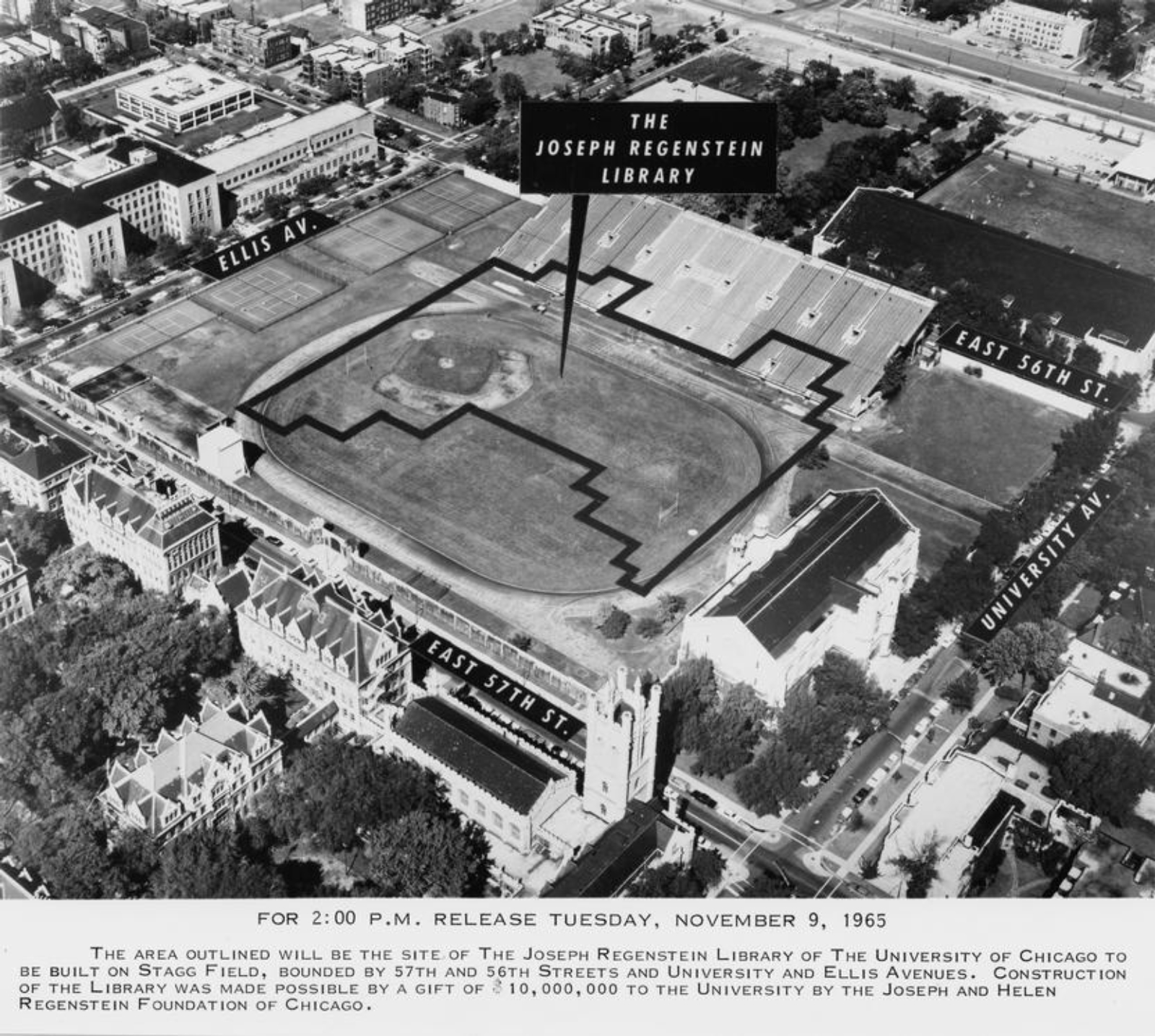

Site overview

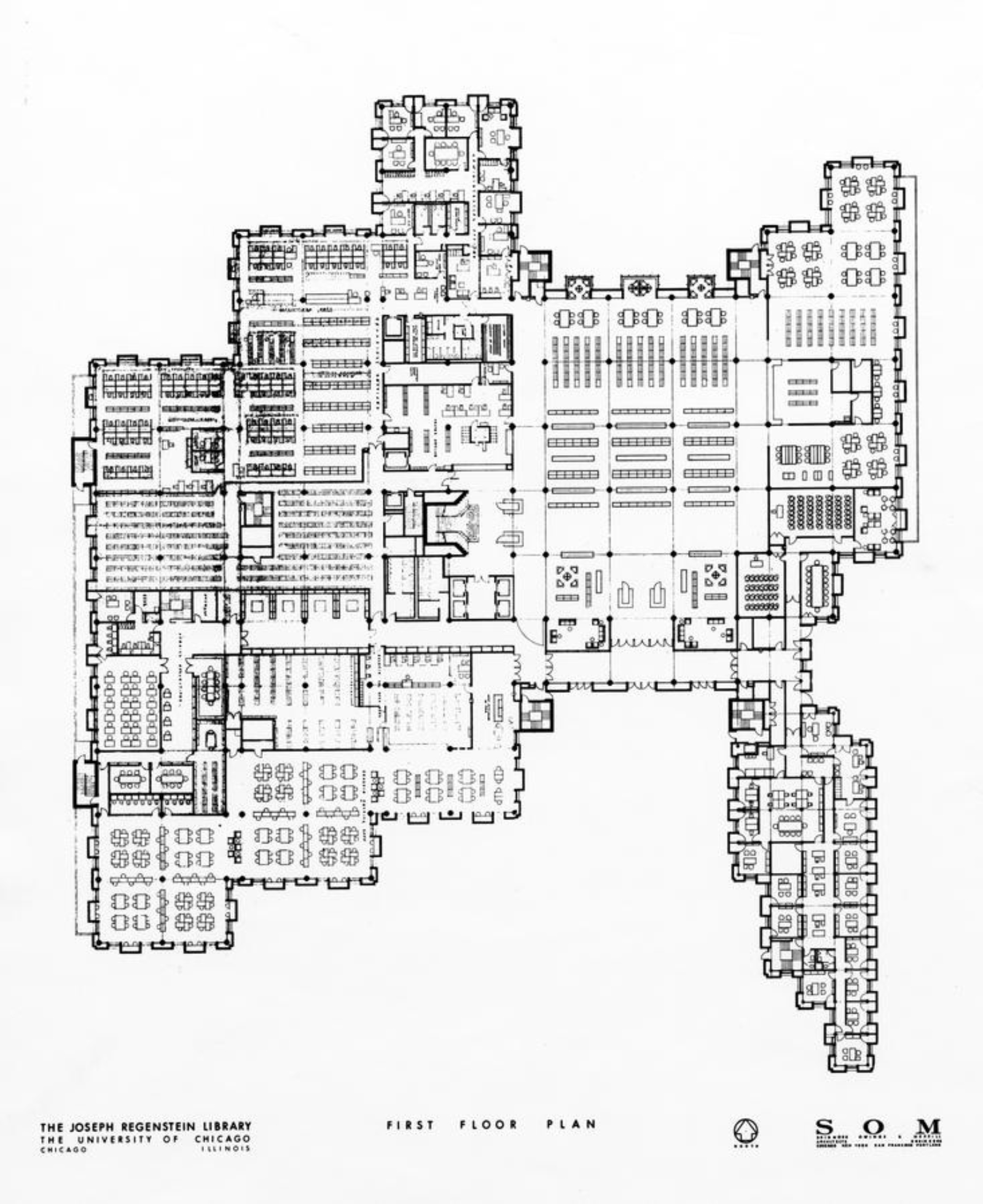

Regenstein Library has served as a key part of student life at the University of Chicago since its opening in 1970, and boasting 577,085 square feet, it is the largest library on campus. The reinforced concrete building features seven stories and a mechanical penthouse. It utilizes compact shelving on its B-level to maximize its storage capacities and house its diverse collections. Though the Regenstein Library is a work of Brutalist architecture, it honors the Gothic tradition by using positive and negative space in its mass to play with light and shadow. (Adapted from the website of the University of Chicago)