Elizabeth Munyan, the recipient of Docomomo US Northern California (NOCA) Chapter’s 2019 Travel Grant for Students & Emerging Professionals, writes about her experience attending the 2019 National Symposium in Honolulu.

The central theme of the National Symposium was how Hawaii’s unique context allowed for blurring the boundaries between contrasting elements. This was most apparent in the built environment through the blending of indoor and outdoor spaces and the merging of East and West.

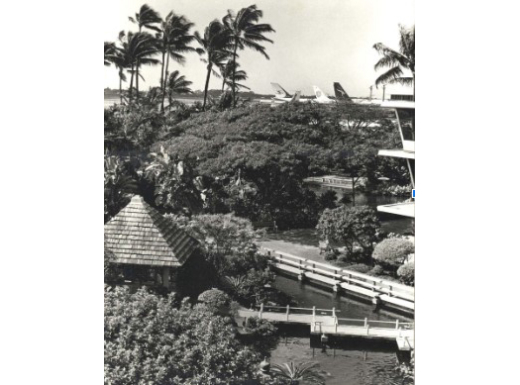

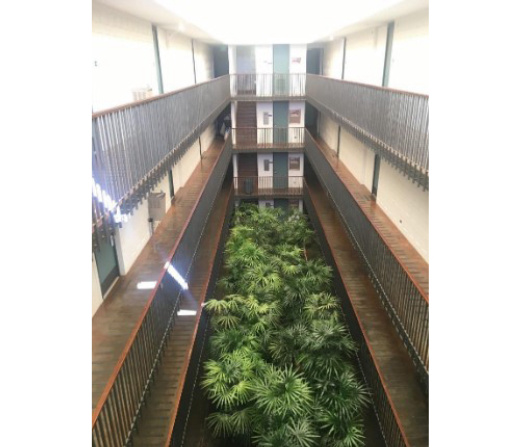

From the moment I landed at the Honolulu International Airport, I was greeted with the embodiment of indoor-outdoor spaces through Vladamir Ossipoff’s concept of “Environmental Living.” Environmental Living is a term coined by Ossipoff, in which buildings were constructed in ways that took advantage of cooling winds, dramatic views, utilization of natural materials, and the suppression of distinct indoor and outdoor spaces. Environmental Living design intended to maintain contact with the earth, air and sky. Ossipoff typically did this in his residential designs through the use of glass walls, open ventilation, integration of landscaping and topography and minimal division between spaces. Although not a residential space, Ossipoff designed Honolulu International Airport in a way that fully embraces this concept. The airport terminal itself is indoor-outdoor as one can wait to board a flight under low-canopied open entryways and sit in a lush tropical garden in the center of the terminal.