During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Mexico experienced several social and political transformations. As a nation transitioning from a dictatorship to a democratic state, Mexico needed to find an identity as a modern and liberal country. The economic and political reconstruction materialized through the arts and architecture, and these transformations were most evident in Mexico City; it was not only the capital of the country but also its creative hub. It was here that American artist Marion Greenwood’s murals and artwork contributed to one of the first projects that would embody post-revolutionary ideals: the Abelardo Rodriguez Market.

Marion Greenwood: A Modern Woman in Modern Mexico

Author

Angelica Martinez-Sulvaran

Affiliation

Docomomo US/Oregon

Tags

Arrival in Mexico

In an interview conducted by Dorothy Seckler in Woodstock, New York in 1964, Marion recounted that her adventure in Mexico began in the early 1930s as she drove from New York to Mexico City. There she met artists Leopoldo Mendez, Alfredo Zalce and Pablo O’Higgins, a former Diego Rivera collaborator.

After spending time experimenting with frescoes in Taxco, Marion returned to Mexico City and was introduced to Ignacio Milan, the rector of the University of San Nicolás Hidalgo, one of the first colleges in the Americas. Greenwood expressed interest in painting frescos on the ancient walls of the university, an idea that the rector immediately accepted. Not only did he allow Marion to paint the walls, but he offered to cover her research, lodging and expenses in the city of Morelia, home of the university.

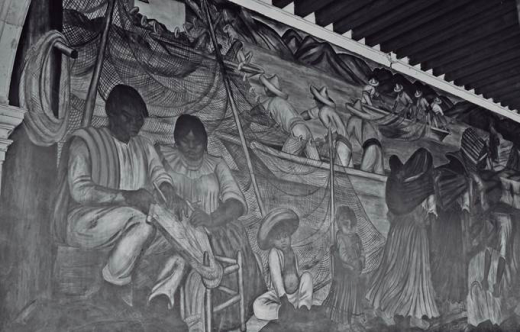

The inspiration behind Marion Greenwood’s work at the University of San Nicolás de Hidalgo was the everyday life of the disadvantaged population. However, since she was invited by the rector to paint frescos, undergraduate students perceived her as just an another painter, distant from the realities of the country. One day Lázaro Cárdenas, who was campaigning for president, stopped by the university, noticed Greenwood’s work, and asked her what the message of the mural was about. With the help of some translators, she explained to the future president of Mexico that she was portraying a scene of the daily life of Tarascan people.(1) Not only was Cárdenas impressed - as he identified himself as a Tarascan - but the students also became fascinated with the mural. As a result of this brief and crucial meeting between Greenwood and Cárdenas, the artist completed Paisaje y economía de Michoacán (Landscape and economy of Michoacán), the mural that adorns the main patio of the university.

Abelardo Rodríguez Market

In the 1930s, only four markets supplied food in Mexico City. This became a serious problem when rural-to-urban migration as a result of the Revolution and lack of job opportunites in the countryside caused a drastic increase to the population. Mexico City’s historic center, the economic and social center of the city, became a home for thousands of migrants coming from rural areas. Therefore, the local government determined that a new market was needed in this area. The land selected to build the market had been occupied by Colegio de los Indios de San Gregorio (Saint Gregory School for Indians) during Spanish Colonial times. After Mexican Independence, the site was transformed and became the Colegio Nacional de Agricultura (National College of Agriculture). Before the construction of the market, the land was owned by the Mexican Army and was used as a daycare center for working-class children.

In 1933, the local government assigned architect Antonio Muñoz to devise the architectural program. The idea was to provide the community with a multifunctional building by adapting the historic construction to different uses and preserving the educational tradition of the site. The resulting project was a civic center that included a market, a daycare center for children and a theater, producing a fascinating building that combines baroque components with art decó and functionalist elements. As the commemorative plaque reads, the market, named after president Abelardo Rodriguez, represented the largest project undertaken to that point for a modern market in Latin America.

The relevance of conceiving a facility of this type in Mexico City's historic center lies on the incorporation of modern concepts in a commercial environment, such as order, organization, and the idea of having a permanent, confined space to buy and sell. Since Prehispanic times, trading used to be performed in temporary outdoor markets called tianguis. During the Spanish Colonial period, commercial traditions were transplanted to new concepts of public space, such as squares and parks, which became sites of intense commercial activity. Although this commercial model is rooted in social and cultural traditions, the garbage produced in the tianguis, usually left in the streets and open areas, became a public health issue since there were no regulations for waste management. The construction of a permanent 3.6-acre market in proximity to significant historic landmarks and designed considering sanitary standards and functionalistic concepts was, therefore, a great achievement that set a precedent for future market projects during the Modern Movement.

