By Theodore Prudon

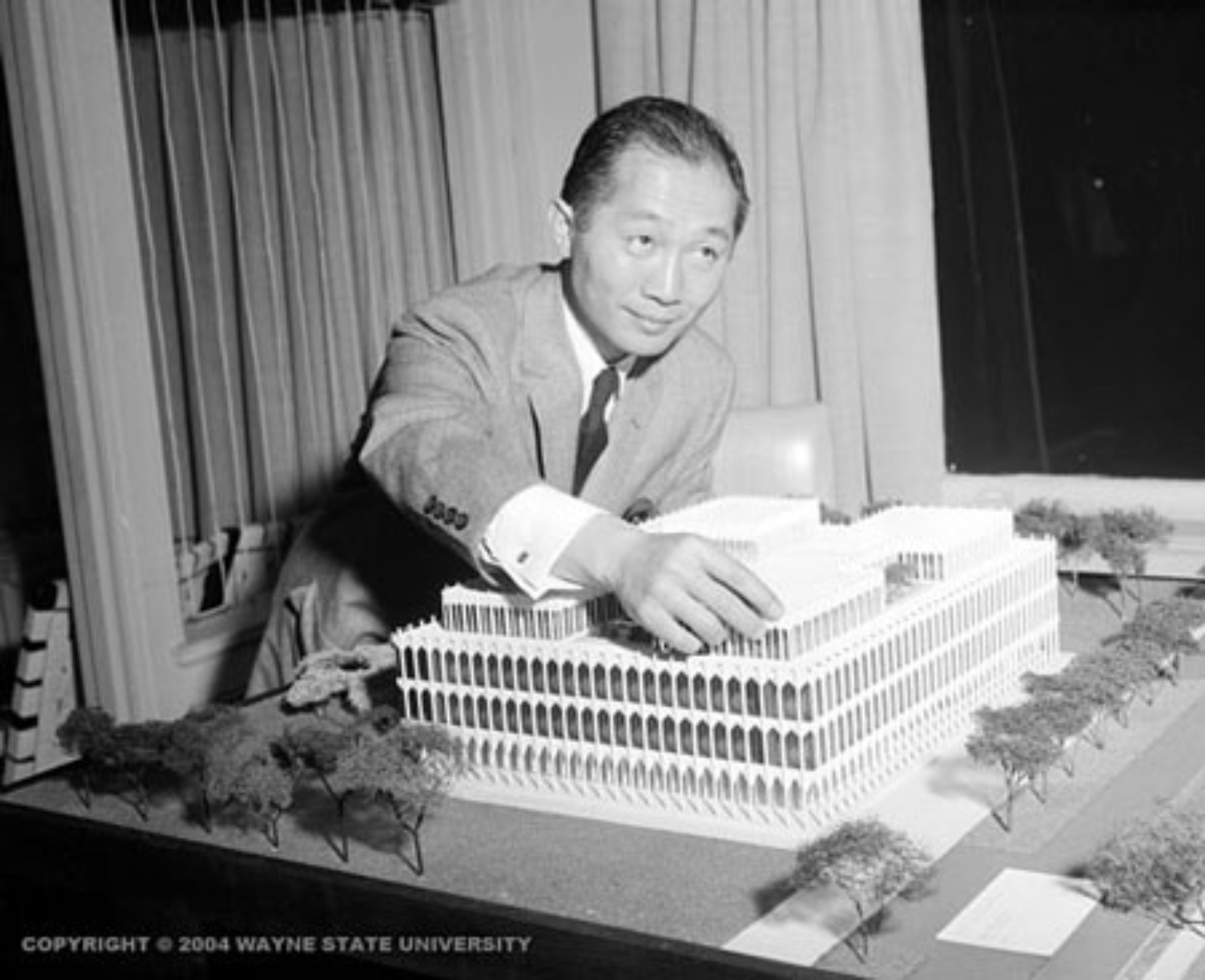

When Minoru Yamasaki was selected for the design of the twin towers of the World Trade Center, the New York Times noted: “Mr. Yamasaki is considered one of the country’s foremost architects”. As if to confirm that statement, four months later on January 18, 1963, he was on the front cover of Time Magazine surrounded by parts of his buildings following in the footsteps of Frank Lloyd Wright, Eero Saarinen and Edward Durell Stone.

When Minoru Yamasaki was selected for the design of the twin towers of the World Trade Center, the New York Times noted: “Mr. Yamasaki is considered one of the country’s foremost architects”. As if to confirm that statement, four months later on January 18, 1963, he was on the front cover of Time Magazine surrounded by parts of his buildings following in the footsteps of Frank Lloyd Wright, Eero Saarinen and Edward Durell Stone.

