The current architectural exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980, plays a critical preservation role by gathering images of significant modern buildings that need to be known for their contribution to the development of Latin America. However, in Mexico many modern buildings have been neglected for years or no longer exist. The question, then, is: what is the future of modern architecture in Mexico?

MoMA's recently inaugurated the exhibition features photographs, drawings and videos of individual buildings and urban facilities that emerged as a response to political, economic and cultural changes in Latin America during the second half of the twentieth century. Some of the images featured correspond to works that were carried out, while others show projects that were left on paper. Several photographs have another purpose: to preserve the memory of buildings that either no longer exist, that still stand but are in deteriorated condition, or that have been threatened with demolition.

Preservation and the Future of Modern Architecture in Mexico and Beyond

Author

Angélica Martinez Sulvaran

Affiliation

Docomomo US/Oregon

Tags

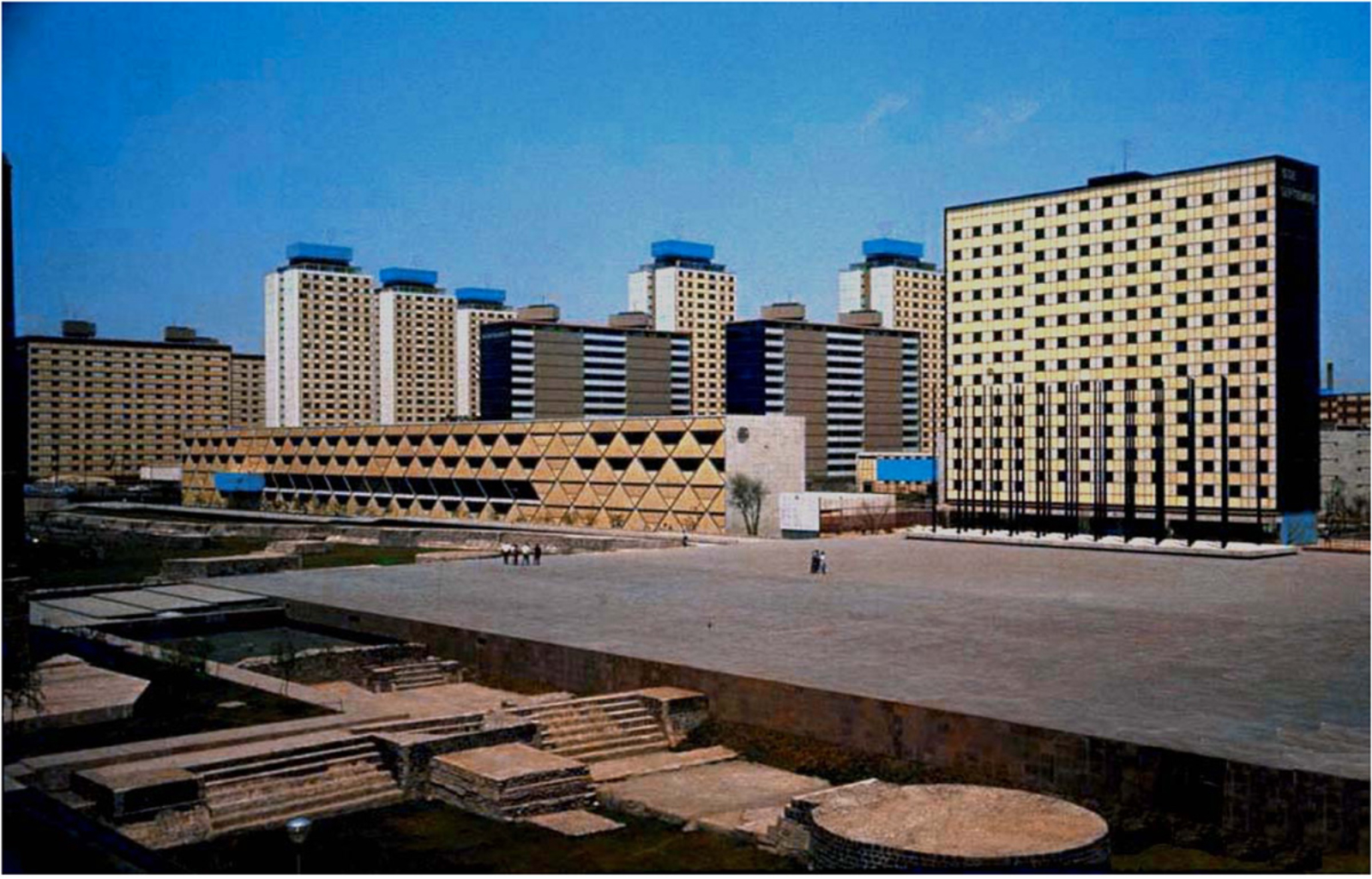

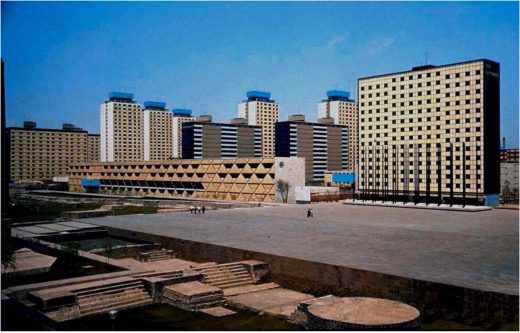

By far one of the most well known large-scale modern housing projects constructed in Mexico in the 1960s is the Conjunto Urbano Nonoalco-Tlatelolco (Fig.1), which was planned to supply the increasing housing demand caused by the migration of rural population to the largest Mexican urban and industrial area: Mexico City. Designed to offer affordable housing for middle-class families, the complex consisted of 102 high-density multi-family towers in a park-like setting. The project also includes schools, recreational centers and day-care facilities.

