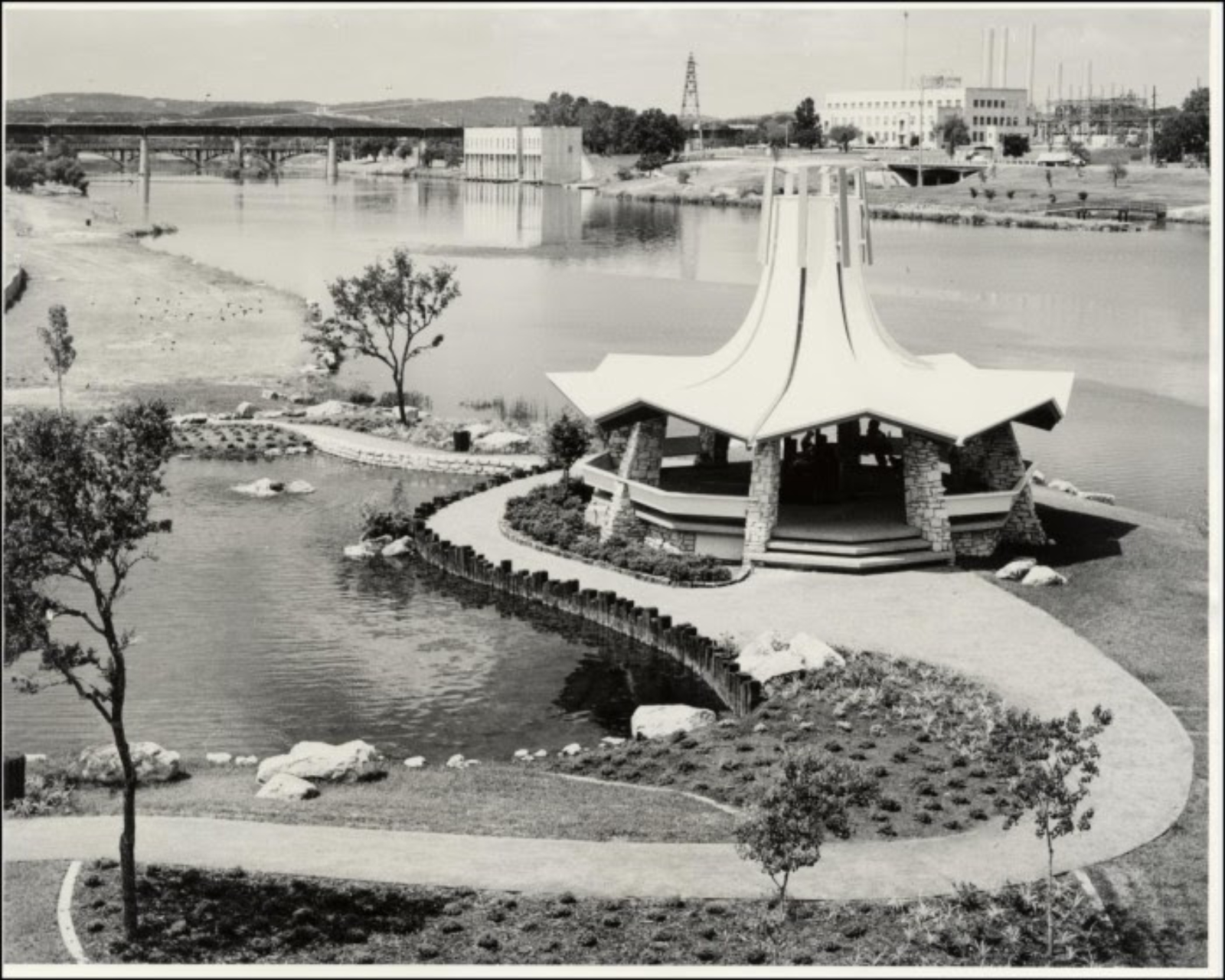

Take a stroll along the hike and bike trail of Lady Bird Lake and you’ll come across an inviting structure with a story significant to the lake that embodies the beauty of Austin. The Fannie Davis Town Lake Gazebo marks the spot of the beginning of the city’s efforts to improve the area through the Town Lake Beautification Project, inspired by Lady Bird Johnson’s national programs.

Fannie Davis Town Lake Gazebo

Author

Lori Martin

Tags

As First Lady of the United States, Lady Bird Johnson launched a beautification plan for Washington, D.C. and played an instrumental role in promoting the Highway Beautification Act of 1965. Upon the Johnsons' return to Texas, Lady Bird focused her efforts on Austin and the Town Lake Beautification Project. Before that time, little progress had been made to realize the lake as a welcoming recreation attraction for the city. Lady Bird’s project marked the beginning of the significance Town Lake would ultimately play in Austin’s cultural landscape.1

On November 9, 1965, the Austin City Council unanimously voted to approve plans presented by the Austin chapter of the National Association of Women in Construction (NAWIC) to undertake a project on the shores of Town Lake.2 In February, 1966, the Chapter released a statement announcing their plans to construct a gazebo on the lake. Gazebo, a term unfamiliar to many Austinites at the time, was often described as a band-stand type structure. The structure was to be a gift to the citizens of Austin from the NAWIC chapter and meant to serve as a lasting tribute to the construction industry.