Yet some fifty years later, his work, once widely known and not always praised, has not been the subject of a great deal of study, something he shares with his contemporary, Edward Durell Stone. This comparison is not entirely accidental but rather a reflection on how their work was perceived at the time. Both men in reaction to the orthodoxy of strict modernism sought to reintroduce more detail and, as some would argue, more ornament into architectural design, attempts that often resulted in negative reviews from leading architectural critics. While the planning of their buildings remained in many ways functional and true to modernist principles, their elevational treatments moved away from modernist orthodoxy to the dismay and, sometimes, the ridicule of architectural peers. This presents us, who now must decide what to preserve and how, with the question as to how to value those opinions in the rearview mirror of history.

After completing the U.S. Science Pavilion in Seattle and having been awarded the commission for the World Trade Center, the Time Magazine profile contained a series of comments on Yamasaki’s work from such colleagues and academics. In reviewing his design of the McGregor Memorial Community Conference Center at Wayne State, now easily appreciated as an elegant gem and in good condition on the university campus, Vincent Scully called it a “twittering aviary”, Philip Johnson commented that the building lacked strength and Gordon Bunshaft was perhaps the most severe: “Yamasaki’s as much an architect as I am Napoleon. He was an architect, but now he’s nothing but a decorator. Sure, people are getting bored with the glass box – I am too. But now there’s this clique that says, ‘Let’s build a building,’ and there is not even a thought to the architecture.” Others, including Walter Gropius and Wallace Harrison (who once employed Yamasaki in his New York days), however, are more positive. In the words of Pietro Belluschi, then the dean of architecture at MIT: “I do not necessarily adhere to all that Yama preaches, but he is not to be devalued at all. We cannot dismiss even his Seattle Fair. It has gaiety and a soaring that appeals to the public.”

These opinions on the work of Yamasaki have to be placed in a larger context against the backdrop of the debate taking place in the 1960s between those that adhered more strictly to classic modernist and those that have been called the New Formalists and our own hindsight following Postmodernism. These earlier criticisms, until very recently, have affected perceptions and reputations immensely as illustrated by the relative lack of study and information. Moreover, many of these earlier opinions are brought back to life again as arguments against preservation today. This necessitates a process of re-evaluation that only has just begun and some of these earlier observations with the benefit of the distance of time seem less valid, and these architectural and esthetic solutions appear actually intriguing.

To return to Yamasaki and his work, his designs for the McGregor building at Wayne State and the Reynolds Metals Regional Sales Office, Southfield, Michigan, were award winning and demonstrate the best of Yamasaki’s ability to embrace modern architectural vocabulary yet provide detail, quality of material and interesting spatial qualities. For the exterior of the Reynolds Metals building, he demonstrates – intentionally – the potential of aluminum in two distinctly different ways, one, as a more traditional curtain wall and two, as a brise soleil and decorative screen. The screen is mounted in front of the curtain wall some distance away so the space in between can be used for galleries providing access for the window washers. Even these galleries, with their perforated floors, add to the overall sense of screening. The exterior screen made of a gold colored anodized aluminum is divided by vertical fins in sections, which in turn are filled with screens of small overlapping circles creating the “play of sun and shadow” which Yamasaki so admired in earlier architecture.

To return to Yamasaki and his work, his designs for the McGregor building at Wayne State and the Reynolds Metals Regional Sales Office, Southfield, Michigan, were award winning and demonstrate the best of Yamasaki’s ability to embrace modern architectural vocabulary yet provide detail, quality of material and interesting spatial qualities. For the exterior of the Reynolds Metals building, he demonstrates – intentionally – the potential of aluminum in two distinctly different ways, one, as a more traditional curtain wall and two, as a brise soleil and decorative screen. The screen is mounted in front of the curtain wall some distance away so the space in between can be used for galleries providing access for the window washers. Even these galleries, with their perforated floors, add to the overall sense of screening. The exterior screen made of a gold colored anodized aluminum is divided by vertical fins in sections, which in turn are filled with screens of small overlapping circles creating the “play of sun and shadow” which Yamasaki so admired in earlier architecture.It would seem that the time has come to look more closely at the architecture of Yamasaki and others like Edward Durell Stone practicing in the 1960s and 1970s and reassess the importance of their work and buildings. Hicks Stone’s (Eward Durell Stone’s son) recent book on the legacy of his father’s work is one positive step in this direction along with the preservation of the Yamasaki archive by the Michigan SHPO office. It is important to not only focus on their commercial architecture, which received most attention at the time. Their work is as representative of the period as the work of those who were their critics. After all it is history now and the choice is ours.