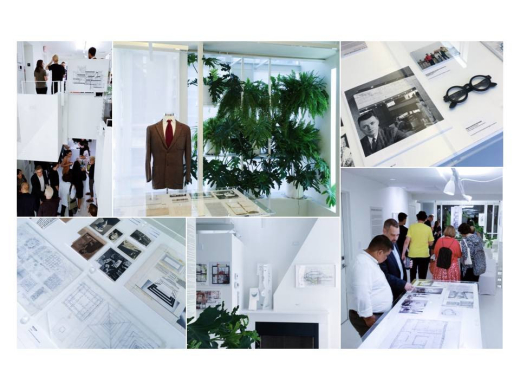

In celebration of Paul Rudolph's centennial earlier this week, Liz Waytkus sat down with Kelvin Dickinson, president of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation and Eduardo Alfonso, Exhibition Coordinator of Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory now on view at the Modulightor Building in New York City.

Tell me about the process that went into this first exhibition.

The first step in organizing the exhibition was to take stock of the items in the PRHF’s archive. As if often the case with an architect's archive, many of the drawings had not been intended as finished products and they were not inventoried during Paul Rudolph’s lifetime. Sorting that out was our first priority, and much of the narrative for the exhibition came about by following the narrative threads found in Rudolph’s office correspondences from the archive.Paul Rudolph’s virtuosity as a draftsmen was incredible: He could articulate a project well enough for his talented employees on letter sized sheets done on the fold-out tray table of a jetliner on its way to Singapore. A lot of those had to do with instructions for employees to adjust something in his home at 23 Beekman Place or at the Modulightor Building, amidst marching orders on how to detail an important aspect of the large commissions he was working on in Southeast Asia. It was obvious that Paul felt an intense connection to his homes, and that he saw 31 High Street, 23 Beekman Place and Modulightor as exemplars that he could build on his own terms and in turn use them as didactic places through which to explain his architecture. He wasn’t the type of architect that suggested linoleum and plastic for clients, but lived in a marble and travertine hall. If he found something new that he was willing to build for a client, he tried it out at home (or in his office) first, and backed up his cavalier attitude to conventional domestic architecture with his own experience. The role the houses and Modulightor played in the overall story of his career became an important aspect that we were wanted to share , and best of all we have the beautiful Duplex one floor below the exhibition, so we get to do what Paul did and say, “Hey look the proof is in the experience of the real thing!”

My understanding is that Paul was a very private individual. How do you think Paul would react to sharing the thoughts behind those designs, which were meant to be private?

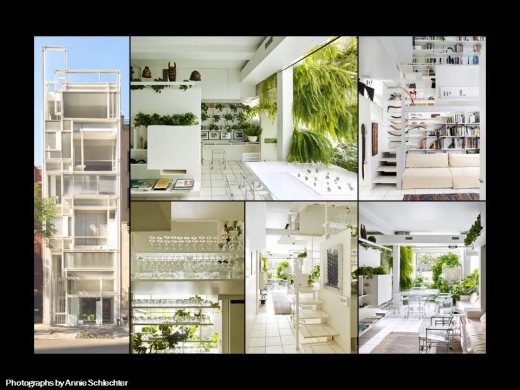

When he was teaching at Yale, Rudolph was careful not to push his students to design their own work as copies of what he was doing. Instead, he focused on teaching a process by which an individual could reach their own conclusions. It is that reservation - that he didn't want to create an army of 'mini-me's - that made him such a great teacher but also difficult to preserve as many of his students went on to become 'starchitects'. Rudolph also never considered his drawings as precious, but simply as a means to an end, which was a building and the experience of being in it. Renderings were to sell the design to the client, and his drawings were often very rough to get the design intent on paper for the people in his office to interpret for working drawings. It is the spirit of the thought process which is captured in the drawings that makes them valuable. In his drawings for Modulightor you can see his early design was very methodical whereas the built facade is far more spatially complex. It is in the original drawings that you see the original intent - the seed of an idea - that later developed into the final work after Rudolph continued to experiment and add new layers of meaning.

What things did you find or ideas did you discover that were a surprise to you?

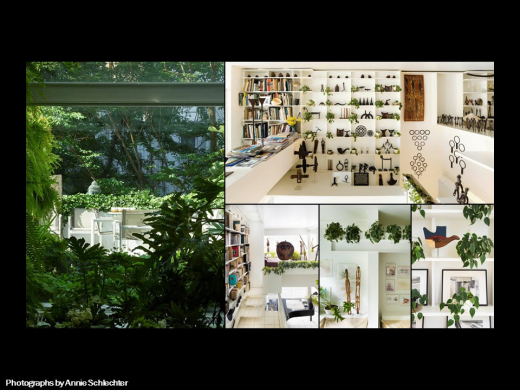

Because of his association with the nebulous term Brutalism, Rudolph get’s unfairly labeled as an ascetic architect, in love with sparsity of unadorned concrete—that could not be further from the truth. Paul Rudolph saw ornament as an essential aspect of architecture and I think his home at 23 Beekman Place is one of the great essay in how to adapt ornament to the technological and social goals of the Modern Movement. In addition to richness that properly scaled ornament can bring to architecture, Rudolph also explored fountains and landscape as essential aspects of architecture. The exhibition opened my eyes to the omnipresence of greenery in Paul Rudolph’s architecture and his commitment to bringing the fullness of life and nature to our modern landscape (a shocking for those that know him only via his Lomex Project).

For someone who knows Paul's work but has not been to Modulightor, what do you think would surprise a first time visitor?

The biggest surprise would be that the building is not built of concrete. During tours people have come up and said they were surprised it was airy and full of light, to which I explain Rudolph had different ways of using materials. In the case of Modulightor, Rudolph used steel i-beams with infill glass panels on the facade - varying the depth of the steel sections to provide scale. If you didn't know Frank Loyd Wright, you would never think the Robie residence and the Guggenheim could have been designed by the same person until you understand the thinking behind them. Like Wright, Rudolph was consistent in his ways of expressing and manipulating scale, space and form even though the materials could be very different between projects. That is ultimately what makes a trip to Modulightor so special for those that only know of Rudolph's work in concrete.

People who visit the exhibition and Modulightor will find not only a complex structure, but one full of Paul's things. What is the story behind those objects?

An aspect that all the objects share in common is their individual and idiosyncratic display within one of Paul Rudolph’s homes; each item has a story that relates it to Paul Rudolph’s travels and another that relates to its own history as an artifact. The objet’s d’art, curious, and tchotchkes are enshrined on pedestals specifically designed by Rudolph and were set within his homes in pivotal spaces that suspend the objects in a very compelling and emotional way—the Equestrian sculpture and Louis Sullivan’s panel in 23 Beekman Place are great examples of this.

While each specific object has a story what’s most interesting is seeing the complex relationships that Paul Rudolph created between ancient artifacts and modern materials such as plexiglas and compact lighting. One of the most interesting aspects of Paul Rudolph’s architecture is his focus on urbanism as an essential aspect of architecture, that when done wall can resolve the collision of historical and contemporary buildings. Undoubtedly, these tests at a small scale informed that focus on urbanism. It’s one example of many architectural experiments that Paul Rudolph used his homes for.

Exhibition Details

Paul Rudolph: The Personal Laboratory

October 4 - December 15, 2018

Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation at the Modulightor Building

246 East 58th Street

New York, NY 10022