Designed by Mario Pani, a prolific architect in charge of many architectural projects that transformed the urban landscape in Mexico City, Nonoalco-Tlatelolco represents the materialization of the modern utopia, inspired by Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin from 1925. However, the utopia turned into a dystopia in later years. On October 2, 1968, thousand of students who gathered in the open spaces of the complex to protest against the regime were assassinated. On September 19, 1985, an earthquake shook Mexico City, destroying one of the largest multi-family buildings of the complex and affecting at least eight towers that years later would be demolished. Today most of the buildings that remain in this controversial urban complex are either abandoned, neglected or in danger of collapsing (Fig. 2).

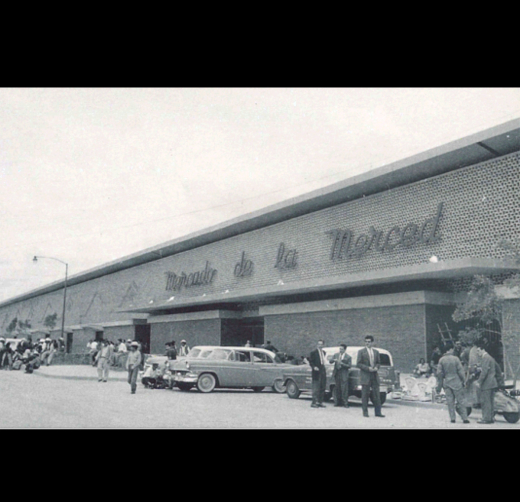

Another modern Mexico building featured in the exhibition is the Mercado La Merced, located in Mexico City and designed by Enrique del Moral in 1957. In the 1950s, the construction of infrastructure and facilities in urban areas was a priority for the Mexican government in order to demonstrate the economic growth and prosperity of the country. At the same time, a generation of architects committed to society's social needs and seeking architectural innovation was emerging. Mercado La Merced is, then, the result of governmental achievements and the dedication of an architect who learned how to adapt functionalist ideas to the Mexican traditions; the market has been the quintessential commercial gathering place since the Aztec civilization dominated the current Mexican territory.

