Primary classification

Secondary classification

Designations

National Register of Historic Places: July 29, 2005. (Condominium One)

National Register of Historic Places: December 12, 2018. (Baker House at Binker Barns)

Author(s)

How to Visit

The Sea Ranch Lodge is open to the public. Houses and recocreation facilities are open to residents and guests.

Location

Shoreline Highway (California State Route 1)95497, 95480

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Designer(s)

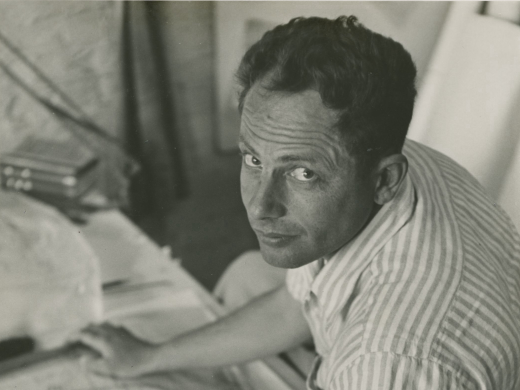

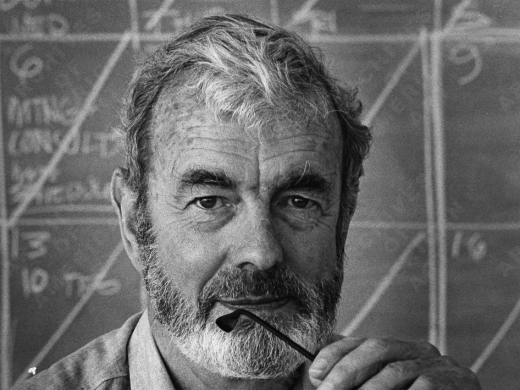

Charles Moore

Architect

Nationality

American

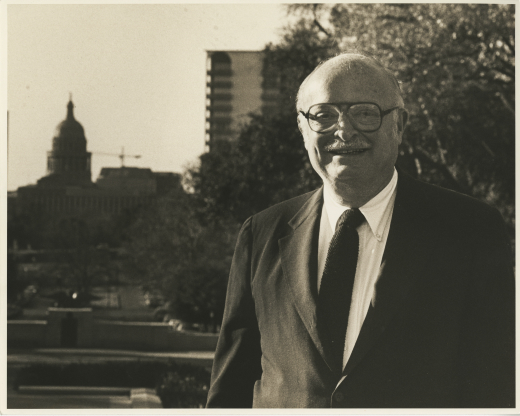

Lawrence Halprin

Nationality

American

Moore Lyndon Turnbull Whitaker

Joseph Esherick

Other designers

Masterplan Landscape Architect: Lawrence Halprin.

