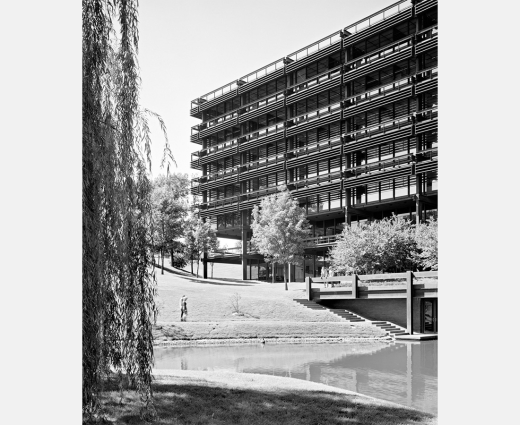

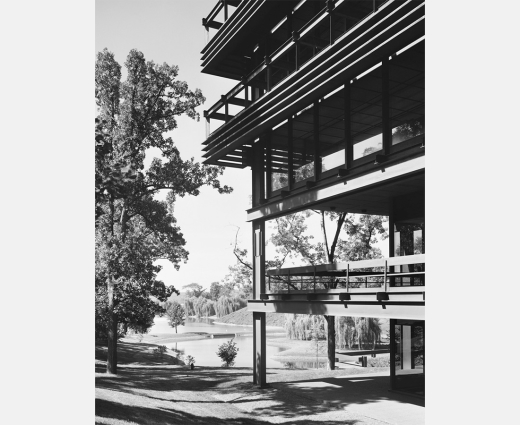

Postwar corporate campuses were an important proving ground for architects to demonstrate the core principles of modernist design: that form should follow function, and that the honest expression of building materials should put their inherent qualities on display. Because corporate campuses in this era were also seen as rural oases, set apart from their urban high-rise counterparts on large plots of land, landscape design played an essential role in the expression of place. In many cases, the architectural expression of a modernist corporate campus required that it borrow some drama from its surrounding landscape. And, in some cases, this meant bringing the outside in.

In this article, we examine three different modernist corporate campuses that feature true collaborations between architects and landscape architects. A key landscape design figure in the modernist era was Hideo Sasaki, who made a name for himself during the mid- to late 1950’s by collaborating with some of the most notable architects of the time. His collaborations spanned many different project types and scales, from single family residential to civic buildings and plazas to corporate campuses. Sasaki’s practice endures today; the firm he created still practices across the country and the globe and remains centered on its mission to integrate expertise across disciplines to achieve better design outcomes.

The ideals of an integrated design practice were shared among many prominent architects and designers in the modernist movement, including Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames, Harry Bertoia, Florence Knoll, and Ralph Rapson. Many met in academic settings, primarily while at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, establishing shared design principles and relationships that would spawn future collaborations among them. And when it came to selecting a landscape design partner, Hideo Sasaki was highly sought after for his collaborative spirit and design approach that seamlessly integrated nature with built form.