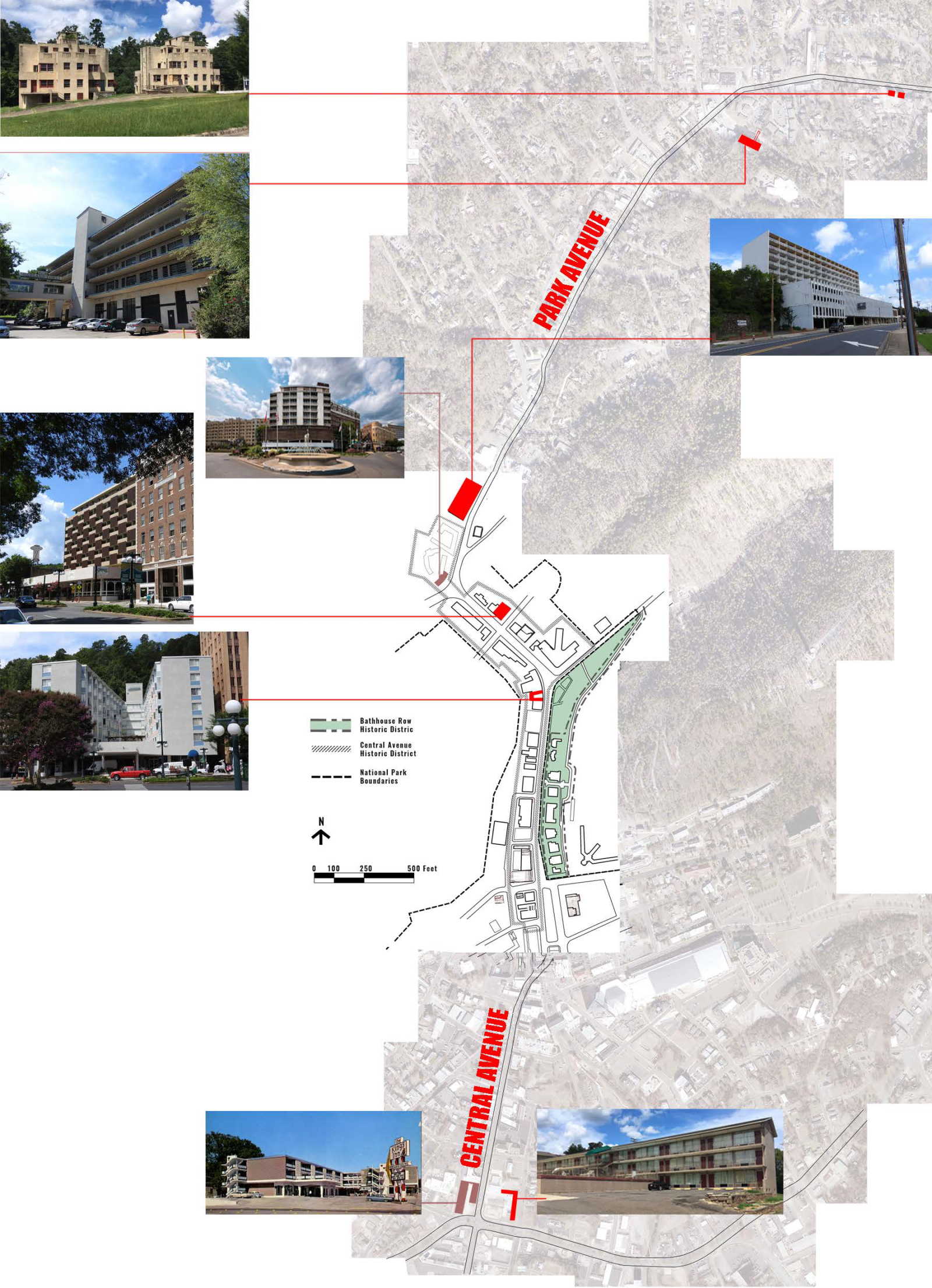

Despite such recent losses, Hot Spring’s downtown core and Park Avenue (Highway 70) approach road hosts several elegant modernist hotels sprinkled throughout an urban fabric typically touted for its historic Bathhouse Row, Arlington Hotel, and assortment of prewar buildings dating back to the 1880s, tightly hemmed into a picturesque valley of the Ouachita Mountains. This group of hotels, some undervalued and threatened, represent the final phase of the dynamic, almost century-long trajectory of the Arkansas settlement which was once considered a top resort destination in the United States.