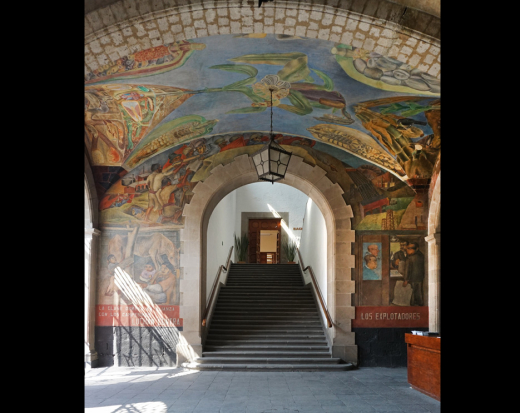

The Murals

The architectural richness of the market is complimented by the murals that cover its interior walls. The incorporation of art inside the building responded to the ideals of contemporary Mexican artists and architects, who strongly believed that art is a powerful tool to educate the masses. Diego Rivera, one of the principal leaders of the incipient Mexican muralist, was designated to execute the murals for the Abelardo Rodríguez Market. Rivera was unable to paint himself because of his heavy workload, but instead supervised a group of students who worked on the commission.

In addition to Rivera, the local government invited another group of artists to participate in the project: the Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (Revolutionary Writers and Artists League). The League had been founded in 1933 by a group of leftist intellectuals to propagate revolutionary ideas through art works and literature. As part of the League, talented national and international artists joined the project, including Pablo O’Higgins, Ramón Alva Guadarrama, Angel Bracho, Pedro Rendón and Isamu Noguchi.

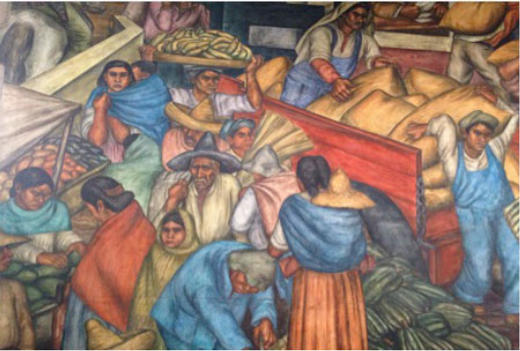

Marion Greenwood was also invited by the local government to participate in the creation of the murals as the recommendation of Diego Rivera and Pablo O’Higgins. As Greenwood would confirm, her paintings were influenced by Mexican Muralists, such as Rivera and Orozco. Nevertheless, the political environment that she found in Mexico, in addition to her social awareness, defined the character of her creations.2 Her work in Mexico reflects the reality of peasants and the working class. The almost three thousand square-feet mural, which she never gave a title, is often called La Industrialización del Campo (The industrialization of the countryside) and is located in the northeast stairway of the market. For this project, Marion collaborated with her sister Grace,3 who painted the opposite stairway. Grace’s frescoes are called La Minería (The mining) and Hombres y Máquinas (Men and machines). Completed in 1935, the murals were a criticism against injustices done to both urban and rural workers by the ruling class in complicity with the federal government.

The legacy of Marion Greenwood

Art curator James Oles, specialist in Modern Mexican Art from 1910 to 1960, described Marion and Grace Greenwood’s murals for the Abelardo Rodríguez market as some of the most important public artworks carried out by American artists anywhere. The artist herself was also able to open her own way as a muralist in an environment dominated by men. In addition, Greenwood and the rest of the artists who collaborated in the project contributed to achieve of one of the first buildings completed under the concept of integración plástica (plastic integration), a movement that sought to integrate muralism and architecture in order to give art function and meaning.

After completing her commission in Mexico, Greenwood moved back to the United States, where she aligned with the social realist movement and continued to work on murals, such as the frescoes in the Red Hook housing project in Brooklyn, New York, and the mural The History of Tennessee, in the student center auditorium of the University of Tennessee. Greenwood passed away on February 20, 1970 at the age of 60.

About

Angélica Martinez is a Historic Preservation graduate from Pratt Institute. She currently lives in Portland, OR, where she serves as a Board member of the Oregon Chapter of Docomomo US.

Notes

1. Ethnic group of Prehispanic origin located in the geographic area of the present-day Mexican state of Michoacán, parts of Jalisco, and Guanajuato.

2. Greenwood eventually would change her mind, as she said that Marxist ideology was “almost rigid idea of propaganda which I think was very bad for all of art at that time because it took the universality out of one's message and instead made it into almost a story-telling kind of thing.”

3. Although Grace Greenwood demonstrated talent and mastering of the fresco technique in the murals she painted in Mexico, she eventually decided not to follow an art career.

Sources

López Orozco, Leticia. "Los murales de las hermanas Grace y Marion Greenwood." Crónicas, 2008, 46-54 http://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/cronicas/article/view/17283/16468.

Oral history interview with Marion Greenwood, 1964 Jan. 31. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-marion-greenwood-11871.