Awards

Design

Citation of Technical Achievement

Civic

Primary classification

Secondary classification

Designations

National Register of Historic Places (National Mall): October 15, 1966

Author(s)

How to Visit

Location

150 4th Street NorthwestWashington, DC, 20001

Country

US

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Other designers

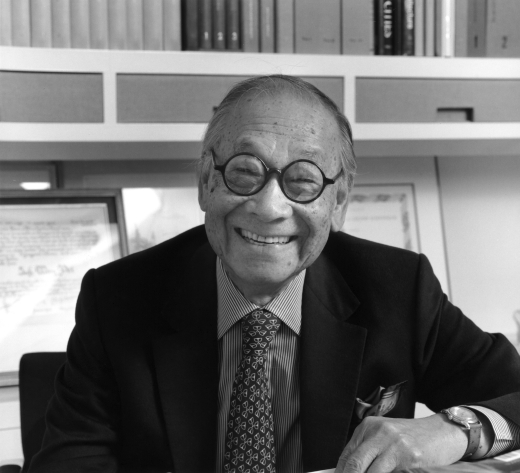

Architects: I.M. Pei & Partners; Partner in Charge: I.M. Pei; Project Architect: Leonard Jacobsen; General Designers: F. Thomas Schmitt, Yann Weymouth, William Pederson; Structural Engineers: Weiskopf and Pickworth; Landscape Architects: Kiley, Tyndall, Walker; Builder: Chas S. Tomkins Co.