During the Docomomo US National Symposium in Detroit this past week, attendees had the unique opportunity to visit the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan. Hosted by General Motors and the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office, the tour not only allowed us to see the incredible architecture and design of Saarinen's corporate masterpiece but also showed the care and stewardship as the complex continues to age.

During the Docomomo US National Symposium in Detroit this past week, attendees had the unique opportunity to visit the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan. Hosted by General Motors and the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office, the tour not only allowed us to see the incredible architecture and design of Saarinen's corporate masterpiece but also showed the care and stewardship as the complex continues to age.

The excerpt below takes a look back at the vision that both Eero Saarinen and Harley Earl had for General Motors and how it redefined the image and perception of what the corporate campus could and should be.

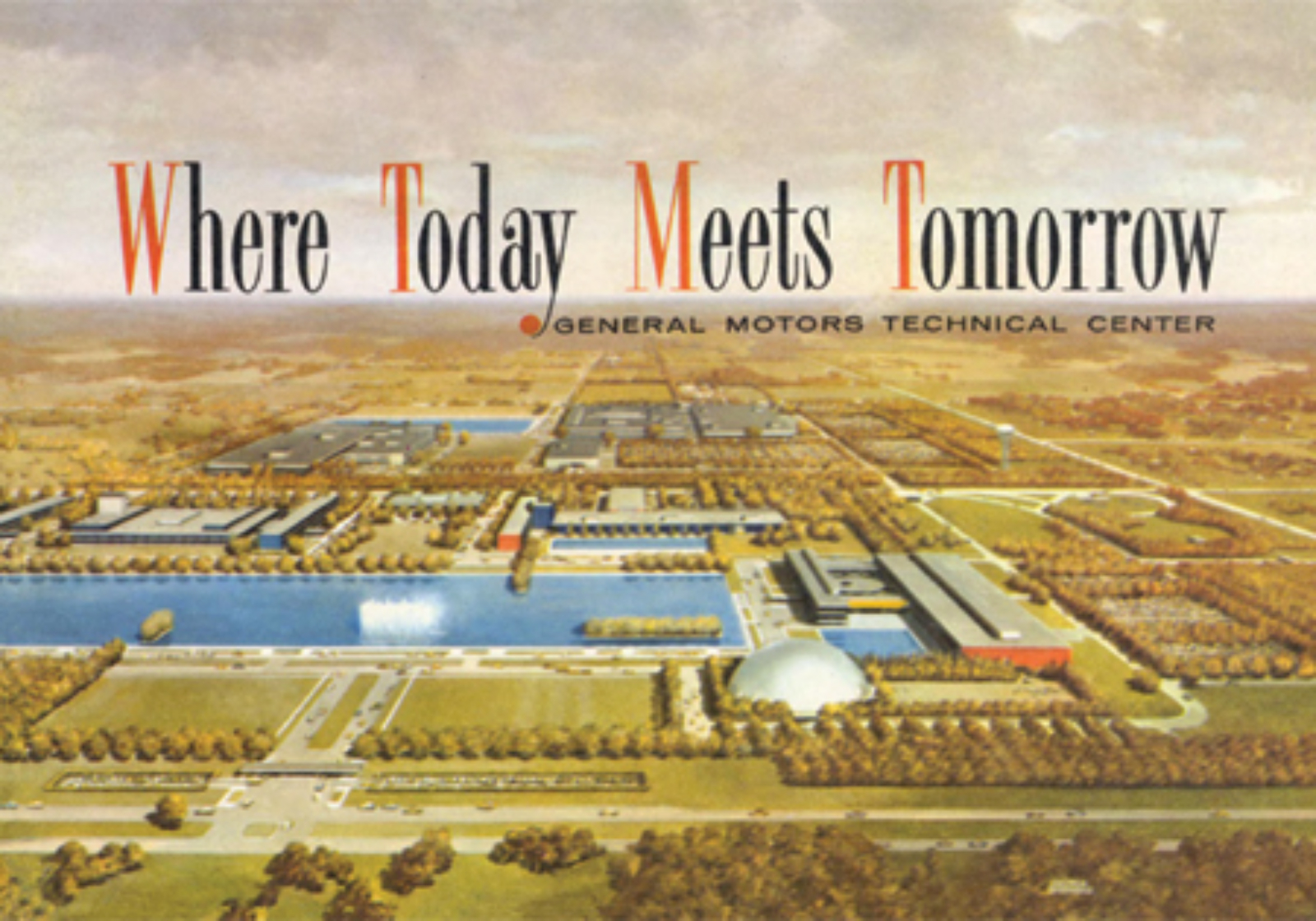

General Motors Technical Center, brochure cover. Credit: Eero Saarinen Collection, Yale University Library.

