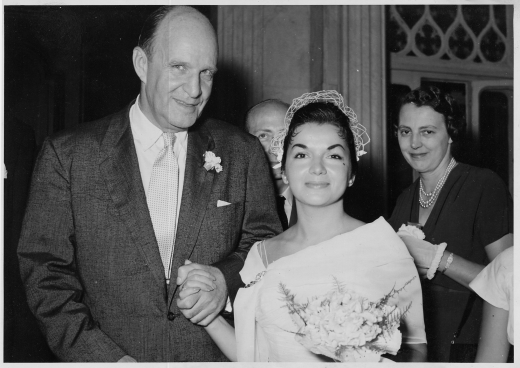

Unfortunately, Father’s restiveness extended to his marriage and family. After ten years of marriage he became dissatisfied with my mother. She was glamorous but aloof. He began to have surreptitious affairs. Mother too was dissatisfied. Father was twenty-three years her senior and held a traditional view of a woman’s role in a marriage. The relationship was too confining for her. Ultimately, their mutual infidelities destroyed the relationship, and an ugly and very public divorce ensued, replete with garish front-page headlines in the New York Daily News. My sister Francesca and I were caught in the midst of a vindictive tug-of-war between two antagonistic and irrational parents. To this day, the divorce ranks as the central formative event in my life. Their graceless split served as a vivid demonstration of exactly how not to divorce.

But there were positive elements as well. Most influentially, my parents instilled in me the importance of achievement, particularly in the artistic realm. Moreover, they diminished the importance of wealth and its accumulation. Father would often remark that the postman made more money than the architect. Of course in his case, for the man described by Business Week as having one billion dollars of work on his drafting boards in 1968, this was not entirely true. But the primacy of aesthetic achievement over financial success was indelibly ingrained in me.

Because of this ancestral predisposition, shortly after Father’s death in 1978, I entered Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design as a Master’s candidate in architecture. I have been a practicing architect ever since. At Father’s memorial service his first wife, Orlean, who had suffered through Father’s alcoholism and depression-era financial misfortune, cautioned me, “Don’t think that it will be so easy.” Of course she was right. Success in architecture requires talent, hard work, good fortune, salesmanship, perseverance and mental toughness. To have done anything else would have been to deny my native skills, knowledge and legacy.

Almost inevitably, I find myself drawn to architectural solutions that Father would have favored. Both of us seek to make complex projects seem simple, with a clarity of circulation, an orderly and uplifting sequence of spaces, an appearance of stability and rationality and a balanced exterior composition. Father was known as a formalist, and I too describe my work in that fashion. Much like the ancient temples that Father sketched as a young man and sought to recapture later in his career, we both believe that architecture should be a transcendent refuge from the vicissitudes and chaos of contemporary life.

About the Author

Hicks Stone is a New York City area architect and principal of Stone Architecture, LLC. He founded his firm in 1991 after working as a senior designer in the office of Philip Johnson and John Burgee Architects. Stone received his Master’s of Architecture from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. He has a national practice with projects from Maine to Florida and the Bahamas to California. His work has been published in Interior Design, House & Garden, Palm Beach Cottages & Gardens, Maine Home + Design and This Old House Magazine. His firm’s principal focus is on the design of luxury residences, retail boutiques and cultural facilities. He has written a biography of his father, Edward Durell Stone, for Rizzoli International Publications. His book, Edward Durell Stone: A Son’s Untold Story of a Legendary Architect, was published in 2011. He has given lectures on his father’s life and work to audiences all over the country.