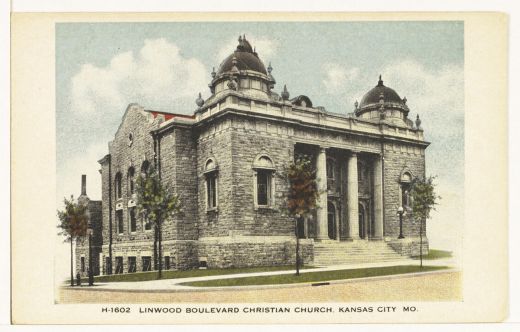

On Halloween night in 1939, the Community Christian Church – at the time known as the Linwood Boulevard Christian Church – suffered a fire that destroyed the church’s second building, and forced them to relocate for a fourth time since the congregation’s inception in 1888.

An Architect’s Disdain, A Community’s Beacon: Wright’s Community Christian Church

Author

Jenny Morrill

Tags

The Church commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design their new home during an unstable time at both the local and global stage. At home, Kansas City was under the control of T. J. Pendergast, a corrupt political boss, while the United States was informally involved in WWII by rationing and supplying materials to the European Allies. The Community Christian Church is one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s lesser known projects, if it is recognized as one at all. Like many places of worship throughout the country, the church faces issues with prolonged building deterioration, whether due to financial challenges, lack of support, resources, or deferred maintenance and repairs that get exponentially worse with time. However, this is not due to a lack of visibility or purpose within the community. While there is little information provided within Frank Lloyd Wright’s extensive body of work, there is no lack of information and documentation by local experts. This is mainly due to Wright’s original design intent and vision for the “Church of the Future” differing from the designed reality – making it, in his eyes, an indignity in his career.

During November of 1939, Frank Lloyd Wright and his Taliesin Fellowship had little work going on at the time. There were only a couple Usonian houses in design outside of the Johnson Wax Building and Herbert Johnson house wrapping up construction in Racine, WI. Both the Church and Wright and his team were excited to take on the project and had high hopes for the finished design. Wright intended the new Community Christian Church to be the “Church of the Future” with an architect’s vision of a modern, innovative design.

Curtis Besinger, one of Wright’s apprentices in the Fellowship at the time and later Professor of Architecture at the University of Kansas, wrote:

To me this seemed like a wonderful opportunity. There had been several public buildings, designed in the ‘moderne’ style, constructed in the city. But, Kansas City was conservative and traditional architecturally as well as in other ways. I hoped that the new building for Community Church might be the kind of landmark in Mr. Wright’s career that Unity Temple had been, and that it would give Kansas City an example of what a good, modern building might be. [1]

Even before the design began, challenges and constraints appeared when the project’s available budget drastically differed from the actual project estimates. Wright estimated, to completely meet and fulfill the programmatic and functional requirements for the Community Christian Church, the project would be around $500,000. The initial fundraising goal for the project was $150,000, but the Church was able to raise about $100,000. In April of 1940, with the hope that more funds would become available once work began and the community recognized their efforts, Wright signed a formal contract for the project. The expectation was that construction would kick off a month later in May and finish by that winter. Yet, it was months later when the Church bought the property off Main Street as the site for the new building, that design and documentation began.

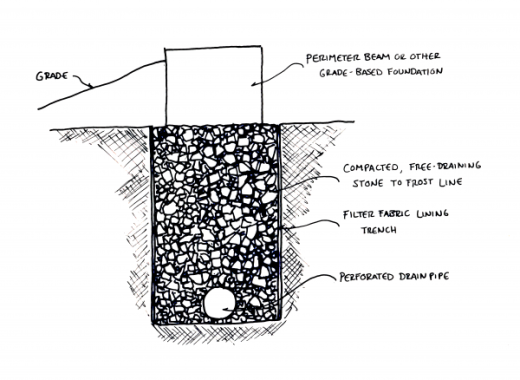

Wright’s original idea for the church was a light, steel frame superstructure, coated in a thin layer of gunite, that would sit on a flexible, "floating," rock ballast foundation. This foundation, also referred to as a rubble trench foundation, consisted of a poured concrete slab, with or without grade beams, situated on top of pounded rock trenches.

