The International Business Machines Corporation, widely known for its acronym “IBM”, and nicknamed the “Big Blue”, commissioned its facility in Boca Raton, Florida, to the office of Marcel Breuer and Associates. The project architects were Marcel Breuer and Robert Gatje (longtime partner at this firm). Breuer, a respected, well-known architect and mature designer, received this commission at the height of his career. He was a former student in the Weimer Bauhaus, and had been a close disciple of Walter Gropius, whose decisive and formative influence lasted throughout his long career, and became a defining friendship until his later years.

The IBM project responded to the need of a rapid and significant expansion of the company in Florida, which would include offices, laboratories and manufacturing facility. The complex would function for the research, development and construction of what was then, state of the art computer devices. The company moved to Florida to isolate itself from the corporate interests of New York. This was necessary in order to develop new ideas. The company had already established connections in the state, with NASA as one of their clients. Under the same roof, the company intended to streamline all phases inherent to what was then known as “data entry systems.” The System/ 360 model 20, which was then the first financially accessible computer for daily use of businesses. In the early 70’s IBM Boca Raton would develop what we know today as personal computers (PCs).

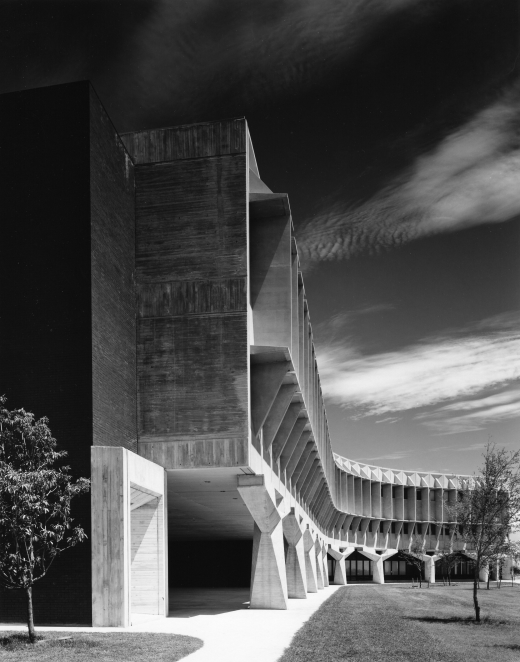

For Marcel Breuer and Associates, this would be the latest of several high-profile projects which would push them to the forefront of the architectural discussion. Although sometimes considered controversial works, their consistency and integrity would keep attracting attention to what they designed. Major institutional and corporate experiences dated back to the early 1950’s and into the 1960’s with projects such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development Headquarters (HUD), UNESCO Headquarters in Paris and an earlier work for IBM in La Gaude (France). Both projects had raised eyebrows with the heavy boldness of the use of concrete. Stepping each time a bit further into the application of the precast technique (which Breuer would oppose to the traditional poured concrete, naming the former as “old concrete”). Breuer understood his craft as a formal response to a combination of problems. An example is protection from the sun with brise-soleil. In his early projects, he used them as elements on the surface of the facade, while later he actually merges this function into structural parts of the building, as in this Boca Raton project. This is not only a technical feature, but also a time and cost effective one. His sensibility raises these solutions to a sculptural quality that would transcend the material while achieving an undeniable architectural unit. As Breuer himself stated, concrete was a universal building material, which could mold itself to his philosophical pursuits.[1] The office would receive more significant institutional and corporate projects, as it proved to have the ability to translate the intangible values these organizations were eager to express into form.