Map credit: Michael Grogan (base diagram plan by Mahruf Kabir)

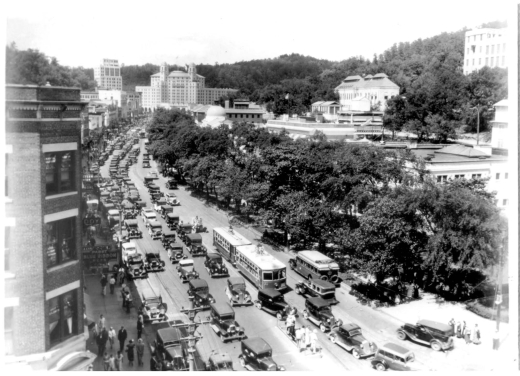

Hot Springs, AR, known as “Spa City” since the 1920s, uniquely resides within the nation’s first designated and federally protected Land Reservation (1832), later becoming one of the earliest National Parks (1921). Despite such protective classifications, accompanying stewardship, and the challenging mountain landscape, the town evolved quite dramatically and continuously between the 1870s and mid-1960s. The alleged curative benefits of the forty-seven springs and their endless supply spurred a flurry of dedicated bathing facilities for an ever-growing number of visitors to what became known as the “Nation’s Health Resort.” Hot Springs was also host to offseason professional baseball training, starting in the 1880s, bringing the likes of Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, and, as late as 1953, Jackie Robinson to town. More enduringly, the city cultivated a robust history of gambling operations, technically illicit but long-accepted as an integral part of the tourism- and revenue-generating lifeblood of Spa City. Thus, other notables such as Al Capone, Bugsy Moran, and “Lucky” Luciano might be sighted crossing Central within a more hospitable environment than they might have enjoyed elsewhere. These medical and recreational histories—often juxtaposing quests for virtuous health with conspicuous vice—underlay a city in dramatic transition for almost a century [2].

Accompanying this growth, bathhouses and lodgings evolved substantially, as did fierce competition manifesting replacement by newer facilities and often reckless proclamations positioning the springs as a panacea for all manner of ailments. Prior to World War II, Bathhouse Row and the increasingly luxurious hotels were joined by a series of 1920s and ‘30s motor court complexes—many designed in Art Deco or Moderne styles—spread along the main westward approach into town, as well as south towards the still-operating Oaklawn Racetrack.

After the war a series of modernist, full-service hotels were erected from the late 1940s to mid-1960s, capitalizing on a brief postwar boom that saw continued tourist interest in the restorative promise of the abundant mineral waters and tolerated-though-illicit gambling operations. Emboldened by the promises of the postwar economic landscape, hoteliers embraced an architecture of bold forms and expressive use of materials such as concrete and steel. These modernist additions offered a typological transition between automobile-centric motor courts and their older, traditionally urbane hotel counterparts.

The additions to the Spa City in this period introduced new aesthetic, constructional, and material developments, not to mention a certain optimistic disposition, typical of the architectural advancements of the era—keeping the city up to date within an important period in U.S. history. Through the efforts of the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, four of the five remaining hotels of significance are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, with three currently in use and two shuttered, awaiting future reuse.

Looming over Park Avenue at the historic main entrance into Hot Springs, the 1947 Mountainaire Hotel, a dynamically-modeled pair of four-story Art Moderne structures, once functioned as the city’s “smile” to approaching visitors [3]. The white brick-clad, clay tile structure with roof terraces and corner glazing units is the most threatened of this group of hotels, abandoned for decades despite a 2004 listing on the National Register (it has been purchased recently for proposed reuse) [4].

The original proprietor Alvin Albinson envisioned five identical structures, a scaling-up of the motor court typology that anticipated the larger modernist hotels soon to emerge within the downtown’s urban fabric. Only two structures were ultimately completed, likely making the hotel ill-positioned to compete with both the less expensive motor courts closer to downtown and the later, more programmatically sophisticated modernist counterparts.

