Shopping centers built between the 1950s through the 1970s on the island of Oahu are unique examples of Modernist architecture in Hawaii. They comprise the majority of large-scale commercial buildings on Oahu and amongst the other islands, which experienced a different level of commercial impact from tourism during the post-war era.

The mid-century shopping center was a microcosm for all that Hawaii had to offer: a unique combination of local and Asian-inspired goods, as well as products brought from the US mainland. It was an advertisement unto itself, at both a pedestrian and automobile-friendly scale. Juxtaposed with the island’s natural geography, the simple architectural patterns, forms, and artwork were iconic throughout Hawaii’s neighborhoods.

Preserving Hawaii's Post War Commercial Development (2022 update)

Author

Alison Chiu

Affiliation

Docomomo US/Hawaii

Tags

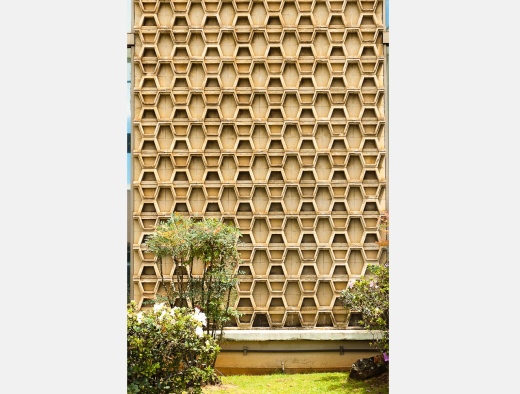

Various methods of modernist concrete forms adorned these structures, including precast arches, folded plates, thin shells, and barrel roofs. The Modernist architecture of post-war Hawaii blended an international east-west appeal and construction techniques, with a distinct regional style that looked to reinforce the unique quality of island life and articulate new perspectives on Hawaii’s multi-ethnic identity.

These shopping centers retain varying degrees of integrity. Over time, market-driven development and continuous renovations have erased a significant portion of the mid-century aesthetics. Occasionally, original elements such as sculptural artwork, breezeblocks, embedded signage or decorative manhole covers, and structural components hint at a comprehensively planned site design. At its construction in 1959, the Ala Moana Center was the world’s largest single application of pre-stressed concrete.

While appreciation for Modernism grows, conversely, many more resources are lost or altered. A decade ago, Sears Holding Corporation sold several of its retail stores to the Chicago-based company General Growth Properties, Inc., which immediately announced plans to close long-time tenant Sears department store at Ala Moana Shopping Center in Honolulu by the end of 2013. Sears was an anchor tenant of the shopping center for 54 years, since the mall’s construction by developer and contractor Hawaiian Dredging Company. Now a nostalgic memory, Sears disappeared as did many of the earliest shops (i.e., McInerny’s, Sato’s, Fishland, Crack Seed Center, etc.), in favor of new retail. Its original storefront and footprint ceased to exist with redevelopment of the mall’s Ewa (western) wing, which added over 340,000 square feet of new retail space in 2015.[1]

Along with the ebb and flow of retail tenancy since the mall’s inauguration, multiple additions and renovations have drastically altered the mall’s original appearance. Today, two main components retain their character from the original mall designed by architect John Graham & Company: La Ronde, the country’s first revolving restaurant, and Macy’s department store whose eaves showcase a Hawaiian-inspired tapa cloth design from its predecessor Liberty House, which was constructed during the 1966 eastern wing addition of the mall.

New chapters for these shopping centers are continually being written. The Ala Moana Shopping Center has undergone extensive renovations and numerous “face-lifts” to modernize its retail space. The mall, which originally housed up to 80 merchants on two levels, now offers four levels with more than 350 shops and restaurants under new owners Brookfield Property Partners.

Changes at the shopping center correlate to major periods of commercial development that occurred in Hawaii during the decades following World War II. With Hawaii’s admission to Statehood in 1959 and significant advances in commercial aviation, a large number of people flocked to the islands. Oahu, in particular, became a major hub for national and international travel for business and leisure. During the 1960s, the island experienced a significant economic boom, partially driven by tourism. This building boom directly spurred city planning and architectural development. It propelled the rapid transformation of what was once a sleepy island territory of plantation villages, sugar cane and pineapple fields, and mangrove forests into an international modern metropolis. Chain-stores and shopping centers, which had developed much earlier on the mainland during the 1920s & 1930s, now began to appear in Hawaii.

Modern shopping centers were often strategically located near highways. On Oahu, they still dot the built environment from the leeward to the windward side of the island. At the time, these commercial complexes presented a distinct new building typology to Hawaii’s vernacular. The new architecture wove together advanced structural engineering and eye-catching design to attract passersby in the newly-ubiquitous automobile, while also serving as a local nexus for the fast-growing residential communities that coalesced around them.

Hawaii’s commercial centers were generally one- to two-story high structures surrounded by ample parking. They offered a variety of connected shops, services, restaurants, medical offices, and department stores. Banks were often located near the parking perimeter as a separate structure, and featured repetitive geometric design details at metal screens or in cast stone. Gas stations designed on site or nearby exhibited simple, clean lines.

Supermarkets such as Foodland, Times, and Piggly Wiggly helped anchor each site, provided economic stability and encouraged further commercial and residential development in surrounding areas. In addition, state and government services such as libraries and post offices were often constructed within close proximity to these new commercial hubs. Clustered amenities such as these provided individuals and families with the mainland style of a “one-stop” shopping center.

