Primary classification

Terms of protection

Author(s)

How to Visit

Location

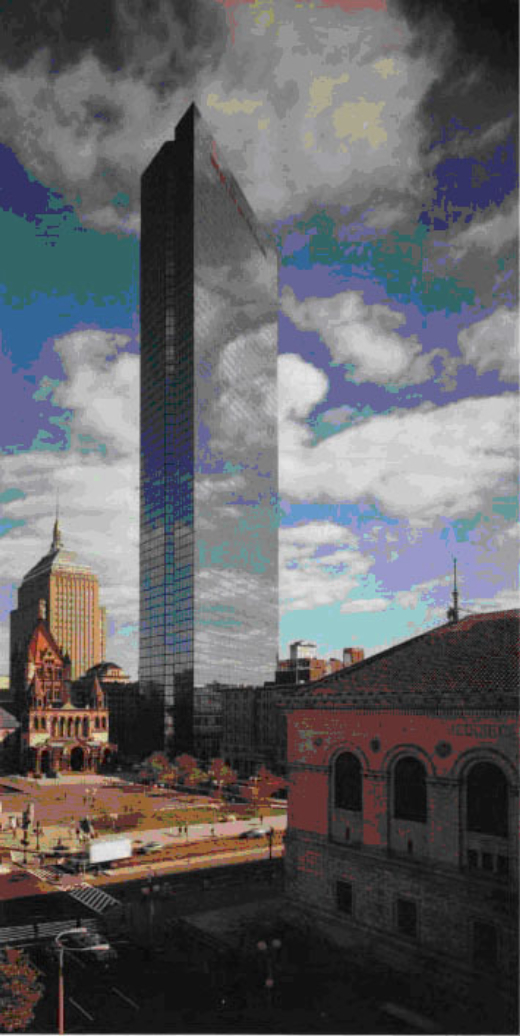

200 Clarendon StreetBoston, MA, 02116

Country

US

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Other designers

Architect(s): I.M. Pei and Henry Cobb

Other designer(s): Office of James Ruderman, NY, NY (Structural), Cosentini Associates LLP, NY, NY (Mechanical/Electrical), Mueser, Rutledge, Wentworth &. Johnson, NY, NY (Foundations)

Consulting engineer(s): Max Philippson , Professor Robert Hansen, MIT , Bruno Thurlimann, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology , A. G. Davenport, Director of the Boundary Layer Wind Tunnel, University of Western Ontario

Building contractor(s): Gilbane Building Co., Providence, RI (General Contractor), H.H. Robertson Co. (curtain wall subcontractor)