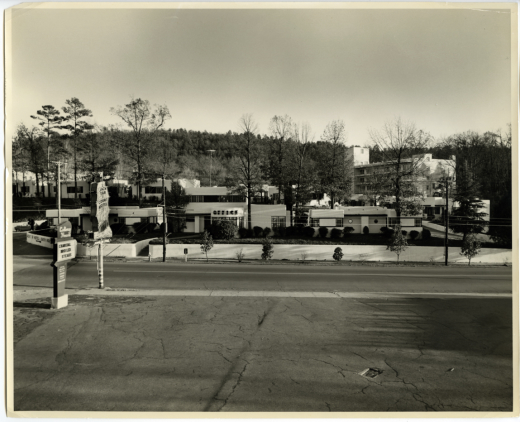

As the Mountainaire was opening, the younger McDaniel designed a large hotel close to the city center that, of this group, is perhaps the most strictly inspired by International Style tenets. The five-story slab with expressive, northwest-facing horizontal balconies, strictly framed by mostly solid end walls, position the Jack Tar Hotel as a seminal and serious example of modernism in the Spa City. Interestingly, this was an addition to a 1946 Art Moderne, single-story motor court complex across the narrow Oriole Street. A dynamic bridge once connected the two, now landing at the last remaining fragment of the former. Touted as “the most modern in the South with the finest construction to be found anywhere,” it was speculated that the ground floor, simply labeled “snack bar” in the permit drawings, harbored an illegitimate casino. Thus, this was likely the first postwar hotel complex designed to combine the two soon-to-be obsolete uses. After a few years accommodating the dwindling number of tourists, the hotel shut down in 1962 and was converted into a nursing home and more recently the Park Tower Apartments [5].

The Mountainaire and Jack Tar Hotels bridged a gap, stylistically and functionally, from the downtown luxury hotels and the motor courts to offer a hybrid typology for postwar tourists able to afford accommodations with wider amenities.

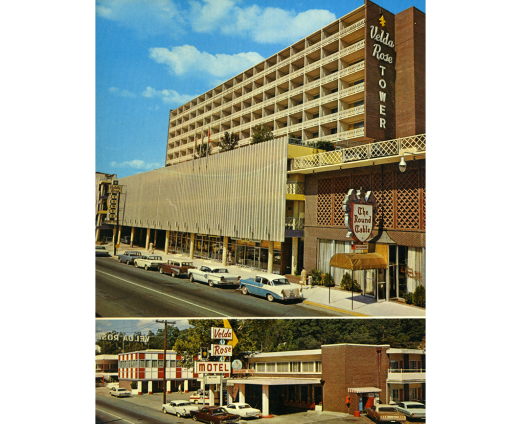

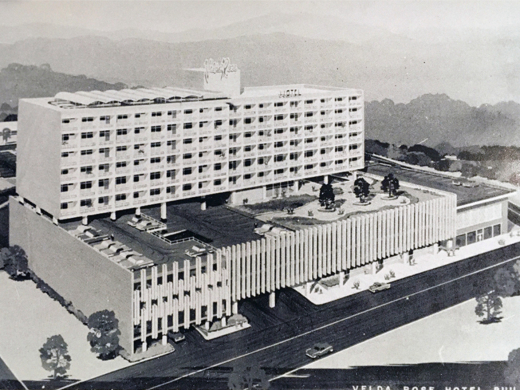

Once neighboring the 1902 Majestic Hotel before it burned in 2014, the 1964 Velda Rose Hotel has a forceful presence through scale and bold expression of its concrete frame. The hotel, renovated in 2001 but now vacant, has the misfortune of falling just outside the Central Avenue Historic District boundaries. The abandoned hotel offered a more exaggerated nod to automobile culture and the starkly white structure now lords over a context of emptied lots. At the time it was completed, the design sought to negotiate its transitional position between recent low-rise motor courts and traditional hotels that have since been lost. Formally the hotel operated at multiple levels: a dynamic interplay of horizontal slab and vertical eggcrate tower seized attention through the windshields of the approaching automobiles; the articulated parking podium contributed to the street-defining relationships offered by the ill-fated 1902 Majestic wing and 1900 Rockafellow Hotel that once resided across Park Avenue; finally, the recessed colonnade zone framed the lobby, retail, and automobile access at the pedestrian scale.

If the Jack Tar and Mountainaire Hotels occupy unencumbered, though topographically-challenging sites, the Velda Rose and razed Majestic attempted to combine the needs of the motoring tourist with traditional hotel amenities while nestling into a mostly now-lost urban fabric. Two other hotels further evolved this hotel type on Central Avenue, fortunately retaining much of their original context. They are deservedly listed on the National Register and have remained occupied for much of their history.

