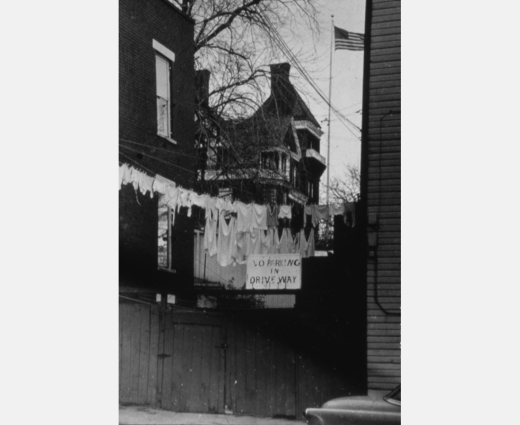

During the 1950s and 1960s, architectural models, maps, and renderings helped local boosters justify and build support for urban renewal in communities across the nation. New York City’s master planner Robert Moses helped pioneer this practice. Urban historian Themis Chronopoulos has analyzed how brochures produced by Moses’ Committee on Slum Clearance juxtaposed images of actual (if outdated) places – tenements, corner stores, back alleys – against illustrations depicting the sleek, modern residential and commercial structures that might be built in their stead.

Selling Urban Renewal: A Model Approach

Author

David Hochfelder, University at Albany, SUNY; Ann Pfau, independent scholar; Stacy Sewell, St. Thomas Aquinas College

Tags

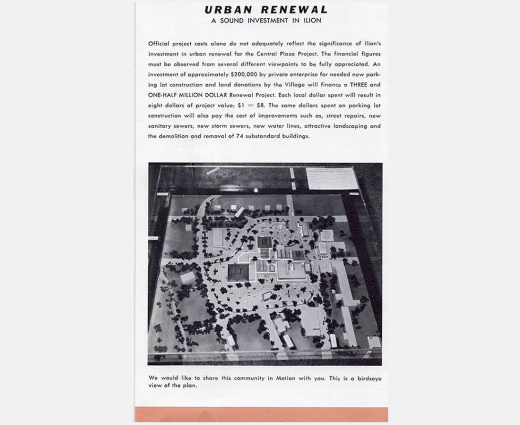

By the 1960s, this practice had spread across the nation to become a key element of most planning-stage publicity campaigns. At that point in the process, most residents were mildly supportive, believing redevelopment would benefit their cities. They had yet to see firsthand how urban renewal would destroy neighborhoods, shaking up the lives of local residents and business owners. Once the bulldozers started up, this mild support typically evaporated, replaced by widespread skepticism, even active opposition, especially among those who would be displaced.

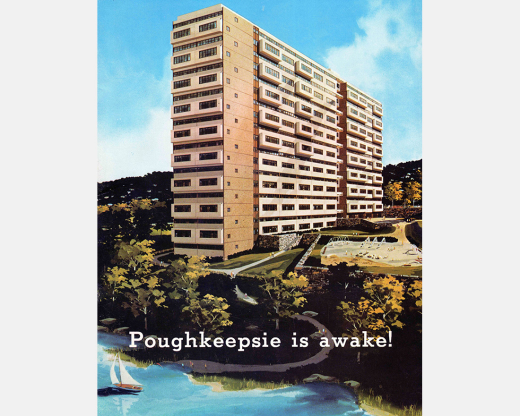

Urban renewal’s promise was that demolition and reconstruction of downtown neighborhoods and retail districts would bring wealthier, whiter residents and consumers back to the city, thereby rebuilding tax bases diminished by post-World War II suburbanization. The problem was that federal grants, which funded most of the planning and site clearance, did not extend to market-rate residential and commercial construction. That component of urban renewal depended on the city’s ability to attract private developers willing to build what city leaders planned. In many places, what was eventually built – often many years after the end of demolition – was significantly different from what had been planned and initially advertised.

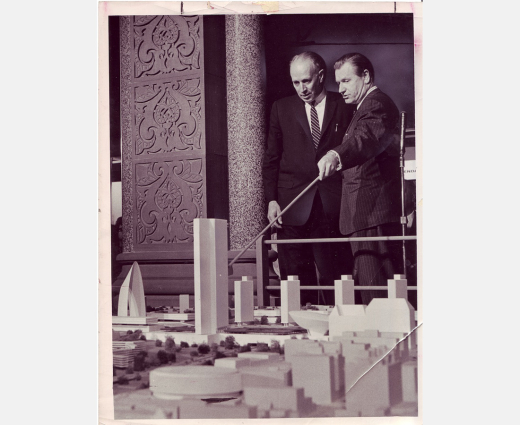

Most three-dimensional models bore little relation to what would eventually be built, because their purpose was to impress, not to render a faithful depiction of a project’s outcome. In the words of one Kingston, NY, city council member, such models gave the public a “view of something that could take effect.” By contrast, he complained, “You can’t get anything across with a map, or advertisements in the paper.” During the period before demolition commenced, the model showing what downtown Kingston might look like after redevelopment was displayed at locations across the city, including at a booth at the annual Lions Club show. It also served as a prop at a public hearing on the city’s urban renewal plan. The model appears to have had the intended effect. At the unveiling, a reporter for the local newspaper claimed to have overheard remarks like, “It’s too good to be true,” and “Won’t we be proud of downtown when the project is completed?”