General Motors Technical Center

Saarinen’s first foray into this uncharted architectural territory, the General Motors Technical Center (GMTC) in Warren, Michigan, was a dazzling demonstration of what a glamorous American modernism could be.1The program called for the creation of a campus-like complex in which new ideas could be developed and tested, with new office suites, design studios, conference rooms, libraries, laboratories, test tracks, restaurants, and lounges available for some five thousand engineers, scientists, and designers. Many of the early renderings by Hugh Ferriss, who worked with Eliel and his son on the first phase of the project in 1945, showed the complex in night views, with bold, streamlined shapes and clusters of shadowy, muscular figures backlit by the glow of light that emanates from the enormous windows. Although the project would ultimately lose much of this robust (and rather dated) Moderne imagery as it evolved in the 1950s, it would remain unrepentantly stylish and theatrical, using choreographed circulation routes and vistas to highlight both the company’s automotive products and the modern American technology that made it all possible.

Situated on 320 acres of former farmland in the countryside twelve miles north of Detroit, the GMTC was composed of twenty-seven buildings arranged asymmetrically around an enormous rectangular reflecting pool. The scale of the complex was vast, intended to be experienced from a moving car, in a horizontal circulation pattern unprecedented in American corporate culture; this was just one of many such previews of things to come in postwar business.2Into this rural setting, landscaped by the prominent designer Thomas Church, Saarinen inserted key focal elements to serve as pivots or counterpoints, including a large stainless steel water tower that rose 140 feet. Strategically placed in its reflecting pool like a gigantic, high-tech version of the Carl Milles fountain sculptures at Cranbrook, and surrounded by a “water-wall” of jets by Alexander Calder, the tower helped to give the complex a “camera-ready” pictorial sleekness and an aura of shimmering luxury that delighted Saarinen’s clients and, predictably, created feelings of unease among critics.3

Left: General Motors Technical Center, Warren, Michigan, 1945-56. Night view detail, water tower, and pool. Credit: In Where Today Meets Tomorrow. Right: General Motors Technical Center: Styling Building stairs. Credit: Ezra Stoller © ESTO

With its rectilinear site plan and spare, flat-roofed buildings, Saarinen’s GMTC clearly owes a great deal to Mies van der Rohe’s well-known campus plan for the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago; indeed, this was the modernist lineage that most contemporaries recognized most readily. Nevertheless, the prominent Styling Dome, columnar exhaust towers, and planar reflecting pools at the GMTC also call to mind traditional Beaux-Arts planning devices, linking the project to more conservative efforts, such as the designs for the United Nations complex at Flushing Meadows by Wallace K. Harrison and his associates, as rendered by Ferriss in 1946.4This parallel is less arcane than might first appear, given Harrison’s, and the U.N.’s prominence in the field, as well as the widely shared objective among American architects in the 1940s of creating hybrid monumental imagery for public and institutional projects. By calling on such associations Saarinen sought to invest his project with monumental presence and a level of consequence not normally associated with American business and manufacturing.

More talented and more attuned to European modernism than most of his contemporaries, Saarinen went further and had greater success in his image-making, using a restrained historicism as a jumping-off place for the exploration of a complex mix of themes; indeed, the combination of a high-tech, modular system of construction - for which Saarinen, in consultation with GM’s engineers, invented new methods of using thin enamel panels and neoprene gaskets (like those used in car windshields) to hold the plate-glass windows in place - and the almost whimsical touches of handicraft, such as the brightly colored glazed brick walls, developed by ceramicist Maija Grovel at Cranbrook, point to a unique fusion of functionalism, artistry, and pictorialism that would become Saarinen’s trademark.5Here, for example, in addition to the influences of Mies and the elder Saarinen’s Cranbrook teachings (themselves and outgrowth of the sort of Finnish National Romanticism brought to life at Hvitträsk, 1901-3, the family’s country estate outside Helsinki), one can recognize something of the quirky California modernism of Charles Eames, with whom Eero had collaborated on Case Study House No. 8, Eames’s own home, and No. 9, a house for John Entenza, editor of Arts and Architecture magazine in the late 1940s.6Such embellishments as the gilded bronze screen by Harry Bertoia, another Cranbrook associate, in the restaurant, the enormous, freestanding Bird in Flight by Antoine Pevsner in front of the Styling Building, the numerous wall sculptures and murals by artists (among them many women) such as Buell Mullen, Gere Kavanaugh, and Gwen Creighton Lux that dotted the walls, or even the color-coded steam pipes of the powerhouse clearly indicated levels of artistry and luxury under of in such setting.7

Oldsmobile Rocket advertisement, 1956. Credit: General Motors LLC, GM Media Archives.