The steel structure was to utilize as few columns to support the floor and roof as required. The steel bar joists in the floor were spaced farther apart than normally expected with the type of construction. With the inherently flexible nature of the “floating” foundation system, the steel structure needed to respond in kind with its own flexibility to prevent cracking, or worse, system failure due to an unharmonious design. Wright was well-experienced with the system and utilized rock ballast foundations in his previous projects without issue, including the Johnson Wax Building. However, this was Wright’s first use of gunite, a technique where dry concrete mix combines with water at the end of a hose and is sprayed through the nozzle at high velocity onto a substrate.

He proposed the skeletal, steel frame be covered with layers of heavy paper encased in steel mesh and strung with steel wires tied back to the structure. The gunite would cover every surface, both inside and out. The design would be elegantly simplistic and lightweight, but not without ingenuity.

During the brief period of construction documentation, design changes were made and ideas reworked due to internal and external forces influencing the project. Wright originally intended for a thin, projecting copper fascia along the roof edge, and stamped, perforated copper sheets, reminiscent of the perforated wood screens at various Usonian houses, to cover the exterior glazing. The ornamental pattern in the dome above the chancel and central skylight were also intended to be made from copper. With the rationing of metals due to the war, these details had to be removed.

The City’s Building Commissioner at the time was, as Wright called, a “good ‘old foundation man’” who would not approve the permit unless the foundation was the typical, solid concrete foundation used everywhere else in Kansas City. Without Wright’s knowledge or approval, the commissioner and building committee lawyers hired a local engineer to change the design to solid concrete foundations and footings.[2]

Wright stated: “I should have stopped the building where it was and have withdrawn from any connection with it whatever. The building was, henceforth, in the hands of the enemy. The fundamental condition of success of a rational experiment in behalf of the church was gone… The building was soon no longer mine except in shape – the shape which had already lost some of its meaning.”[2]

Yet, Wright stayed on the project to remedy what he could, knowing there would be issues in the future with cracking now that a flexible structure sat atop a rigid foundation. But that, too, was altered during construction by the commissioner and engineer. More bracing and supports were added so that it was “strengthened” and “made safe,” making the frame rigid in areas where Wright needed it to remain flexible.[2] By this point, even though Wright was still the architect of record and remained on the project until the end, he had been socially and politically denied as architect. The City’s commissioners and lawyers no longer involved Wright in discussions for the project and only dealt with the Church and the construction manager, Ben Wilstcheck, who was Wright’s contractor on the Johnson Wax building and Johnson residence. With the lack of Wright’s presence on the project, additional concessions were made during construction. The parking terraces, which had been Wright’s strategy for addressing the site’s constraints, were not included in the end. The interior finishes, furniture, and landscaping detailed out by Wright and his Fellowship apprentices were also cut out. The Steeple of Light, another key design element in Wright’s vision, was postponed indefinitely until it could be constructed at a later date when the materials and technology were available. Community Christian Church finished construction in winter of 1942. On the day of the opening ceremony, another critical issue became apparent. Wright’s design included pipe coils under the flooring that would circulate hot water to serve as the building’s main heating system. However, the pumps had been installed incorrectly, so the whole system did not function as designed.

Besinger visited the building shortly after it was completed, calling it “a great disappointment; it looked raw and unfinished… This was a building that did not receive Mr. Wright’s finishing touch – the finishing touches were added by others…”[1] Only a couple years after the building’s completion began a consistent series of improvements, additions, and alterations have been made to the Community Christian Church. These changes have ranged from simple refinishes to larger, programmatic interventions. Given Wright’s estimates to provide the Church with everything they needed to function versus the final project budget, the long history of improvements to the Community Christian Church is not surprising. In 1944, Kansas City architect, Herbert E. Duncan, designed the addition now known as Bonfils Chapel. In 1947 and 1950, another architect designed a different addition which was later expanded to form the current Centennial Hall. In 1994, the Steeple of Light was finally completed with the addition of a perforated, gunite dome from which four light cannons project into the night sky.

In a 2022 Historic Structure Report conducted by STRATA Architecture + Preservation detailing the history and current status of the Church, this extensive list of improvements and changes were “all for the purposes of ensuring the building could continue to function as it was originally intended – the home of Community Christian Church.”

