In the early spring of 1970 members of radical architecture and media art group Ant Farm, alongside fellow travellers SouthCoast, coordinated a seminar on “inflatables” - plastic, air-inflated buildings - on the Columbia, Maryland campus of Antioch College. Ant Farm, at this date, consisted of recent Yale architecture alum Doug Michels and Tulane architecture alum Chip Lord. SouthCoast members Tom Morey and Pepper Mouser documented the proceedings on the new recording medium of ½ inch format videotape.

Antioch Columbia was, at that point, a recent outpost of Antioch’s main campus in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Antioch College, founded by educational reformer Horace Mann in 1850, was most famous for being a hotbed of left political activism and the originator of the cooperative work-study education model. The traditional, leafy, Ohio campus consisted primarily of circa 1850s Greek and Gothic revival brick buildings.

The Antioch Columbia campus was initiated at the behest of visionary developer Jim Rouse, who designed Columbia, Maryland as a planned community intended to eradicate redlining, racism, and classism via careful civic engineering. Rouse felt that Antioch’s progressive stance and work/study model were a good match for his utopian planned city.

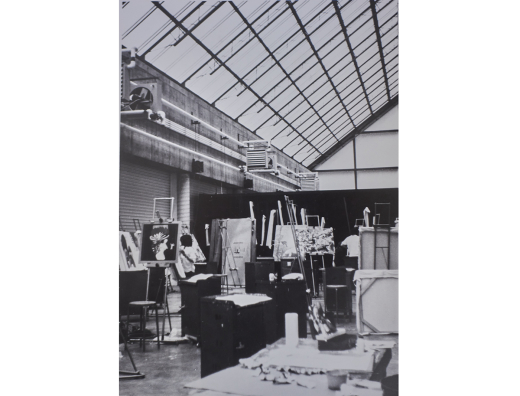

While at the 1970 inflatable seminar, Ant Farmer Doug Michels ran into Al Berney, Antioch’s VP of finance who was visiting the new Columbia campus. Berney was having some trouble with an architecture project on campus: the school had commissioned a new art building, and via a drawn-out process of design-by-committee, various members of the arts faculty had “exploded the scope” and forced the architect the college had hired, Richard Cook, to expand his design into a multi-building monstrosity which presented expenses far beyond Antioch’s budget.

Berney saw a cost-saving opportunity in the young designers (who had at this point never built a thing besides inflatables[1]) and explained his troubles to Michels, suggesting that they might create an inflatable art building on Antioch’s campus. Michels also saw an opportunity, and, in the words of Tom Morey, “gave him the once-over and sketched out a real solution on the back of a napkin. A brutally basic loft structure that could be ‘extruded out’ in design to match the funds available.”(P. Mouser, personal communication, June 29, 2021) [2]