When the complex opened to the public, Life magazine ran an article describing it as the “Versailles of Industry.” The phrase was picked up by a number of journalists, perhaps as a result of suggestions by the publicity department.8Whatever the source, the catchphrase vividly communicated the company’s aristocratic self-image, and it underlined the message that, in democratic America, even company executives, and certainly the buyers of luxury GM cars, could live, work, and feel like royalty. One writer even went so far as to remark that the huge columnar exhaust vents of the Dynamometer Building were “as monumental as the stone pylons in Egyptian hypostyle halls of 1300 BC.”9Such comparisons were no doubt pleasing to both architect and client; although the GMTC was intended as a place in which “Today Meets Tomorrow,” and the company as a whole kept its focus firmly on creating both the products and the profits of the future, it was also significant that the architecture of the complex could hold its own with the great traditions of the past.10

Even with all that the architect was able to accomplish in the site plan and on the exterior of the buildings, it was the extraordinary interior spaces of the GMTC that made Saarinen’s project truly distinctive. In each of the principle lobbies, he placed dramatic staircases; these served, as he explained, as “ornamental elements like large-scale technological sculptures,” communicating each division’s own distinctive “personality.”11In the Research Building, for example, the staircase was a huge, open spiral of black polished granite and chrome-plated wire - recalling both Tatlin’s 1917 “Monument to the Third International” and Niemeyer and Costa’s Brazil pavilion at the New York World’s Fair - which contrasted boldly with the creamy, travertine floor and the rectilinear shapes of the lobby seating area.

Shimmering reflections and sensuous textures contributed to the theatrical scene, creating the unlikely but undeniable effect of ennobling the General Motors researchers as the descended to greet their waiting visitors or ascended to their studios. The experience was like a performance, and the spaces seemed to have more in common with the grand foyers of European palaces or opulent opera houses than they did with the mundane waiting rooms of a Midwestern automobile manufacturer. Saarinen’s gift for creating such recollections, no doubt enhanced by his education in the Theater Department at Yale and his experience as a sculptor, guaranteed his success with clients.12

General Motors Technical Center: main display area of Styling Dome. Credit: General Motors, LLC, GM Media Archives

The staircase in the lobby of the Styling Building was a double flight, open on one side and set against a wall of dark blue-black glazed brick, that descended into a shallow pool of water. This staircase acted not only as a perfect backdrop for photographing new model cars for advertising spreads, but also as a stage on which fashion models appeared perfectly at home. Here, as in the nearby Styling Dome, where a perfectly proportioned circular disk of modulated light (manipulated by a high-tech rheostat) floated above the viewing area, transforming the cars into movie-stars or objects of veneration in a sacred space, the architects seemed to take their cue from Hollywood, with its aura not only of visual luxury ut also of glamour and make-believe.

The driving force behind these innovations was the legendary Harley Earl, vice president of the corporation since 1940, who had singlehandedly invented the Styling Section in the 1920s and in so doing had created a place at General Motors for design development that would propel the company to enormous profitability.13It was Earl who hired the Saarinens in 1945, and he remained a key member of the client committee throughout design and construction.14Born in 1893, Earl had begun his career as a designer in his father’s coach-making business in Los Angeles; he later specialized in custom bodywork, designing cars for Hollywood movie stars. In 1927 he was recruited by General Motors and moved to Detroit, where he founded the Art and Color Section (renamed the Styling Section in the 1930s), introducing a number of design innovations intended to appeal to popular taste by combining sensuous curving forms with new automotive technologies. The “dream cars” that Earl worked on over the course of his career, including the 1928 LaSalle and the 1937 Buick Y-Job, were legendary: they were long, shiny, fast, and sexy, and they brought the feeling of custom design, European sophistication, and luxury to the American consumer.