The gazebo was the first structure built along the shoreline after the lake was created by the construction of Longhorn Dam in 1960.3 Initially formed as a reservoir to cool the Holly Street Power Plant, Town Lake, as it was named, began to be given serious consideration for its development as an asset to the City and its citizens. Although Lady Bird Johnson was not involved with the planning, fundraising or building of the gazebo, the project is associated with her national beautification initiative as First Lady.

In response to their interest in the Town Lake Beautification Plan, the Austin chapter of NAWIC decided to focus its annual construction project on a gazebo and first began planning and raising money for the structure in 1966. They originally estimated the project would take two years to complete, but that timeline was soon abandoned. The Chapter raised $6,000 to bring the gazebo to fruition, a four-year fundraising effort on their part. Local construction companies, material suppliers and workers contributed significant time, materials and expertise to complete the project, resulting in donations totaling over $30,000 in-kind.

The groundbreaking ceremony finally took place on Monday, July 1, 1968, with City Council members, city officials and other dignitaries on hand.4 At the time of the groundbreaking, construction on the “summer house” was expected to be completed by later that year. Ultimately, the work was performed in addition to the construction crews’ regular workload so progress was slow and tedious.5 The gazebo was dedicated on June 8, 1970.6 Decades of ongoing commitment to the project from the Women in Construction and the entire community reflects enormous civic pride during Austin’s early years of growth.

The architect for the gazebo was J. Sterry Nill7 (d. 2002). Born in 1928 in Chicago, Illinois, John Nill came to Austin in 1953 to enroll in the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture. He was an admirer of architect Harwell Hamilton Harris, then dean of UT’s School of Architecture. He became familiar with Harris’ work in California, while serving in the military. With an aversion to cold weather, he and his new wife Loretta (Lori) headed to Austin and like many UT students decided to settle in the city after graduation. Nill worked for several firms throughout his career, including Jessen, Jessen, Millhouse and Greeven. When the economy faltered in Austin in the 1980s, Nill focused on designing churches in Austin and Central Texas. Projects included St. Theresa’s Catholic Church, additions to St. Louis King of France Catholic Church and parishes in Bremond, Rockdale and Granger.8 According to Mrs. Nill, he retired from the Texas Department of Health and Human Services.

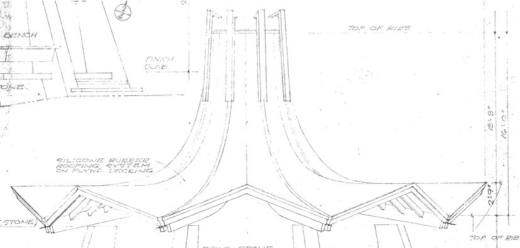

Lori worked in the offices of several architecture firms in Austin as a secretary and bookkeeper and she became involved with NAWIC as a founding member of the Austin chapter.9 She also worked for John as his private practice grew. In 1965, while serving as the chapter’s President, Lori and the group conceived the idea of the gazebo for Town Lake. At her urging, John agreed to personally design the gazebo on behalf of NAWIC.10 Per Mrs. Nill, John referred to his final design for the gazebo as an “inverted morning glory.”11 He designed the gazebo to compliment nearby Municipal Auditorium (demolished 2002). With his design, the group was ready to launch the project as a gift to the City of Austin.

The United States was awash with optimism, opportunity and automobiles post-World War II. As more and more households boasted at least one vehicle in the driveway and roads were improving across the country, family driving vacations became the preferred mode of transportation and the opportunity to see sights from coast to coast took center stage. Restaurants, hotels and gas stations looked for a way to stand out among the plethora of options. As California became a destination state, a unique architecture emerged and set the trend for two decades of design.

Inspired by the futuristic, space-age architecture born in Southern California, Googie architecture was first conceived by John Lautner in 1949. The concept swept the landscape of this modern era and even appeared at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York and in Tomorrowland at Disneyland. “Googie made the future accessible to everyone,” says Alan Hess, architect and historian.12

The architectural style emulated by the gazebo was originally categorized as Modern and more specifically by some as Coffee Shop and by others as Transportation style architecture. But Architecture critic Douglas Haskell was the first to coin the phrase “Googie”, meant to be a pejorative term to minimize and belittle the style.