In Albany, Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller decided to build a Modernist state office complex adjacent to the State Capitol in the middle of a 19th-century residential and commercial neighborhood. Unlike federally funded urban renewal projects, the State of New York did not have to entice private developers to build on the 98-acre site after it was cleared. Rockefeller used models to justify the expenditure of what would be roughly $2 billion (including financing costs) by its completion in 1978. When the State seized the area in March 1962, nobody knew what would take the place of the roughly 1,200 buildings, 400 small businesses, and 7,000 residents. The following year, the governor unveiled two models. The first reflected his plan to build a capital complex complete with arterial highway (today known as the Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza and South Mall Arterial). The second illustrated his vision for a renewed downtown Albany, something that would have required additional land takings. The first model looks much like what was built. The second does not, mainly because Albany’s Democratic machine declined to cooperate.

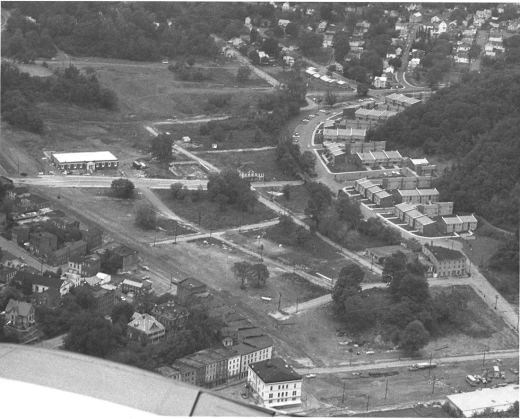

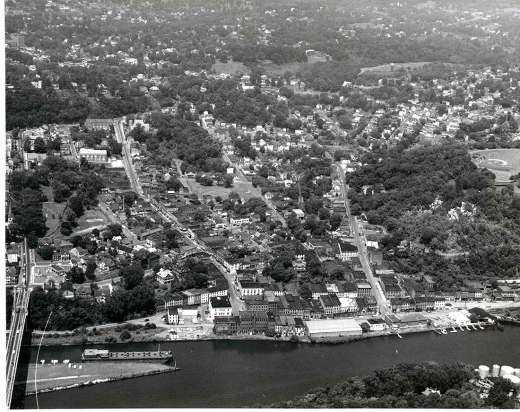

Even after urban renewal demolitions were underway, renewal officials continued to exhibit “present day” photographs – the more obviously blighted the better – alongside models and renderings of what might be. In 1966, as Kingston’s downtown renewal program was coming under increasing criticism, city leaders once again exhibited the model alongside photographs of demolished structures at the Lion’s Club. In Albany, state officials developed a slideshow of photographs and renderings to create a spectacular comparison between the old and new. State officials used this slideshow and script at several public meetings around Albany. Later, at the ceremony to commemorate the end of demolition and beginning of construction, Gov. Rockefeller sealed an album of “before” photographs inside the South Mall cornerstone. The models and renderings were on exhibit in a tent near the dais.

This same comparison between present-day blight and a modern, if generic, future animated the brochures that municipalities across the nation created to promote their urban renewal programs. Local officials distributed these brochures at public meetings and to members of the press.

The extent to which these promotional efforts succeeded in selling local residents on urban renewal projects is unclear. Glossy images and dramatic models likely appealed most to those who were least affected by the upheavals caused by these projects. However, we have yet to identify an urban renewal project that proceeded without protest – first by displaced residents and business owners, later by taxpayers and preservationists. In the long run, these later protests proved more effective, at least in part because they reflected the priorities of wealthier and whiter residents.

In the 1950s and 1960s, proponents of urban renewal pointed to blighted buildings and old-fashioned architecture to make the case for wholesale demolition. By the mid-1970s, however, city leaders and planners came to regard these same buildings – without the poor people living inside them – as drivers of economic development. Gentrification was the logical outcome of both urban renewal and the historic preservation movement that was its backlash.

David Hochfelder is associate professor of history at University at Albany, SUNY.

Ann Pfau is an independent scholar.

Stacy Sewell is professor of history at St. Thomas Aquinas College.

The three are developing Picturing Urban Renewal, a digital history of urban renewal in New York State. The project is presently at the prototype stage and is pending on production funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.