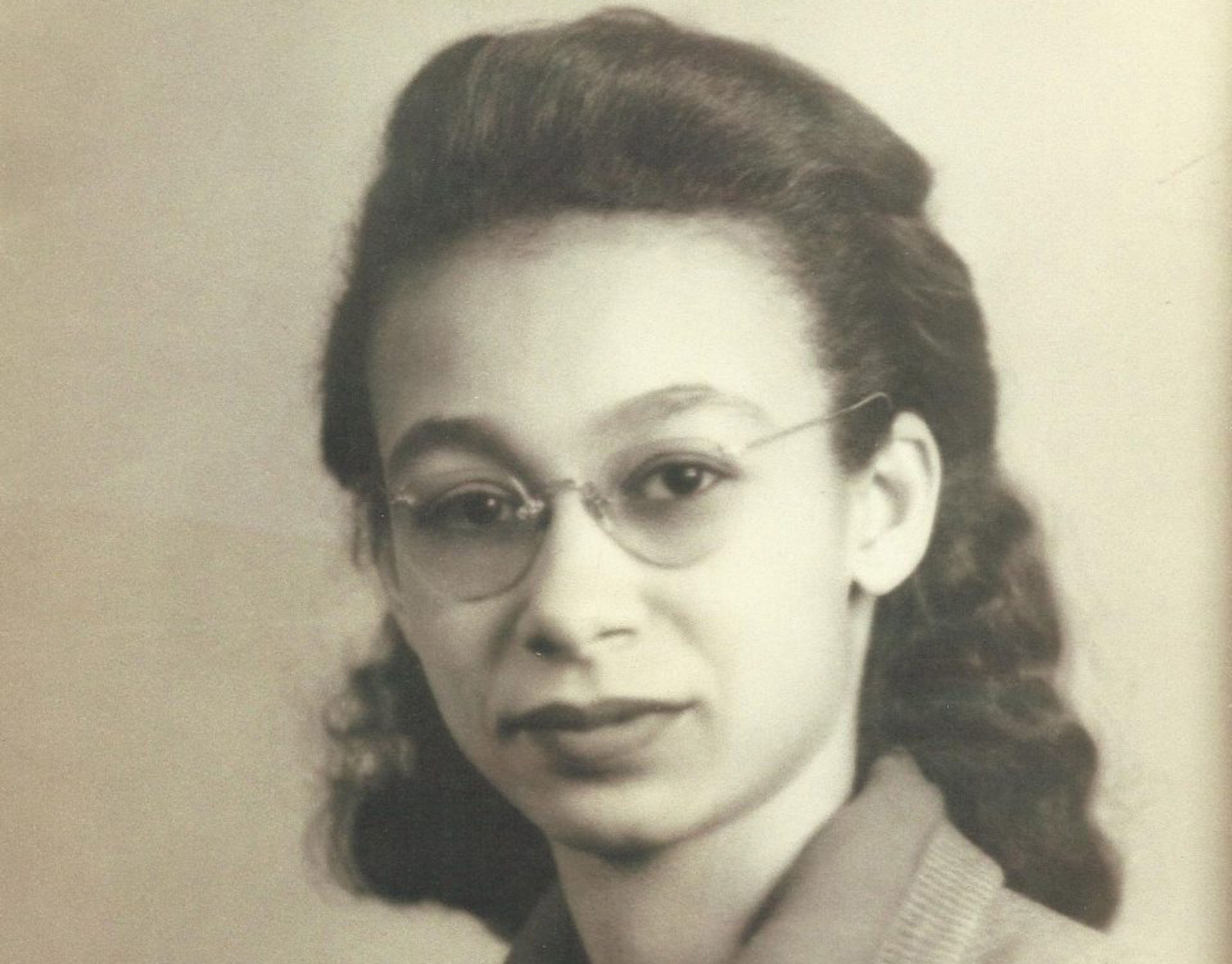

Georgia Louise Harris Brown

Architect

12 June 1918(Birth)

21 September 1999(Death)

Biography

Georgia Louise Harris Brown was born in Topeka, Kansas, on June 12, 1918. Her family’s genealogy of strong women of mixed ancestry included former enslaved African Americans who arrived from the South to the Union’s slavery-free state after 1861, Native Americans, and German settlers.

The daughter of Carl Collins Harris and Georgia Louise Watkins Harris, the future architect was part of a middle-class family with four other siblings, all of whom would become university graduates. From an early age, she exhibited an interest in drawing and painting, as well as working on cars and farm equipment with her brother Bryant. After graduating from Seaman High School in North Topeka, where she distinguished herself as one of the top students, she attended her mother’s alma mater, Washburn University, from 1936 to 1938. Soon after graduating, Brown went to Chicago to visit her brother, where she attended a summer course with Mies van der Rohe at the Armour Institute of Technology and took flying classes from one of the female pilots at a black aviation club, pursuing a passion that continued throughout her life.