While California boasted the style’s beginnings, Googie architecture was a national phenomenon and made its way to Texas. Googie is characterized by boomerang and amoeba shapes; atomic shapes based on the atomic model; buildings resembling spacecraft and exposed steel beams, to name a few.13 Googie was at its peak in 1965 when NAWIC introduced its concept of a gazebo to the City of Austin. The gazebo’s hyperbolic paraboloid roof also contains elements known as shell construction. Shell construction’s concrete walls and roofs have few structural columns and can span significantly in relation to the structural support. However, Googie is not a term recognized by Mrs. Nill and the roof of the gazebo was originally made of glue-laminated (glulam) materials.14

The design of the gazebo remains virtually unchanged since its original construction. But, in 1984, after 15 years of use, the structure needed major repair. NAWIC leadership came forward and put a plan in place to raise the money necessary for the repairs. Fundraising efforts included annual “Gazebo Runs” and selling black-and-white posters of the gazebo by artist Lynne Hough. At that time, the gazebo was renamed the Fannie Davis Town Lake Gazebo by City Council resolution.15 Mrs. Davis was a founding member of the Austin chapter of NAWIC. No structure in Austin had been named after a living honoree before that time.16

Over the years, the Chapter was called upon to protect the gazebo and ensure its proper maintenance. More repairs were needed in the 1990s and NAWIC members established the first in a series of Gazebo Fun Runs. Under the watchful eye of NAWIC members and those involved in the project from the outset, workmanship over the years continues to meet or exceed the high standards set by the original builders. In 1992, the small opening at the tip of the roof was covered by an acrylic bubble, allowing light to filter through the opening, while preventing water and rain from flowing into the opening of the roof. The bubble is attached to a light reflecting ring. In 1995, NAWIC members funded the handicap-accessible ramp in celebration of the gazebo’s 25th anniversary.

In 2010, the city considered a project to fill in the reflecting pond and repurpose the gazebo. NAWIC again intervened and, with the support of the community, convinced the council to spend money for improvements to the gazebo and its surroundings.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission awarded a $2 million grant to the Austin Parks and Recreation Department in 2011 to make improvements to Auditorium Shores. A portion of the funds included a renovation of the pond next to the Fannie Davis Gazebo into an environmental element used to treat parking lot runoff.

Most recently, in 2012, the city of Austin spent $137,000 to improve the pond, fix some structural elements, update some electrical wiring and repaint the gazebo to match its original color palette.17 The work was completed in 2012, under the supervision of John McKennis of Austin’s Parks and Recreation Department.18

The scope of work included a report by engineering consultants of the existing wooden frame and roof membrane, installation of a new roof, painting of the structure to match original color scheme and anti-graffiti coating on the concrete benches. Additional site work related to the surrounding landscaping and pond will be coordinated with the Watershed Protection Department through future phases of work along Auditorium Shores.19

The Fannie Davis Town Lake Gazebo is a statement structure that contributes to the character, beauty and active lifestyle that defines Austin.

This article was originally published in Docomomo US/MidTexMod's January 2017 newsletter.

Lori Martin is a Preservation Austin board member. In 2016, she took an unconventional detour and returned to the University of Texas at Austin to pursue a Master's in Historic Preservation. Much of her career has been in fundraising and development for nonprofits, specifically for organizations with a preservation focus. Most recently, Martin was the Director of Development for the historic Paramount and Stateside Theatres in Austin.

Notes

1. Handbook of Texas Online, Neil Sapper, "Johnson, Claudia Alta Taylor [Lady Bird]," accessed November 27, 2016, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fjocd.

Uploaded on June 15, 2010. Modified on June 9, 2016. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

2. Glen Castlebury. “Gazebo Approved for Town Lake.” The Austin Statesman pg. 6. Wednesday, November 10, 1965.

3. Handbook of Texas Online, "Lady Bird Lake," accessed November 27, 2016, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/rollb.

Uploaded on June 15, 2010. Modified on January 31, 2012. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

4. “Constructions Gets Underway on New Town Lake Gazebo.” Citizen Guide. Wednesday, July 3, 1968

5. “Comment.” The Austin Statesman pg. 4. June 4, 1969

6. “Gazebo Dedication Set Today.” The Austin Statesman (1921-1973), June 8, 1970. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Austin American Statesman pg. 15

7. Anne-Marie Evans. Staff Writer. “Gazebo – It’ll Open on Town Lake in Spring,” Austin American-Statesman, October 19, 1969

8. Lori Nill (former President, Austin Chapter, National Association of Women in Construction) in discussion with the author, November 2016.

9. Lori Nill.

10. Christine Adame. Stories from the Fannie Davis Gazebo

11. Lori Nill.

12. Matt Novak. “Googie: Architecture of the Space Age.” Smithsonian.com. June 15, 2012

13. Retro Staff. “Googie Architecture.” Planet Retro, RetroPlanet.com. April 28, 2010

14. Nill, Lori (former President, Austin Chapter, National Association of Women in Construction) in discussion with the author, November 2016.

15. June 4, 1984, Council Meeting

16. “History of the Fannie Davis Town Lake Gazebo.” www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Parks/Planning_and_Development/History_of_the_Fannie_Davis_Town_Lake_Gazebo%20pdf.pdf

17. Michael Barnes, “Gazebo by Lake Back in Pristine Condition,” Austin American-Statesman, November 3, 2012

18. Kim McKnight, email message to author, October 20, 2016

19. Kim McKnight, email message to author, November 8, 2016