Planning and developing just the right combination of complementary tenants was considered a specialized art form in the retail business. Small towns such as Aiea, Pearl City, Kailua, and Kaneohe, projected a high level of growth during the 1960s. Shopping centers were a driving social force that stimulated both residential and commercial development by providing a nucleus of goods, services, and community activity. By the end of the decade, approximately two dozen shopping centers alone contributed to more than half of the state’s retail trade.

Modern structures, with their expressionistic light-colored roof lines set against the evocative backdrop of Hawaii’s lush green mountains and blue skies, became iconic commercial elements within the cultural landscape. Many existing community shopping centers from the Modern era have since lost some of the characteristic grace and striking aesthetic they once had due to several combined factors.

Increased development density and construction of taller surrounding buildings contribute to a loss of feeling, setting, and association, while steady deterioration of materials and infrastructure slowly contribute to a loss of material integrity over time. Most significantly, malls suffer from a loss of design integrity through a multitude of alterations and renovations, which may appear ad-hoc and/or create a maze-like experience for visitors instead of representing the original cohesive planned vision.

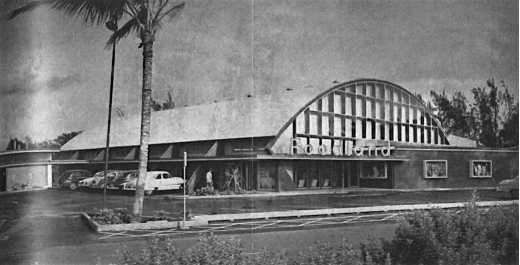

The Kailua Beach Shopping Center was designed by architects Wimberly and Cook and constructed in 1955. At its facade, load-bearing grilles with blue heat-absorbing glass have been replaced in favor of wood siding and a boxy, built-out overhang that provides shade for the multiple storefronts below. The overhang also conceals a portion of the precast concrete abutments flanking each side of the 90-foot clear span roof, which were exposed to showcase the elegant structural ingenuity of the original design and engineering. The original brick veneer liquor store which once stood adjacent to the supermarket entryway has since been demolished, and additional parking now stands in its place.

Planners, preservationists, residents, business owners, and visitors all experience Hawaii through different lenses. How do we reconcile these lenses and begin to articulate what level and quality of growth is “acceptable” within our island communities?

Commercial architecture inherently expresses a level of organic growth based on evolving community needs and practices. Which changes should be retained? Which community do these shopping centers serve, and how does the architectural typology reflect that individual community as it evolves?

The Hawaii 2050 Sustainability Plan envisions a more walkable Honolulu and aims to balance economic, social and community, and environmental priorities. “Our citizens inherently recognize that these three pillars of our society are interdependent. We want a vibrant, diversified economy; a healthy quality of life that is grounded in a multi-ethnic culture and Kanaka Maoli [Native Hawaiian] values; and healthy natural resources.”[2]

Locally, changing trends observed over the past decade include growing appreciation to support smaller businesses by local entrepreneurs; developing more assertive policies to help visitors practice responsible tourism; and cultivating broader awareness and respect for Native Hawaiian culture.

Hawaii has a long and complex history with tourism and cultural commercialization. Contemporary mid-century views on Native Hawaiian American identity, as seen through the lens of tourism, may now appear one-dimensional and potentially questionable. Adding to a preservationist’s dilemma, some mid-century design elements that were fashionably stylized to represent Hawaiian culture may be considered inauthentic or offensive today.

Resources of the recent past which showcased an international design aesthetic in regional architecture, represent an important period in Hawaii’s history and contribute to a larger conversation about community identity. Continued research and study of these shopping centers, the majority of which still primarily service neighborhood communities around the island, will help provide additional scholarly context regarding the development of Modern architecture and commercial infrastructure on the island. With the Hawaii 2050 Sustainability Plan and the need to address present and future economic realities, preservation of these mid-century structures is an imminent issue that will impact both cultural and material sustainability in the years to come for everyone in Hawaii.

Notes

- https://www.bizjournals.com/pacific/news/2015/03/02/general-growth-sells-stake-in-hawaiis-ala-moana.html

- “Message from the Chair,” Hawaii 2050 Sustainability Plan, January 2008. https://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/op/sustainability/hawaii_2050_plan_final.pdf

About the Author

Working in Hawaii, New York, and the Bay Area, Alison Chiu’s experience in forensic investigations of the building envelope and technical archival research combine two passions to develop a holistic approach to preservation planning. As an Associate at Fung Associates, Inc., Alison engages with clients & owners to provide consultation on historic buildings involving renovation, rehabilitation, and compliance with State and Federal guidelines. Alison is a current Director and past President (2015) of Docomomo US/Hawaii Chapter, and a member of the Association for Preservation Technology International (APTI).

Sunny Spotlight: Modernism in Hawaii is part of the Docomomo US Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home. Previous spotlights include Chicago, Mississippi, Midland, MI, Houston, Las Vegas, Colorado, Kansas, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, South Dakota, Vermont, and Albuquerque. View all Regional Spotlights here.

Have a region you'd like to see highlighted? Submit an article.

If you are enjoying this series, consider supporting Docomomo US as a member or make a donation so we can continue to bring you quality content and programming focused on modernism.

Sunny Spotlight Part Three

Ala Moana Center Re-rearranged