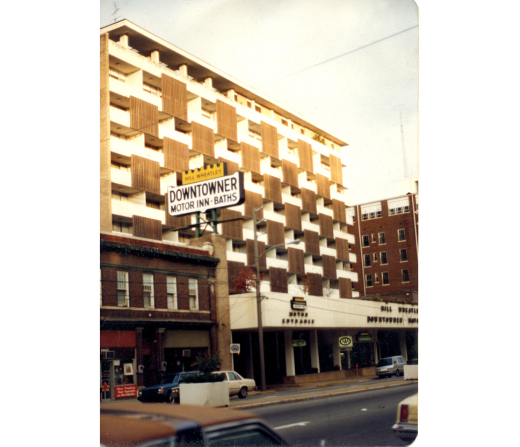

The ten-story, 1965 Downtowner Motor Inn Hotel and Bathhouse was commissioned by Hill Wheatly, a developer who at one point operated 36 of the 60 properties dotting the historic district. Wheatly selected notable regional architects, Howard Eichenbaum, FAIA and Nolan Blass Jr., FAIA, and thus a fortuitous congregation of personalities conceived this engaging ten-story, slab-tower design, set back from a street-defining podium. The lower portion supporting the pool terrace incorporates a slightly elevated porch, perhaps a nod to the Arlington Hotel’s wraparound veranda. The upper slab extends over the sidewalk, further engaging the passerby while visually holding in check the porch with entry, projecting glazed cylinder storefront, and the automobile access drive that hotels of this period necessarily incorporated. The rooms above extended out to individual balconies, partially clad with staggered fields of wood fins that add to the visual dynamism of both east and west elevations while filtering out sunlight and providing a sense of privacy. A rooftop penthouse caps the building, originally housing a banquet hall and, later, Mr. Wheatley’s private residence. Until recently the building continued to house hotel functions [6].

Across from the northern edge of Bathhouse Row, the Aristocrat Motor Inn was completed in 1963, deftly responding to its infill site along a bend in Central Avenue. Like the others, its base morphology negotiates automobile and pedestrian demands. Six floors holding 150 rooms (now subsidized housing) are extruded above a pool terrace-enveloping, V-shaped configuration. Formally this split resolves Central’s bend and the site’s axial position at the foot of Fountain Street; contextually the splay relates to the similar form of the neighboring 1904 Dugan-Stewart Building while the inner walls, composed of a series of saw-tooth window bays, offer a vertical cadence in dialogue with the striations of the soaring 1929 Art Deco Medical Arts Building to the north. The complexly-shaped, deeply carved podium frames an automobile drop-off, retail spaces, and lobby entry, attempting to negotiate the increasing expectations of car culture with the pedestrian realm. Listed on the National Register in 2017, the Aristocrat offers an elegant and bold response to a difficult infill condition [7].

One historian recently lamented the accumulation of “bland new buildings” into a fabric that, as the 1984 Central Avenue Historic District nomination form emphasized, was defined by “representative examples of a variety of building periods, types and styles that reflect the ever-changing needs and tastes of this spa community between 1880 and 1930.”[8] As that and other documents tend to dismiss postwar contributions, common perceptions cast these hotels and other introductions of modernism into the core as, at best, anomalies and, at worst, a destructive force on Hot Spring’s historic fabric. The depiction of downtown as a static “outdoor museum” composed of a traditional building stock that rose inevitably and organically around the abundant natural gifts possessed by the host valley is a common-though-simplistic interpretation, an underpinning of much recent tourism. In reality, Hot Spring’s century of growth was marked by unbridled competition that, coupled with occasional fires, fostered an environment of destructive cycles long predating the introduction of modernism. For instance, the 1892 Hale Bathhouse, the oldest of the fully-restored group, is also the fourth Hale Bathhouse erected on its site!

Though these hotels offer sometimes dynamic contrasts to this older context in scale, morphology, and materiality, befitting their modernist lineage, they all also evidence a considerate reading of their surroundings, a balanced interweaving with the urban conditions that preceded them. Their large scale is certainly a primary reason why all but one transitioned to different uses or were shuttered, but this is arguably not because of inherent architectural qualities; the rapid decline in the Spa City’s fortunes made them obsolete, in some cases before they reached the decade mark. By the mid-1960s, the purported curative qualities of the springs were increasingly second-guessed by the traveling public. That, coupled with the strict crackdown on gambling from 1967-on, dramatically altered the city’s fortunes as a tourist draw and, with it, the quick demise of most of the large hotel operations commenced. Though tourism has rebounded in recent decades, the nature of the current incarnation does not correspond with the ambitious building program of hotel and other facilities that defined the city for nearly a century.

Though some remain threatened, there are signs that perceptions are shifting towards an understanding of these postwar buildings as an integral component of the Spa City’s historical trajectory and, through considerate design, a positive contributor to a downtown that has once again reemerged as a desirable tourist destination.