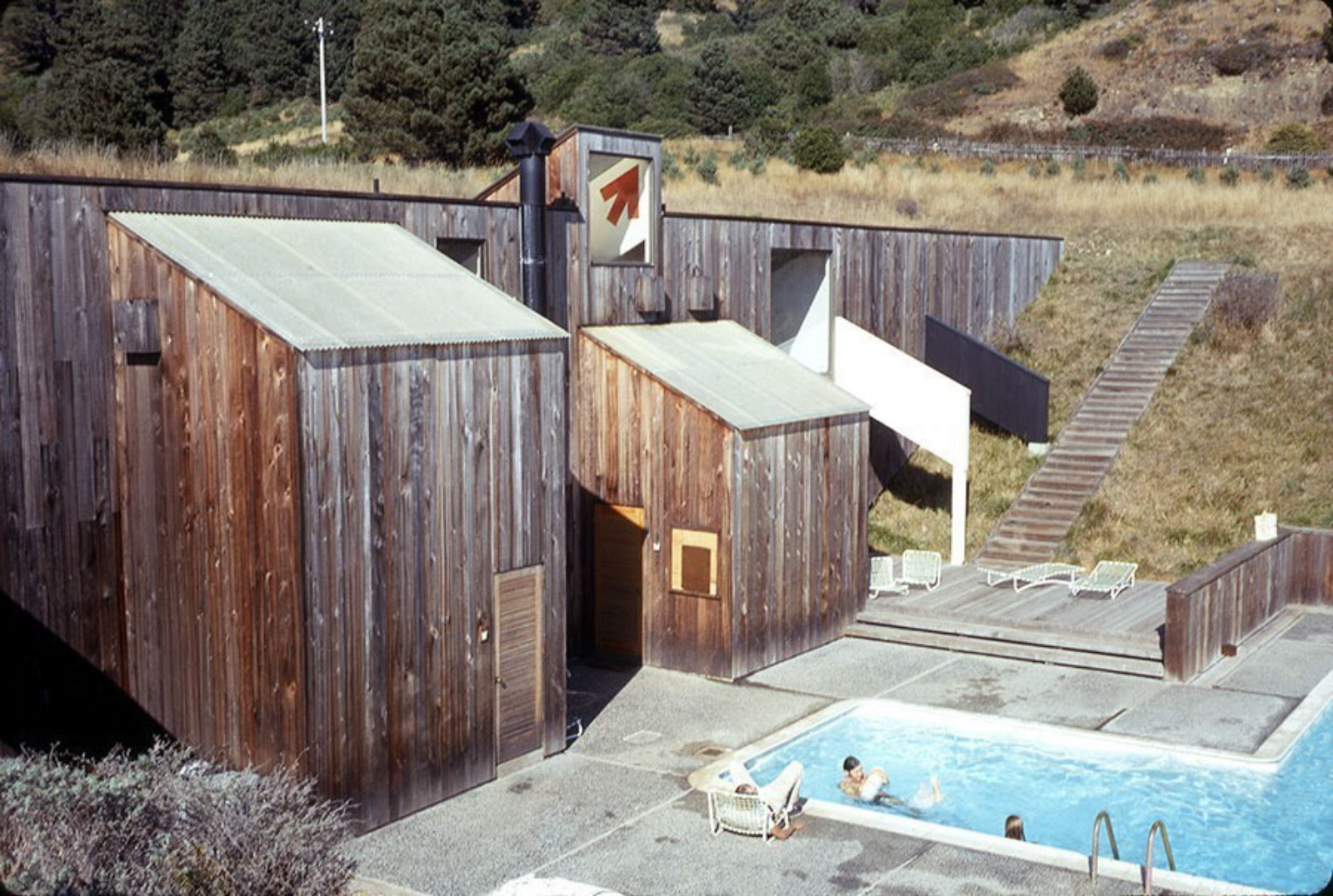

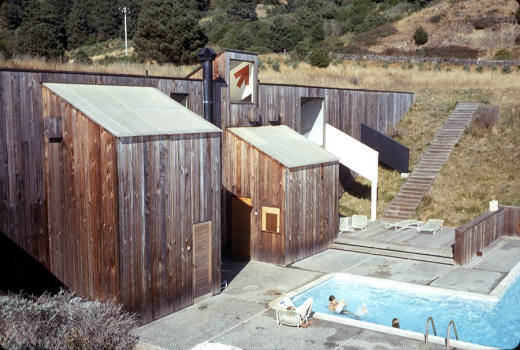

Architects, 1965 Condominium One, 1966 Moonraker Athletic Center: Charles Moore, Donlyn Lyndon, William Turnbull, Richard Whitaker (MLTW); Condominium One Structural Engineer: Patrick Morreau; Moonraker Interior and Graphic Design: Barbara Stauffacher Solomon. Moonraker Landscape Architect: Lawrence Halprin; Builder: Matthew Sylvia.

Architects, 1966 Hedgerow Houses: Joseph Esherick & Associates; Builder: Matthew Sylvia.

Architects, 1968 Sea Ranch Lodge: Joseph Esherick, Louis Mclane, Agora Architects; Design Consultant: Alfred Boeke; Builder: Matthew Sylvia.

Additional Works of Significance

__________________________

Architects, 1965 Johnson House, 1968 Binker Barns, 1969 Caygill House, 1970 Rush House: MLTW/ Moore Turnbull; Builder: Matthew Sylvia.

Architects, 1971 Ohlson Recreation Center: MLTW/ Moore Turnbull with Donlyn Lyndon; Builder: Matthew Sylvia.

Architect, 1972 Walk in Cabins, 1985 Brunsell House, 1998 Clayton house: Obie Bowman.

Architect, 1972 Kirkwood House: Paul Hamilton.

Architects, 1973 Madrone Meadow Cluster Houses: MLTW/ William Turnbull; Builder: Matthew Sylvia.

Architect, 1984 Halley House: John Halley; Builder: John Halley.

Architect, 1985 Ewry House, 1985 Wilde House: Donald Jacobs.

Architects, 1985 Employee Housing, 1989 Anderson House: William Turnbull Associates; Builder: Matthew Sylvia.

Architects, 1985 Maslach House, 1997 Schneider House: Esherick, Homsey, Dodge, and Davis.

Architect, 1985 Sea Ranch Chapel: James Hubbel.

Architect, 1987 Michaels House: W. Scott Ellsworth.

Architects, 1989 McKenzie House, 1991 Seagate Row, 1994 Lichter-Marck House: Lyndon/Buchanan Associates.

Architect, 1995 Del Mar Center: Ted Smith.

Architect, 1995 The Cottages: Fiona O'Neill.

Architect, 1996 Somers House: Robert Hartstock.

Architects, 1998 Yudell-Beebe House, 1998 Baas-Walrod House: Moore, Ruble, Yudell

Architects, 2001 Halprin House: Moore, Ruble, Yudell with Lawrence Halprin

Architects, 2002 Boyd House: Turnbull, Griffin, Haesloop