The following is an excerpt from the recently published book, Reglazing Modernism - Intervention Strategies for 20th Century Icons, by Angel Ayón, Uta Pottgiesser and Nathaniel Richards, which was awarded the 2021 Lee Nelson Book Award from the Association for Preservation Technology International (APT). The publication was recognized for being the most outstanding and influential book-length work on preservation technology.

Reglazing Modernism provides 20 in-depth case studies of Modern architectural icons in both Europe and the Americas. Focusing on interventions to their steel-framed glazing assemblies, the book offers a critical assessment of these, while also exploring emerging technologies that may offer higher performance in the future. Visit ayonstudio.com/book to learn more or to order a copy.

Preface

Modernism is the most defining architectural expression of the 20th century. The sheer quantity of Modern-era buildings world-wide is in itself impressive, especially considering that more build-ings were built in the 20th century than in all preceding ages com-bined.1 From the first late-19th-century examples whose stylistic vocabulary started to depart from Classical architecture to the most recognizable Modern works from the post-WWII period, Modernism transformed the built environment across the globe unlike any other previous period in civilization. The issues affecting these buildings today are increasingly at the forefront of discussions about sustainability, heritage conservation and building sciences, particularly in light of current global challenges like climate change and the need to increase energy efficiency of the built en-vironment.

Suffice it to say that, along with notable quantity and cultural significance, poor performance and limited longevity are also regular hallmarks of Modern buildings. More often than not, these deficiencies involve what is unquestionably one of the most character-defining features of Modern architecture—the exterior glazed enclosures. As a result, the need for interventions to address un-desirable conditions at the frames, glass panes and other components of Modern glazed assemblies—referred to in this book ge-nerically as reglazing—is ever growing. However, unlike historic materials and assemblies from earlier periods and other architec-tural expressions, whose intervention criteria has been well established for decades in both the academic and professional fields, there are no proven guidelines validated by time-tested practices that can help to evaluate the appropriateness of past interventions or guide practitioners on current or future projects directed at reglazing Modernism. This book is the first to compile and present critical assessments of a range of intervention approaches to reglazing Modernism. Its goal is to help to fill an informational and analytical void within the profession, and ultimately to help define best practices for intervening on Modern glazed enclosures.

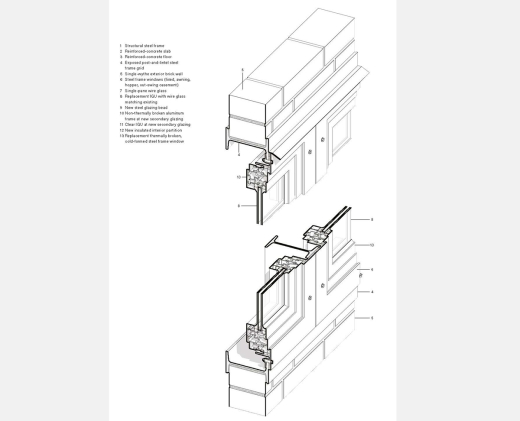

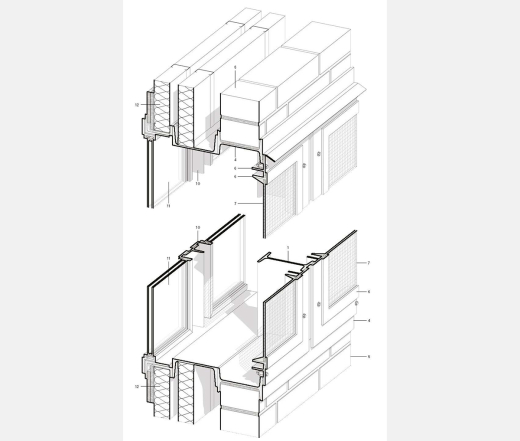

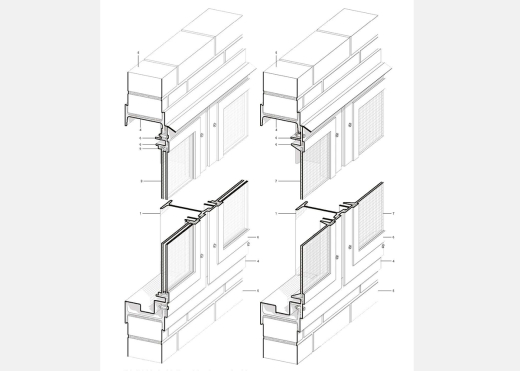

The research presented in this publication is based on the analysis of 20 case studies—nine in the US and eleven in Europe—that together exhibit a wide range of construction typologies and interventions on single-glazed steel frame curtain wall and window wall assemblies. Most of the case study buildings have been retrofitted within the last ten to 15 years in response to one or more driving forces, leading to different intervention approaches—broadly categorized in this book as restoration, rehabilitation or replacement. These categories, the interventions and their moti-vating factors—such as increasing energy performance or comfort requirements, safety and security concerns, changing functions, and reuse, or material decay, as well as stipulations of historic preservation and heritage conservation—are part of a general discussion in the Intervention Categories section that leads to the presentation of the case studies themselves. In each case study, the book highlights through research and illustrations how the glazed enclosures contribute to the cultural significance of each building, what the conditions were before and after the interven-tions and offers the authors’ opinions on the outcome.

With regard to the selection of the case studies, it was clear early on in the research that reglazing Modernism is far too wide a topic to address in one book. Several strategic choices were made in order to select representative case studies. While these are pri-marily explained in their own section preceding the case studies, the critical decision to focus mainly on steel frame Modern glazed enclosures is worth noting. There are a wide range of Modern glazed assemblies built with frames made of wood or other metals (like aluminum, bronze or even other types of steel, such as stain-less or weathering steel). However, the most commonly encoun-tered assemblies on low-rise, low-density, highly significant Mod-ern buildings are those built with mild steel. Clearly, research on the intervention approaches to other types of Modern glazed as-semblies is still needed, and we hope that this book may be only the first of its type in a series that can go on to explore the range of intervention approaches and issues unique to glazed assemblies made out of other materials.

The book concludes with sections summarizing critical findings and pointing to emerging trends derived from the analysis of the case studies. Topics where additional research and development is required are noted, as are high-performance systems that are becoming available in the marketplace as a response from the fenestration industry to the challenges posed by some of the inter-ventions presented in this book. Relevant bibliographic information is also provided so that readers can further explore each case study on their own. While we expect the analysis and criteria included in the book to be of use to both professionals and students, we hope that the graphic information and supporting 3D models will also be of interest to a wider audience.

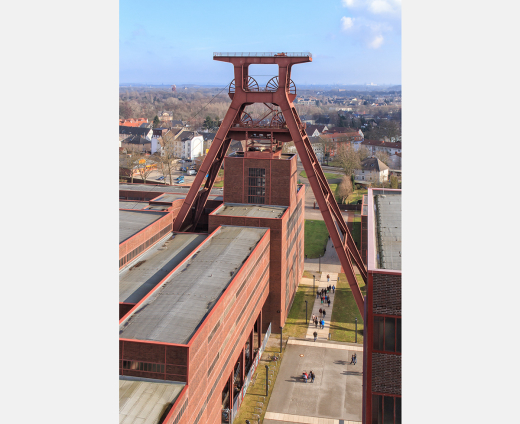

Case Study: Zeche Zollverein

Essen, Germany

Fritz Schupp and Martin Kremmer, 1932/1961