How to Visit

Open by appointment for official U.S. citizen services

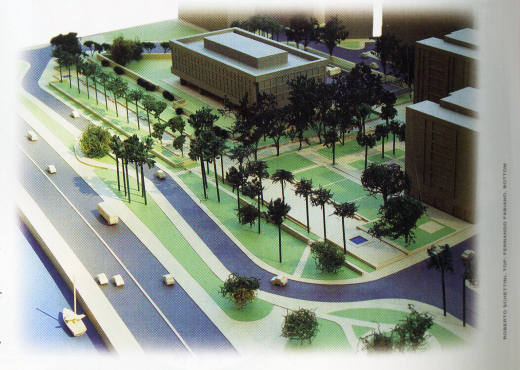

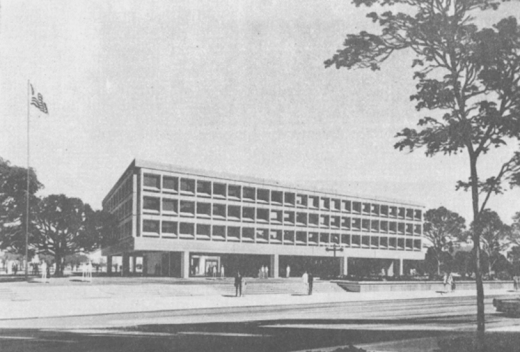

Location

Lauro Muller 1776Montevideo, , 11200

Country

uy

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Other designers

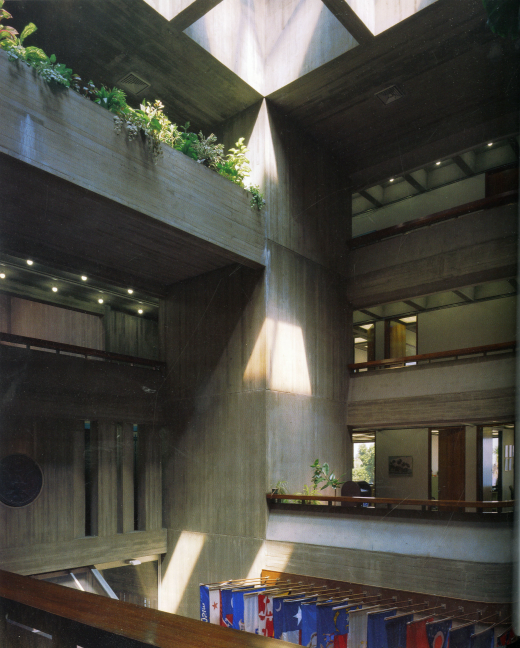

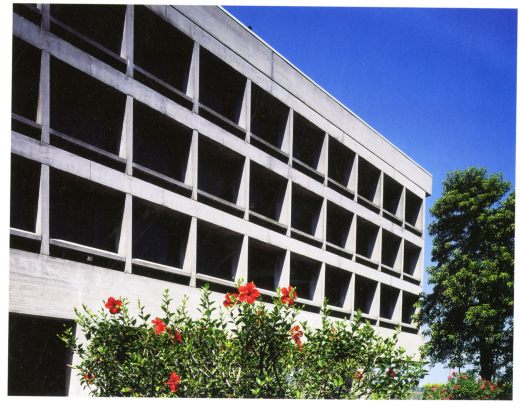

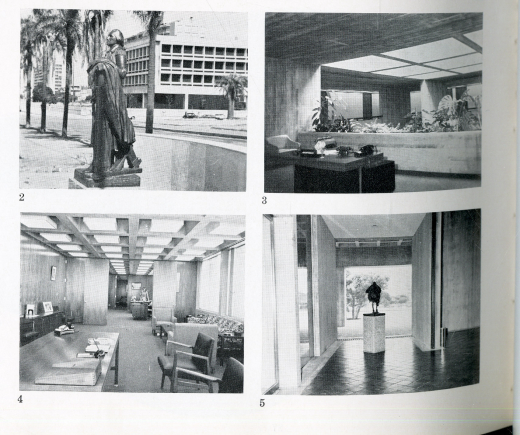

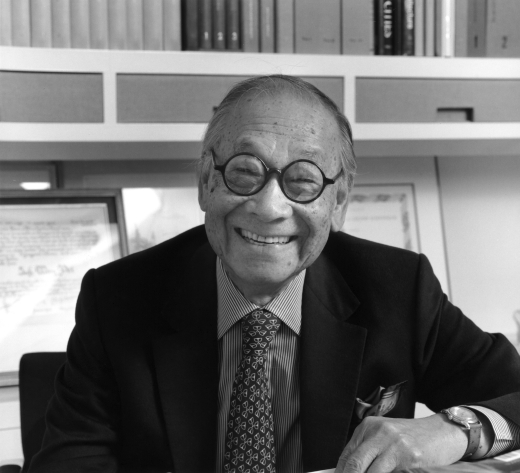

Design Principle: I. M. Pei. Project Architect: Pershing Wong; Associate Architect: John LoPinto and Assoc.; Juan B. Maglia, President of the Comisión Financiera de la Rambla Sur; Construction Firm: Empresa Carcavallo S.A., Washington Carcavallo, Vice President; Consulting Engineer: Horacio García Capurro