Production of the built environment is elongated, contentious, and polyphonic. Architecture as a cultural phenomenon is correspondingly incremental, overlapping, and diffuse. Reading its trajectory in the moment is not easy.

That’s my excuse for thinking 1993 was entirely forgettable at the time. I’m able to recall it as a discrete period only because it was my last full year in graduate school. At the time. Postmodernism seemed like a fact of life, and my classmates and I grimly expected to end up in offices drafting pink pediments for the foreseeable future. That is, if we found jobs: the sense of stasis was underlined by the fact that very little built work was being completed, following on from a mild recession in 1990. But, while it felt like nothing was happening, 1993 was arguably the stealth vertex of a parabolic arc from the concerns of Postmodernism to those of our present period.

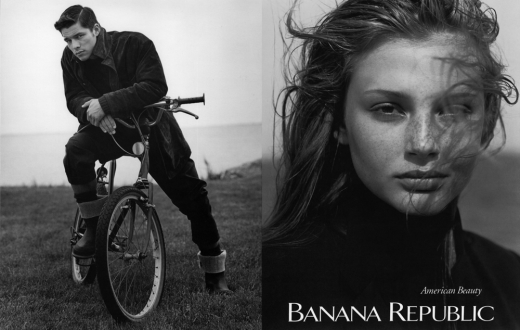

As it turned out, 1993’s forgettability was less a bug than a feature — the result of a widespread muting of expression in mainstream material culture. After generations of vivid, sometimes raucous experimentation with cultural aesthetics in the US, the 1990s saw efforts to establish a baseline of straightforward good taste.[1] Casual and undemonstrative, this mutation of Yankee propriety was derived from high-end sources (e.g. Calvin Klein and Scandinavian Modernism) and broadcast by mass retailers like Banana Republic and Crate&Barrel. The mother avatar of the sensibility was Martha Stewart, whose first television show aired in weekly syndication from September 1993. Crucially, this new version of good taste was broadly accessible, not rarified: the oncoming national wave of Starbucks provided the model for a suitable ambience that cut across class lines. The cultural results proved extremely durable; for better or worse, the pilot episode of Friends (1994) feels bemusingly close to our current world. (For comparison, the equivalent in 1993 would be watching vintage-1968 Gomer Pyle USMC) In many ways, we’re still living with 1993 now.