Not only has the church continued to serve its purpose since it was completed in 1942, but it has ingrained itself within the larger Kansas City community. The Community Christian Church lacks neither purpose nor visibility – both literal and figurative – within the community that would typically hinder it from maintaining relevance in today’s society. A congregation that originally served as a small Sunday school now encompasses individuals from eight different counties across both Kansas and Missouri. As the Church expanded, “[t]o reflect the idea that the church is ‘everybody’s church’ and ‘to emphasize protests against closed membership, closed communion, closed anything and everything’, Linwood Boulevard Christian Church changed its name to Community Christian Church in 1930.”[3]

Historically, and consistently, the Church has served the larger Kansas City community beyond offering religious services. It has expanded its reach to serve a more universal purpose, providing support and resources for local community services, such as food pantries and aid for the homeless, and offering its space to host community events, local artists’ work, social justice programs, political discussions, etc.[4]

However, the Community Christian Church currently struggles in this programmatic grey area of being more than just a church, but not quite able to serve as a true community center due to the limitations of its architecture. Multiple building analyses have been conducted over the years to identify the main issues that the Church currently faces. At the beginning of every service, Reverend Shanna Steitz welcomes people of “all ages, all abilities, and all identities” into their community. However, the Church struggles with the non-ADA-compliant spaces Wright designed, which are now far too small and lack the proper programmatic support and infrastructure to allow the Church to expand its purpose within the larger community while still faithfully and effectively supporting its congregation.

Unfortunately, Wright’s lack of acknowledgement forfeited the church’s broader prominence as a Frank Lloyd Wright project, and subsequently, all the benefits that come with that recognition. Before the project was completed, Wright claimed once “the messing around is over, we go down there ourselves to take what will be left of the whited sepulchre and make it what it was intended to be before it went all-out ‘legal.’”[2] However, the building “has never appeared as an illustration in any publication on Mr. Wright’s work for which he selected the illustrations.”[1]

As Besinger states: "It was and is a building that suffered as a result of Mr. Wright’s not seeing it through to the finish. The building as it stands today is something of an anomaly. Mr. Wright rejected it. Kansas City has accepted it."[1]

Though, Wright’s experience with this project is not one unfamiliar to many architects today. Similar to many projects to this day, the Community Christian Church is not unique in the way it was the victim of a series of compounding factors and decisions that created the final outcome. Warring goals and interests, divided attention, political power dynamics, bureaucracy – what is, in total essence, the politics within the professional realm of architecture. No matter how it is managed and navigated, it is always the design, and consequently the occupant, that suffers the most in the end. While the project was subjected to value-engineering during construction, another experience familiar to many architects and projects today, it was only the rock ballast foundation and steel structure that was altered without Wright’s knowledge and permission.

In an identity conundrum similar to Theseus’ Paradox, the Community Christian Church has had to fight over fifty years-worth of narrative claiming that it is not a Frank Lloyd Wright building because of this. Regardless of Wright’s attitude towards the project, he stayed on the project until the end and is the church’s architect of record. Wright intended the new Community Christian Church to be the “Church of the Future” with an architect’s vision of a modern, innovative design, yet the Community Christian Church has fulfilled Wright’s vision in its own way – one that seeks to transform and facilitate love, justice, and mercy within the community.

Citations

[1] Besinger, Curtis. 1995. Working with Mr. Wright: What It Was Like. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press.

[2] Wright, Frank Lloyd. 1943. Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography. Second edition. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

[3] STRATA Architecture + Preservation. 2022. Community Christian Church Historic Structure Report.

[4] “Justice and Mercy,” Community Christian Church.

About the Author

Jenny Morrill is a Kansas City native, and architectural designer, researcher, and writer. Jenny holds an M. Arch from Kansas State University and currently works at DRAW architecture + urban design. Her interests and research are captivated by adaptive reuse, and continues to lead her in pursuit of further expertise in the subject. She will be joining the Rhode Island School of Design graduate Adaptive Reuse program starting fall 2025. Jenny is a member and leader of HouseKC, a local Kansas City coalition which seeks to end homelessness in the metropolitan area by advocating for long-term solutions.