The building still maintains its commercial function; the facility is today the biggest market in Mexico City, not to mention one of the most significant landmarks in the city. Unfortunately in the last three years at least two fires, one in 2013 and a second in 2014, have threatened the integrity of the building, especially the main façade, main hall, not to mention the economy of hundreds of tenants. Partial demolition work started in 2014 and at the time of this writing, the building was still under reconstruction [Note: in December of 2019, the market suffered yet another fire]. Plans have been proposed from private investors and the local government to rehabilitate the area surrounding the market, but the tenants have rejected them because these plans do not consider their housing, recreational and commercial needs.

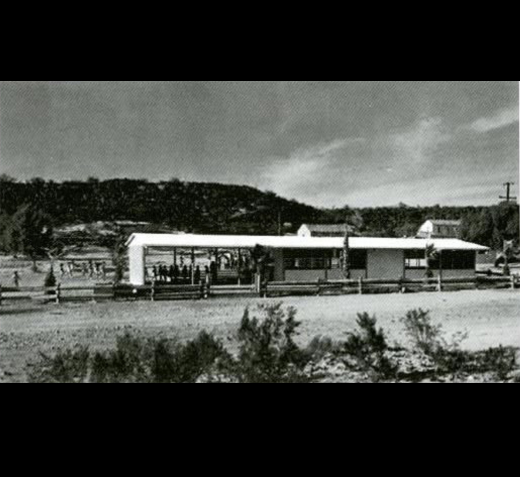

Regarding educational needs, the exhibition displays an important project often disregarded or forgotten: The Aula Casa Rural Mexico (Rural Schoolhouse Project) developed by Pedro Ramirez Vazquez in the 1960s. The project responded to the urgent need of providing educational infrastructure to address low literacy rates among the indigenous population. Ramirez Vazquez, who strongly believed in architecture as a tool to generate a social revolution, devised a model for a school that could be easy to transport, build and adapt according to the weather conditions in different regions of the country. Once implemented, the project resulted in the construction of more than 35,000 rural schools throughout Mexico, contributing to the development of the modern State. It is possible that many of these schools have been demolished in recently years. It would be necessary to develop a research project to survey the remaining structures for which there is not documentation yet to know for certain.

The cases presented reveal the importance of architectural exhibitions and their role as preservation tools. Photographs document the appearance of sites that no longer exist or have been altered. The examples of modernism in Mexico featured in the exhibition are mostly buildings that have survived the wrecking ball, but there are hundreds of modern structures, such as Vladimir Kaspé’s Superservicio Lomas (Fig. 6) or the Manacar building (Fig. 7) that have not. Architectural images remind us of their significance for both collective memory and our individual memories. For example, despite the fact that Nonoalco-Tlatelolco has often been surrounded by negative connotations because of the events that have occurred there, the site is part of the collective memory of the entire nation. Photographs of the site are a reminder for Mexicans that the legacy of the students from 1968 is still alive. They are also a reminder that it is possible to recover after natural disasters, just as the survivors of the 1985 earthquake did.

By acknowledging the importance of modern architecture in the development of Latin American countries, Latin America in Construction raises a series of questions: What are the current conditions of these buildings? What is their future? Why is this architecture not considered valuable today? In the case of the Rural Schoolhouses Project, the question goes beyond the preservation of the buildings themselves: how can modern concepts oriented to develop socially responsible architecture be preserved? Can these concepts be preserved today?

These questions are not only for Mexico or Latin America, but for any city and its people where the legacy of the Modern Movement is present.

About the author

Angélica Martinez Sulvaran is a Historic Preservation graduate from Pratt Institute. She currently lives in Portland, OR, where she serves as a Board member of the Oregon Chapter of Docomomo US.

Sources

Adriá, M. (2015, March 30). Mario Pani y la vivienda colectiva. In Arquine. Retrieved from http://www.arquine.com/pani-y-la-vivienda-colectiva/

Bergdoll, B., Comas, C. E., Liernur, J. F., Del, R. P., & Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.). (2015). Latin America in construction: Architecture 1955-1980.

Hernández, A. (2013, April 16). Cultura en destrucción. In Arquine. Retrieved from http://www.arquine.com/cultura-en-destruccion/