In the fall of 1938, Brown enrolled in the School of Engineering and Architecture at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. Since the early 1930s, the architecture school had embraced a modernist agenda that advocated a unity of art and technology, with studies linking industrial production and professional practice. The program placed a strong emphasis on building processes and techniques, concerns that would be reflected in Harris Brown's later practice.

In 1940, she interrupted her studies and, in 1941, married James A. Brown, a roommate of one of her brothers in Chicago and an electrical contractor. By the summer of 1942, she was taking evening classes at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). She attended classes taught by Mies and later described her contacts with him as some of the most interesting times of her life. In June 1944, she received a bachelor of science in architecture degree from the University of Kansas. Although the number of women in the architecture schools had increased during World War II, her university years were not without reminders of racism and sexism; later, she recalled being asked several times by one professor if she didn’t think she should be in home economics instead of architecture.

In 1945, she began working in the office of black architect and structural engineer Kenneth Roderick O’Neal. It was probably at O’Neal’s that Brown became acquainted with other young black professionals (including Beverly Lorraine Greene and John Moutoussamy) who, like her, were struggling for a place in a racist society. She worked with O’Neal until 1949, when she became a licensed architect in Illinois. That same year, she moved to the offices of Frank J. Kornacker Associates, Inc., where between 1949 and 1953 she was the only professional woman. While at Kornacker Associates, she designed residences and additions to factories, and an office and auditorium building, while developing structural calculations for reinforced steel and concrete buildings, which included Mies’s Promontory and 860 Lake Shore Drive apartment buildings. In her CV, Brown stated that she was responsible for structural calculations for other projects designed by Mies associates, such as the Lunt Lake Apartments by Holsman, Holsman, Elekamp and Taylor Architects; the East Dentistry, Medicine Pharmacy Building at the University of Illinois, the urban renewal plans for Babbit, Michigan, and the Fayette County Hospital in Vandalia, Illinois, by Pace Associates, Architects; as well as other projects such as the Prairie Court Apartments by Keck and Keck, and the Glencoe Supermarket by Sidney Morris and Associates.

Since 1945, she had also been moonlighting with Woodrow B. Dolphin, who was working for the Federal Public Works Agency. During this time, she became one of the first black members of the Chicago chapter of Alpha Alpha Gamma, the professional association that in 1948 would be renamed the Association of Women in Architecture.

In 1952, unable to reconcile her career and marriage, she divorced and sent her two children, James and Georgia Louise, to live with her parents in Topeka. This period of her life was also a time of reflection about her future. Brown was acutely aware that opportunities for advancement were limited by her race and gender. Around this same time, Brown met the progressive academic Maria Luisa Barros, who invited her to visit Brazil. After her visit she decided to move to Brazil. She did so in 1953, and by 1954 she received a permanent residency visa. However, it took until 1970 for her diploma to be validated and for her work license to be issued. Meanwhile, she designed and did structural calculations for the office of American-born Charles Bosworth, a former associate of the American designer Raymond Loewy and Associates, where one of her first projects was likely the National City Bank Building in the heart of São Paulo. During this time she also collaborated with Racz Construtora on many works, including the Kodak film plant at the city of São Jose dos Campos (1969–1971) and the Trorion S/A, a foam and mattresses plant (1963–1965).

She also worked on many private residential projects, which were sometimes developed in partnership with associate designers such as Julian D’Este Penrose and Karl Hans Adolf Wiechman. After obtaining her Brazilian architecture license in 1970, Brown worked increasingly with private investors and real estate developers who were planning and operating new condominium residential areas in the city. Although she preferred to work alone, she often had a Brazilian male partner. She founded the firm Brown Bottene Construtora Ltda, followed by Gryphus Arquitetura Ltda, which lasted until 1993, when illness forced her retirement and return to the United States.

An analysis of her many residential projects may uncover some characteristics of what might be called a “feminine approach to design,” following Karen A. Franck’s concept of connectedness and inclusiveness and a sense of complexity and flexibility. When designing, especially residences, Brown always established a close relationship with her clients, listening carefully and trying to understand the family’s daily patterns and everyday experiences, which she then reenvisioned in her projects with great attention to spatial and visual connections in order to create a sense of spatial continuity.

In a letter sent from Brazil in the mid-1980s, Brown asserted that she never thought of herself as having been a black pioneer female architect, but simply an architect. Later in life she moved to Washington DC to be closer to family. She died in 1999 following surgery for cancer at the age of 81.

Excerpted and adapated from the Beverly Willis Pioneering Women in Architecture databse.