Notes

- “Irven Granger McDaniel (1923–1978),” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, and according to Granger’s daughter, Diana McDaniel Hampo, in a discussion with the author on May 19, 2021. See also Callie R. Williams, “Arkansas Listings in the National Register of Historic Places: McDaniel and McDaniel, Hot Springs Architects,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 3 (Autumn 2019): 302-311.

- For Hot Springs generally, scores of books, essays, and photographic histories may be referenced. For a seemingly comprehensive history ominously produced right at the end of the city’s century-long trajectory of growth and transformation, see Francis J. Scully, Hot Springs, Arkansas and Hot Springs National Park: The Story of a City and the Nation’s Health Resort (Little Rock: Pioneer Press, 1966). The Garland County Historical Society (who advised that occasional Scully information and dates might not stand up well to scrutiny) also are a great resource, with many online and published resources such as their annual journal The Record. Executive Director Elizabeth “Liz” Roberts and others there proved especially helpful in providing input and refining my base information in preparation for this article. A recent book expands on the city as “America’s forgotten capital of vice,” see David Hill, The Vapors: A Southern Family, the New York Mob, and the Rise and Fall of Hot Springs, America's Forgotten Capital of Vice (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020).

- Michael Schwartz of Abandoned Arkansas recently stated, “to see that building go away, or get demolished, Hot Spring would lose its smile.” See “Hot Springs Hotel Getting Push for Restoration,” Fox16, November 9, 2020, https://www.fox16.com/news/local-news/hot-springs-hotel-getting-restored/.

- Ralph S. Wilcox and Bill Wiedourer, “Mountainaire Hotel Historic District, Hot Springs, Garland County,” National Register of Historic Places nomination form (approved February 11, 2004). It has been announced by Abandoned Atlas Foundation that a developer aiming to repurpose the complex for housing purchased the property on October 29, 2020.

- The 1962 date is listed in Sharon Shugart, The Hot Springs of Arkansas through the Years (Hot Springs, AR: Eastern National Parks and Monuments Association, 1996). Also see Elizabeth A. James, “Jack Tar Hotel and Bathhouse, Hot Springs, Garland County,” National Register of Historic Places nomination form (approved February 21, 2006). Anthony Taylor, AIA of Taylor/Kempkes Architects, P.A., the architects involved in the latest 2004 renovation, was generous enough to share their research-based “Determination of Eligibility” report supplementing to the hotel’s listing nomination form.

- Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, “The Downtowner Motor Inn Hotel and Bathhouse, Hot Springs, Garland County,” National Register of Historic Places nomination form (approved September 27, 2016).

- Callie R. Williams and Marshall Coffman. “The Aristocrat Motor Inn, Hot Springs, Garland County,” National Register of Historic Places nomination form (approved January 24, 2017).

- Quoted opinion in Ray Hanley, A Pictorial History of Hot Springs, Arkansas (Fayetteville, AR: The University of Arkansas Press, 2011), x. The listing nomination form: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, “Hot Springs Central Avenue Historic District,” National Register of Historic Places nomination form (approved June 25, 1985).

Sources

American Planning Association. “Central Avenue: Hot Springs, Arkansas.”

Eshelman, David J. “Bathing in Liminality: Soaking Up History in Hot Springs, Arkansas.” Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism 32, no. 1 (Fall 2017): 9-28. Accessed May 28, 2020.

Hill, David. The Vapors: A Southern Family, the New York Mob, and the Rise and Fall of Hot Springs, America's Forgotten Capital of Vice. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020.

Hill, Mary Bell. Hot Springs National Park. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Press, 2014.

Scully, Francis J. Hot Springs, Arkansas and Hot Springs National Park: The Story of a City and the Nation’s Health Resort. Little Rock: Pioneer Press, 1966.

Shugart, Sharon. The Hot Springs of Arkansas through the Years. Hot Springs, AR: Eastern National Parks and Monuments Association, 1996

Sutherland, Cyrus with Gregory Herman, et al. Buildings of Arkansas. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2018.

Williams, Kirby. “The American Spa: Hot Springs National Park.” Cloud 9 (Winter 2014). Accessed August 4, 2020.

About the Author

Michael Grogan is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at Kansas State University and the 2021 American Institute of Architects Kansas President. Michael once lived in the Hot Springs, Arkansas area and received his Bachelor of Architecture at the University of Arkansas, Fayettville. His research interests are focused on adaptations to and preservations issues with U.S. postwar architecture. His essay on Mies van der Rohe’s two additions to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston was recently published in Arris 31, the annual journal of the Southeast Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians and he authored “Plains Modern: Postwar Architecture in Kansas” published last December as part of the Docomomo US Regional Spotlight on Modernism series.