With Alfred P. Sloan, the president of the company, as his sponsor and protector, Earl made the Styling Section the key element in the corporation: he created a complex process of design development and critique, based on the use of clay models and full-scale mockups, which was intended to search out and replicate the subtle ingredients of popular desire. Earl understood that in a consumer-driven economy car designers had to study fashions in other sectors of the market; he respected the power of women as decision-makers in the home, and he hired them as designers of color and trim. At General Motors, where the slogan was “A car for every purse and purpose,” every employee was a critic and a potential customer whose opinion counted, and the various divisions competed against each other to present an appealing array of choices. As Sloan recalled, “ We were all window-shippers in the Art and Color ‘sales-rooms.’”15

Damsels of Design and Harley Earl, 1954. General Motors Media Archive, Petaluma.

Most important, Earl made General Motors into a company that understood the mysterious role that cars played in the American psyche not only as an object of desire, but as a key to freedom and a sense of well-being. He “wanted to design a car,” he said, “so that every time you get in it, it’s a relief — you have a little vacation for awhile.”16Under Earl’s leadership, General Motors offered its customers new colors, new upholstery styles, shinier chrome, and even “new styling features” like tail fins, which, “though far removed from utility,” as [GM president Alfred] Sloan put it, “seemed demonstrably effective in capturing public taste.”17Earl’s ideas about the complex ways that design communicated meaning, expressed emotions, and stimulated desire were clearly reflected in the architecture of the GMTC, just as Earl’s own powerful personality established the theme for the office that Saarinen created for him: like a Playboy pad filled with “gorgeous gadgets” and smooth, sensuous surfaces, it was a command post and an entertainment center that Earl oversaw from behind his custom-built cherry desk. His private dining room, visited by a reporter from Interiors in 1957, had a “sort of night club expectancy and intimacy” about it; with its black, dark blue, and silver color scheme and its table-side controls used to manipulate music, draperies, lighting, and even to summon the “waitresses,” it was a fantasy world befitting the man at the center of General Motors’ Industrial Versailles.18

Like Harley Earl, Saarinen was eager to produce buildings that made people look good and feel good - both literally and figuratively. Beginning with his earliest furniture prototypes he focused not only on the formal design potential of new techniques and materials but also on comfort and appearance.19His Womb Chair of 1948, for example, produced and sold by the Knoll Furniture Company (Florence Schust Knoll was also a Cranbrook graduate), was explicitly designed with these priorities in mind. “A chair is a background for the person sitting in it,” Saarinen wrote. “Thus the chair should not only look well as a piece of sculpture in the room when no one is in it, it should also be a flattering background when someone is in it - especially the female occupant!”20This approach, based on the notion that the chair, the person sitting in it, and the building were not separate entities but coordinated elements in a “family of forms” - his father had taught him to “always thing of the next larger thing,” he said - proved extremely successful in practice. The buildings and the furniture made the people who used them look and feel better - and they were grateful to the designer for that.21

Another reason for Saarinen’s success was his wife, Aline, an art historian, a critic, and a journalist who, following their marriage in 1954 (it was the second marriage for both), took over responsibility of public relations for the firm.22The couple had met when Aline was sent on assignment to Cranbrook by the New York Times to interview the architect and tour the nearby General Motors Technical Center, still under construction; their rapport was instantaneous and passionate.23In April 1953 Aline published an article entitled “Now Saarinen the Son,” chronicling Eero’s early career and achievements. This was just the first of many such testimonials that she would contribute (though often from behind the scenes) as Saarinen’s most enthusiastic booster.24

Aline was glamorous, sophisticated, and smart, and she wasn’t afraid to admit that she wrote for a general audience, albeit an educated one. With more than a hint of irony, the critic Reyner Banham called her “one of the grander dames of art journalism” (Aline was raised in a middle-class Jewish family in New York.”25She was comfortable in evening clothes and at home in front of a camera: following Saarinen’s death she would appear frequently as a television correspondent for CBS and as an art commentator for the Today show, and she never tired of making sure that her husband’s work was kept in full view of the public, bringing out a volume of his writings, Eero Saarinen on His Work, in 1962. While some observers among the architectural elite found such self-promotion unseemly, corporate clients had no such scruples about the business of advertising. Business was business, after all; the Saarinens were simply promoting their product, and they did so with energy and style.

About

Alice T. Friedman is the Grace Slack McNeil Professor of the History of American Art and Director of the McNeil Program for Studies in American Art at Wellesley College.

Notes